The Mini, the Micro, and the Macro— Finance and its Application in Three Stories

Behavioural Loss Aversion, the Empires of Rockefeller, and Market Collapse from Tulips to Today

This one is pretty long and dense but stay with me now, it’s gonna make sense, believe that.

Dale.

Behavioural Loss Aversion and Volatility Skew: Overpriced Downside Protection in Treasury Options

(Case Study: See Bill Huang’s Bond Bull)

Investors in options markets have long observed a volatility skew—a systematic mispricing where downside protection trades at a premium relative to symmetric upside bets. A key driver of this asymmetry is behavioral loss aversion: the tendency of market participants to fear losses more than they value equivalent gains. This report explores how loss aversion contributes to volatility skew and the consequent overpricing of downside protection, using the case of leveraged Treasury ETFs—Direxion Daily 20+ Year Treasury Bull 3X (TMF) and Bear 3X (TMV)—to illustrate a tactical opportunity. We examine scholarly insights from behavioral finance (notably Prospect Theory by Kahneman & Tversky) and empirical research on options pricing anomalies (e.g., net-buying pressure), implied volatility surfaces, and the unique dynamics of leveraged ETFs. We then outline a strategy that targets short-dated TMV put options ahead of high-volatility macro events (such as Federal Reserve FOMC meetings) to exploit underpricing driven by skew. Finally, we add a monetary-policy outlook section explaining why a dovish Fed surprise is plausible, strengthening the case. All assertions are backed by academic and industry evidence.

Behavioral Loss Aversion and Prospect Theory

Modern behavioral finance posits that investors are not perfectly rational and often exhibit loss aversion, a core principle of Prospect Theory (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979). Loss aversion implies that “losses loom larger than gains” in investors’ minds: the psychological pain of losing a dollar is about twice as powerful as the pleasure of gaining a dollar of the same size [1]. Kahneman defines loss aversion as “the response to losses is stronger than the response to corresponding gains”, highlighting that people experience a loss more intensely than an equivalent gain [1]. Consequently, individuals will pay a premium for financial insurance that protects them against adverse outcomes.

Zakamulin (2023) shows that “loss aversion alone can explain all stylized facts of implied volatility”, reproducing the familiar smirk-shaped implied volatility curve and creating significant volatility and skewness risk premia, even under normally distributed returns [2]. In plain terms, accounting for investors’ heavier weighting of losses versus gains yields an options market where crash protection (i.e., high-volatility OTM puts) is expensive, embedding a persistent volatility risk premium.

Loss Aversion and Volatility Skew in Options Markets

Option markets provide a clear lens to observe loss aversion. In equity index options, a well-known “smirk” emerges: out-of-the-money (OTM) put options consistently trade at higher implied volatilities (and thus higher prices) than OTM calls. One explanation is that “investors typically fear a sudden fall in stock prices more than a sudden rise” and are “willing to pay more to hedge against a downturn” [3].

Empirical research confirms that loss aversion is a key driver of volatility skew. Bollen & Whaley (2004) find that net buying pressure for put options steepens the implied volatility curve, indicating that high demand for put protection inflates option prices [4]. Garleanu, Pedersen, & Poteshman (2009) similarly attribute persistent option-pricing anomalies—such as skew and term structure—to demand imbalances [5]. Both studies support the idea that investors’ eagerness to insure against losses (downside)—an expression of loss aversion—materially inflates put prices relative to calls, creating a “skewness risk premium.” In other words, sellers of that upside optionality often earn excess returns, while buyers of crash insurance tend to overpay.

Implied Volatility Skew in Treasury Options

The U.S. Treasury market offers another context where volatility skew is shaped by investor behavior. For many institutions, a sharp “yield spike” (rising yields, falling bond prices) is the feared event, much like an equity crash. Thus, ahead of uncertain economic or policy events, traders buy puts on Treasury futures (to hedge against a bond selloff), driving up the implied vol of OTM put options relative to calls.

During the post-2008 quantitative easing (QE) era, when policy rates hovered near zero, this dynamic became pronounced. A CME Group report notes that “from 2009 through 2013, 5- and 10-year Treasury options skewed sharply to the downside (OTM puts cost more than OTM calls),” reflecting fears that QE would end abruptly and send yields higher [6]. Once tapering was signaled in mid-2013, this skew moderated—vindicating the view that “investors were overpaying to hedge against a potential yield spike” [6].

More recently, following Fed tightening in 2022–2023, some strategists argued that markets had begun to fear yields falling (i.e., a dovish pivot), which could invert or flatten the skew. Nonetheless, as of mid-2025, while some anticipation of Fed rate cuts exists, the default fear among many remains a policy misstep that keeps yields elevated or even higher. The result is that OTM options protecting against rising yields (Treasury puts) still trade richer than OTM calls.

Leveraged Treasury ETFs TMF and TMV: Structure and Dynamics

TMF (Direxion Daily 20+ Year Treasury Bull 3× Shares) and TMV (Direxion Daily 20+ Year Treasury Bear 3× Shares) are leveraged ETFs that magnify daily moves of long-dated U.S. Treasuries. TMF seeks to deliver 3× the daily return of the ICE U.S. Treasury 20+ Year Bond Index, while TMV delivers –3× the daily return. Both rebalance daily to maintain this leverage, which introduces path dependency and volatility drag.

Because of daily rebalancing, both TMF and TMV suffer “decay” over time if the underlying index is choppy. Historical performance shows TMV lost ~96% of its value from inception (2009) to mid-2023, and TMF lost ~72% over the same period [7][8]. This paradox—both bull and bear funds losing value—stems from the compounding effect of volatility and rebalancing [7]. Therefore, these ETFs are best used for short-term tactical trades, not long-term holds.

Their options markets are active with speculators and hedgers around macro events, because OTM TMV puts (bullish bond bets) or OTM TMF calls pay off if bonds rally (yields fall), while OTM TMF puts or OTM TMV calls pay off if yields spike (bond crash). Due to the daily reset, TMF and TMV are inverse on a short horizon, though tracking error and path dependency prevent perfect symmetry.

Skewed Demand: Hedging Yield Spikes vs. Yield Drops

In practice, investors frequently hedge against rising yields (bond crashes) by buying TMF puts or TMV calls. This heavy demand elevates the implied vol on those instruments. Conversely, OTM TMV puts (bullish bond bets) and OTM TMF calls see less demand, leaving their implied vol — and hence their prices — comparatively low. The resulting skew typically appears as:

IV(OTM TMF puts) > IV(OTM TMV calls) > IV(OTM TMV puts) > IV(OTM TMF calls).

Ahead of uncertain policy events such as FOMC meetings, fear of a hawkish surprise (leading to a yield spike) often dominates, causing the skew to steepen. Meanwhile, bullish bond scenarios (expectation of rate cuts) remain secondary for most participants, so options that pay off on dovish outcomes remain underpriced.

Monetary Policy Outlook:

(See: The Almighty Jerome, Beyond the Headlines, The Inflationary Battleground)

The Tactical Opportunity: Buying Underpriced TMV Puts Ahead of a Dovish Surprise

Given the behavioral skew driven by loss aversion and strong reasons for a Fed cut, a contrarian strategy can be constructed for traders who anticipate a dovish surprise around the coming FOMC meetings (i.e., yields likely to fall sharply). In such a scenario, the options market may have overpriced protection against a yield spike, while underpricing protection against a yield drop. By buying short-dated TMV puts (bets that TMV will fall if bonds rally) at depressed implied vol, one can capture outsized returns if the Fed’s decision indeed causes yields to plunge. The leverage in TMV magnifies this effect, making small premiums potentially deliver large payoffs.

Implementation Steps

Identify Event & Timing

Target the FOMC meeting.

Enter 2–5 trading days before when implied vol on TMV puts remains low but skew is high.

Verify Skew Differential

Compute Skew Ratio = IV(1-week ATM TMV Put) / IV(1-week ATM TMF Call).

Entry Signal: Skew Ratio < 0.70 (e.g., 28%/43% ≈ 0.65).

Select Strike & Expiration

Expiration: (1-week).

Strike: ATM ($50) for max gamma or slightly OTM ($48) for lower premium. E.g., $48 put costs ~$0.65 (IV ~27%).

Position Sizing

Allocate ≤ 3% of portfolio.

For a $100k portfolio, allocate $2k. If ATM put = $1.00, buy 20 contracts (20×100 = $2,000).

Execute Limit Orders

Confirm ≥ 200 open interest; ensure bid-ask spread ≤ $0.05.

Enter limit orders near midpoint.

Monitoring

Fed-Fund Futures: If implied cut probability jumps > 10% within two days pre-FOMC, consider adding.

Bond Futures Implied Vol: If 10- or 20-year futures vol spikes > 1.5× typical, tighten stops or scale partial profits.

Skew Inversion: If IV(TM V put) > 35% or Skew Ratio > 0.85 without realized move, close or roll.

Event Day Execution

If TMV falls > 20% by midday, sell 50% of position (locking in intrinsic > $10).

Let remainder run into deeper collapse (e.g., TMV → $29).

Post-Fed, if vol collapses, close to lock gains, as time value vanishes.

Risk Controls

Max Loss: Premium only (e.g., $2k).

Stop-Loss: If put < $0.50 by June 16 without dovish signals, exit at 50% loss.

Discipline: Position ≤ 3% of portfolio to avoid being over-levered on a potentially wrong call.

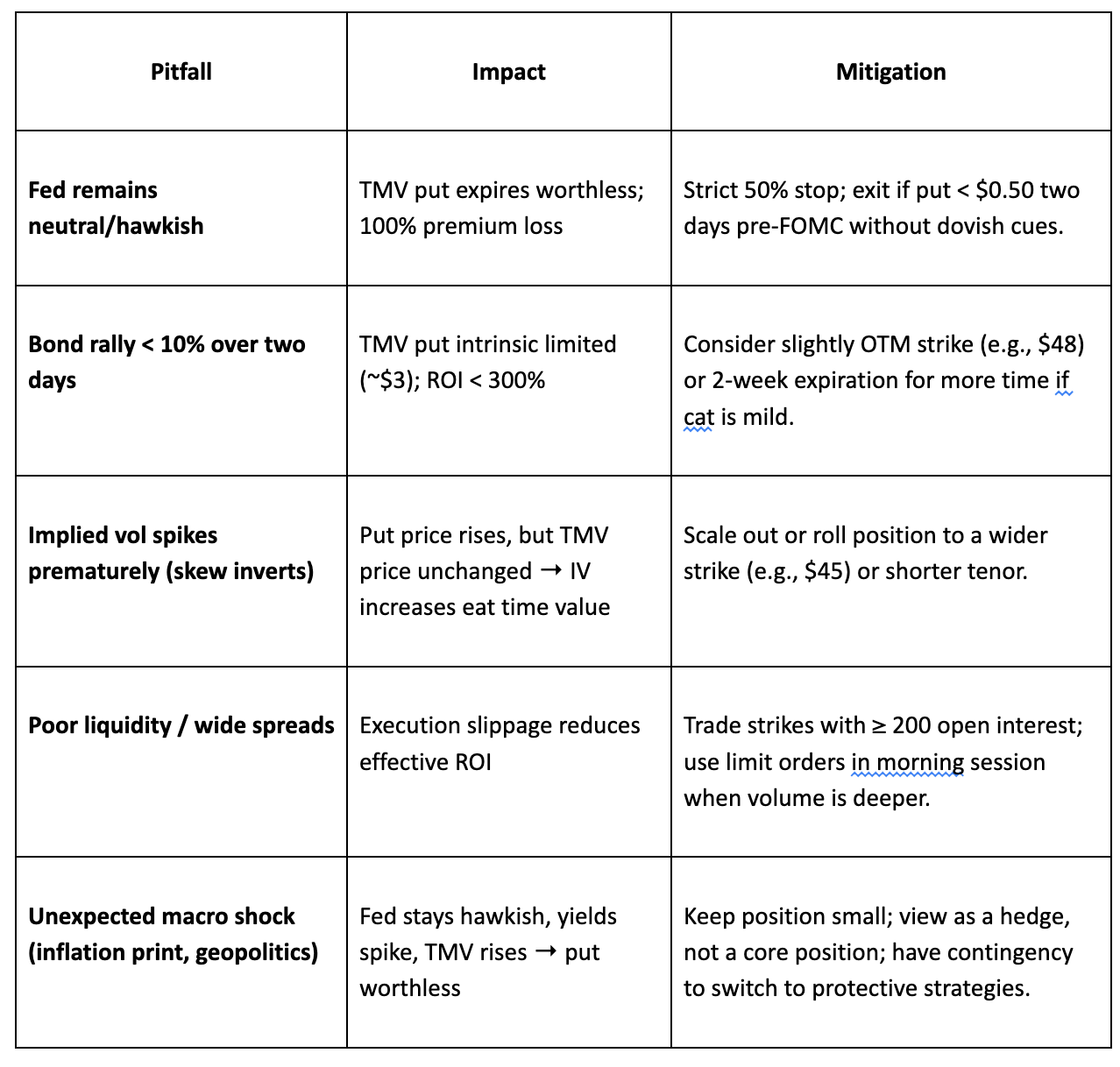

8. Practical Considerations & Pitfalls

Volatility skew in options markets exemplifies how behavioral biases like loss aversion translate into tangible pricing anomalies. Investors’ tendency to overweight losses leads to overpricing of downside protection—embedding a fear premium in put options. In U.S. Treasury options, especially via leveraged ETFs such as TMF and TMV, this skew is evident around major policy events. Traders’ clamoring to hedge yield spikes (bond crashes) ahead of Fed meetings drives up IV on TMF puts and TMV calls, while TMV puts and TMF calls (bets on a dovish outcome) remain underpriced.

A disciplined, well-informed trader can exploit this inefficiency by buying short-dated TMV puts ahead of a dovish Fed surprise. The compelling need for a Fed cut—supported by cooling inflation (CPI/PCE moderation), labor market softening, fiscal sustainability concerns, and consumer credit pressures—makes an unexpected dovish pivot plausible in June 2025. A dovish surprise would send yields sharply lower, causing TMV to collapse and TMV puts to appreciate dramatically. Leveraged ETFs amplify this payoff, turning a $1 premium into $20–$25 of intrinsic value in an extreme move.

By marrying behavioral finance theory with empirical evidence and monetary policy fundamentals, this report demonstrates how academic insights can translate into actionable, tactical strategies. For professional investors, the TMF/TMV case study underscores a broader lesson: when markets are driven by repetitive fear, one can often profit by recognizing when skew has overshot reality and positioning accordingly—always with rigorous risk controls in place.

The Rockefeller Pivot: The Tale of Two Timeless Empires

How the Fall of a Monopoly Forged a New American Power

The story of John D. Rockefeller is often told as a tale of two distinct empires. The first was an industrial leviathan of the 19th century: the Standard Oil Trust, an entity built on ruthless efficiency, coercive economic force, and an unwavering pursuit of monopoly that came to control nearly 90% of the American petroleum market. This empire was tangible, forged in refineries and pipelines, and its power was absolute until it was shattered by the United States Supreme Court in 1911. The second empire, however, was a far more modern and resilient construct of the 20th century. It was an empire of influence, built not on coercion but on the sophisticated "soft power" of scientific philanthropy, professional public relations, and global finance. This transformation—the Rockefeller "pivot"—was not a singular event but a complex and masterful adaptation to a confluence of legal, social, and political pressures that fundamentally reshaped the American landscape.

This report will analyze the multifaceted nature of this pivot, arguing that the fall of the Standard Oil monopoly was the necessary catalyst for the rise of a new, more durable form of Rockefeller power. It will explore how the landmark 1911 antitrust ruling, a violent labor crisis in 1914, and the sweeping national reforms of the Progressive Era collectively forced a strategic metamorphosis. The central question is not simply whether this change was an act of public-spirited atonement or a brilliant maneuver to preserve and expand power, but how it was an inseparable combination of both. In navigating these crises, the Rockefeller dynasty forged a new architecture of influence—one that integrated corporate wealth with public goodwill, and private strategy with national policy—creating a durable blueprint for elite power that remains profoundly influential today.

Part I: The Leviathan Bounded— The Fall of the Standard Oil Trust

The Gospel of Efficiency and Excess

The construction of the Standard Oil monopoly in the late 19th century was a testament to John D. Rockefeller's strategic genius and relentless ambition. The company's growth was fueled by a dual strategy of increasing sales and aggressive acquisitions. After purchasing competing firms, Rockefeller would shut down those he deemed inefficient while absorbing the rest into his ever-expanding enterprise. By early 1872, Standard Oil had acquired nearly every refinery in Cleveland, a major industry hub, and controlled roughly 25% of the American refining market.

The cornerstone of this dominance, however, was not merely superior business practice but the leveraging of market power to secure secret and discriminatory arrangements with the railroads. Through under-the-table deals, threats, and bribery, Rockefeller obtained preferential shipping rates and rebates that gave his companies an insurmountable advantage. One seminal 1868 deal with the Lake Shore Railroad granted Standard a 71% discount on its listed rates in exchange for guaranteed high-volume shipments. These secret transport deals allowed Standard to dramatically undercut competitors, helping its kerosene price drop from 58 to 26 cents between 1865 and 1870, thereby driving rivals out of business. By the turn of the century, the Standard Oil Trust, a complex holding company structure designed to circumvent state laws limiting corporate scale, controlled approximately 90% of the refined oil in the United States.

This concentration of power did not go unnoticed. A rising tide of public resentment, fueled by a new generation of investigative journalists, began to turn against the great trusts. The most influential of these "muckrakers" was Ida Tarbell. Her meticulously researched nineteen-part series, The History of the Standard Oil Company, published in McClure's Magazine from 1902 to 1904, exposed the company's "immoral acts" and "shady dealings" to a national audience. Tarbell, whose own father had been a victim of Rockefeller's business practices, created a "public firestorm" that galvanized anti-monopoly sentiment and created the political will for decisive government action.

The Judgment of 1911

The federal government brought suit against Standard Oil Company of New Jersey, the central holding company of the trust, alleging that its acquisitions and anticompetitive actions constituted a violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890. The case, Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey v. United States, became the most contentious business case of its time to reach the Supreme Court.

On May 15, 1911, the Court, led by Chief Justice Edward D. White, delivered its landmark decision. It found that the Rockefeller conglomerate had illegally monopolized the American petroleum industry and was engaged in an unreasonable restraint of trade. The Court ordered the trust to be dissolved, breaking the massive holding company into 34 separate and theoretically competing companies.

However, the ruling contained a crucial and enduring nuance. Rather than interpreting the Sherman Act as a blanket prohibition on all "combinations in restraint of trade," the Court established what became known as the "rule of reason". Chief Justice White argued that the law forbade only unreasonable monopolies and combinations—specifically, those that led to one of three negative consequences: higher prices, reduced output, or reduced quality. This interpretation, while finding Standard Oil guilty of unreasonable restraint, created a more flexible judicial standard for future antitrust cases. Justice John Marshall Harlan, in a concurring opinion, agreed with the dissolution of Standard Oil but sharply criticized the rule of reason as a judicial invention inconsistent with the clear, unequivocal language of the statute. This new legal framework simultaneously dismantled the nation's most powerful monopoly while providing a pathway for other large corporations to defend their scale, so long as their actions were not deemed "unreasonable."

The Paradox of Defeat

While the Supreme Court's verdict was a legal and political defeat for Standard Oil, its financial consequences were paradoxically beneficial for Rockefeller and his fellow investors. The court's order did not expropriate their assets. Instead, it mandated that the stockholders of the parent holding company receive fractional, pro-rata shares in each of the 34 newly independent companies that were formed. This meant that Rockefeller and his partners now held substantial stakes—in Rockefeller's case, often around 25%—in the companies that would become the future giants of the industry, including Exxon (Standard Oil of New Jersey), Mobil (Standard Oil of New York), and Chevron (Standard Oil of California).

The market responded to this new, competitive landscape with enthusiasm. Investors anticipated that the individual successor companies, now freed from the centralized control of the trust, would innovate and compete more aggressively. As a result, the combined market value of the individual parts soon far exceeded the value of the original monolithic entity. The dissolution, intended to diminish Rockefeller's power, had the counterintuitive effect of making him and other key investors "insanely rich". This legal defeat was not a simple loss but a forced strategic transformation. The state had successfully eliminated the legal form of the monopoly, but in doing so, it had unlocked and vastly multiplied the financial power of its owners. This immense new liquidity created a new challenge for Rockefeller: how to legitimize and deploy this even greater fortune in a Progressive Era political climate deeply hostile to such concentrations of wealth. The court's judgment, therefore, was not the end of the Rockefeller empire, but the financial beginning of its next, more sophisticated chapter.

Part II: The Crucible: Public Condemnation and the Imperative to Change

"The Deadliest Strike in the History of the United States": The Ludlow Massacre

If the 1911 Supreme Court case was a challenge to Rockefeller's business model, the Ludlow Massacre of 1914 was a catastrophic assault on his moral legitimacy. The event was the seminal incident of the Colorado Coalfield War, a protracted and violent strike organized by the United Mine Workers of America against the Rockefeller-controlled Colorado Fuel and Iron Company (CF&I). Miners and their families, who lived in company-owned towns and were paid in company script, were protesting brutal working conditions, low pay, and the company's absolute control over their lives.

When the strike began, CF&I evicted the miners from their company homes, forcing them to establish makeshift tent colonies. On April 20, 1914, at the largest of these colonies near Ludlow, Colorado, an attack was launched by soldiers of the Colorado National Guard and private guards employed by CF&I. Using machine guns, they raked the camp of roughly 1,200 people with gunfire. As evening fell, the camp was set ablaze. The deadliest toll occurred when four women and eleven children, who had taken refuge in a pit dug beneath a tent for safety, were trapped and suffocated as the tent above them burned. In total, approximately 21 people were killed in what historian Howard Zinn called "the culminating act of perhaps the most violent struggle between corporate power and laboring men in American history".

John D. Rockefeller Jr., who had managed the family's stake in CF&I since 1911 and had recently testified before a congressional hearing on the strikes, was immediately and widely blamed for orchestrating the massacre. The event became a nationwide scandal, forever linking the Rockefeller name not just to unfair business practices, but to the brutal deaths of women and children. This public condemnation revealed the stark limits of purely economic power. While the 1911 ruling had been a legal and financial problem to be managed, Ludlow was an existential crisis of legitimacy. In the charged atmosphere of the Progressive Era, public opinion had become a potent force that could destroy a reputation and a legacy in a way that no court ruling could.

Inventing Influence: Ivy Lee and the Birth of Public Relations

Faced with a public relations disaster that threatened to make the family name permanently infamous, Rockefeller Jr. recognized that his vast wealth could not, by itself, solve the problem. He could not simply buy his way out of public condemnation. Moving beyond his initial aloofness and dismissal of the miners' concerns, he sought a new kind of expertise. He hired Ivy Lee, a pioneer in the nascent field of public relations.

Lee's strategy was revolutionary for its time. He advised Rockefeller that the family was losing the battle for public support and that the old corporate tactics of silence and denial were no longer viable. Instead, he advocated for a strategy of proactive engagement designed to humanize the Rockefeller name. Lee orchestrated a personal visit by Rockefeller Jr. to Colorado, where he overcame his natural shyness to meet with miners and their families, inspect their homes and working conditions, attend social events, and, most importantly, listen to their grievances. This was a novel approach for a man of his stature, and it garnered widespread and largely positive media attention.

This response marked a fundamental pivot from relying on the hard power of economic dominance to cultivating the soft power of public opinion. The crisis born from the ashes of Ludlow became the crucible for modern corporate public relations. It was a tacit admission that in the new American century, legitimacy had to be earned, not just assumed, and that the power to shape a public narrative was as critical as the power to control a market. The pivot was no longer just a financial strategy; it had become an existential necessity.

Part III: The New Foundation: Building a Legacy Amidst National Reform

A Charter for Mankind: The Rockefeller Foundation

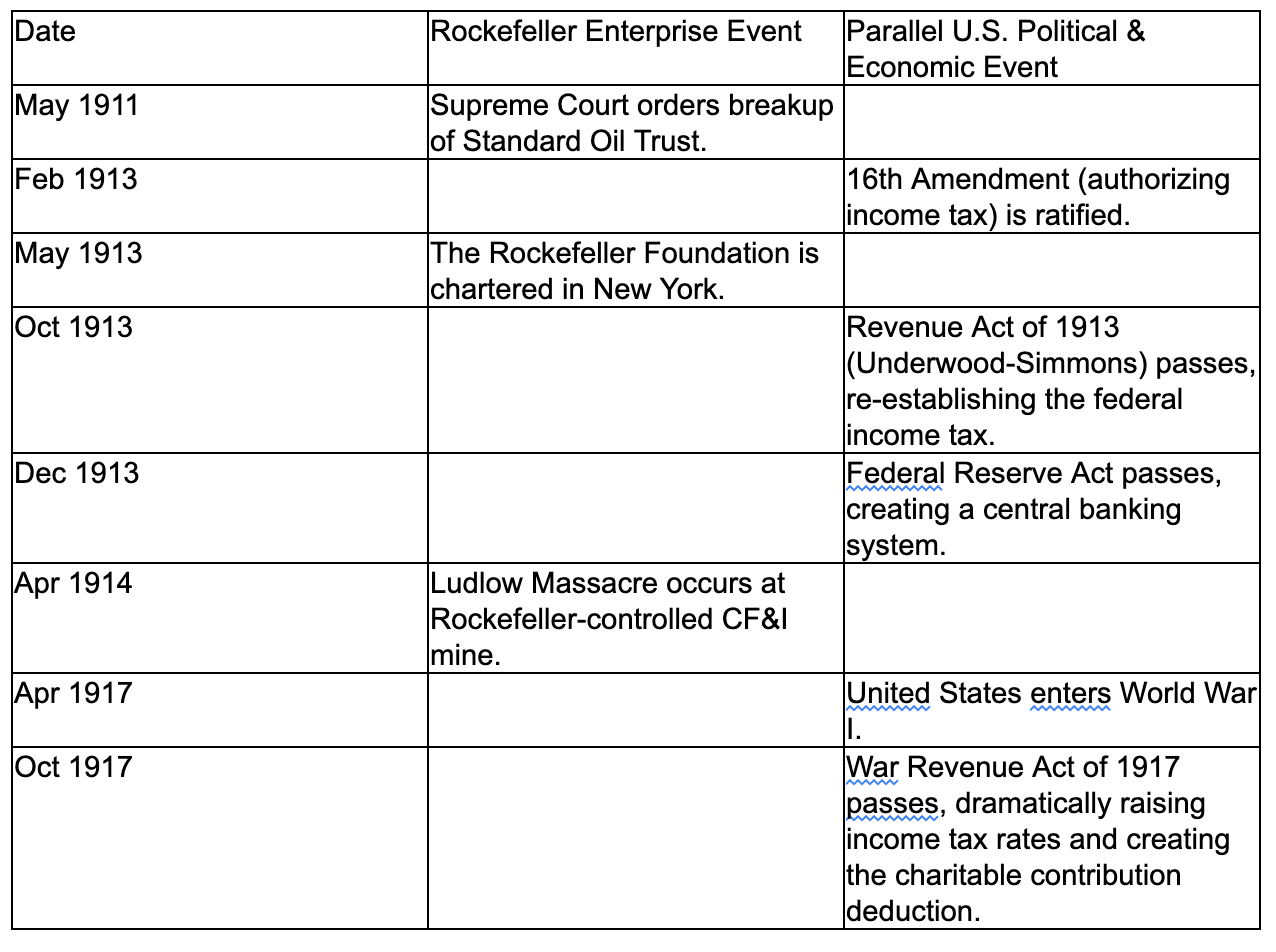

A central pillar in the construction of the new Rockefeller legacy was the establishment of the Rockefeller Foundation. Chartered in New York on May 14, 1913—just two years after the antitrust verdict—the Foundation was endowed with a portion of Rockefeller's immense fortune and given a sweeping, benevolent mission: "to promote the well-being of humanity throughout the world". An earlier attempt to secure a federal charter had been withdrawn due to deep suspicion in Congress related to the ongoing antitrust suit, highlighting the hostile political environment the family faced.

The Foundation's initial activities were large-scale, strategic, and focused on "scientific philanthropy" in areas that were both high-impact and politically non-controversial. It made major grants to establish pioneering institutions like the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health and funded global public health campaigns to eradicate diseases like hookworm and yellow fever. This approach was designed to generate measurable public good and, by extension, to rehabilitate the Rockefeller name. It was a corporate and systematic approach to charity that also served the practical purpose of insulating a significant portion of the family's wealth from potential future inheritance taxes.

The Wilsonian Revolution: Remaking the Rules of Capital

The Rockefeller pivot did not occur in a vacuum. It unfolded against the backdrop of a series of transformative national reforms during the administration of President Woodrow Wilson that fundamentally altered the operating environment for American capital. The old Gilded Age rules were being rewritten, creating both new challenges and new opportunities for a fortune the size of Rockefeller's.

Two pieces of legislation in 1913 were particularly consequential. The Federal Reserve Act, signed on December 23, created a central banking system for the United States. Spurred by the financial panic of 1907, which had exposed the system's instability and its reliance on the intervention of private financiers like J.P. Morgan, the Act shifted control over currency and credit from a handful of powerful Wall Street banks to a new public-private federal entity. A few months earlier, on October 3, the Underwood-Simmons Tariff Act (or Revenue Act of 1913) had dramatically lowered tariffs on imported goods. To compensate for the lost revenue, and enabled by the recently ratified Sixteenth Amendment, the act re-established a federal income tax. This marked a monumental shift in federal revenue policy, moving the primary tax burden away from consumption and placing it directly on the enormous incomes of industrialists like Rockefeller.

This confluence of events in a single year created a new reality. The breakup of Standard Oil had provided Rockefeller with unprecedented liquid wealth, while the new income tax created a powerful incentive to find tax-efficient ways to manage it. The establishment of the Federal Reserve signaled a broader move toward centralized, government-led management of the national economy, diminishing the singular power of private capitalists. The table below illustrates the remarkable proximity of these private and public transformations.

War, Patriotism, and Philanthropy

The entry of the United States into World War I in 1917 accelerated and ultimately institutionalized the Rockefeller pivot. The war required an unprecedented mobilization of the national economy, rendering obsolete the old model where a private firm like J.P. Morgan & Co. could act as the primary financier and purchasing agent for Allied governments. The U.S. government took a direct role, creating powerful new agencies like the War Industries Board, led by financier Bernard Baruch, to coordinate industrial production, and the U.S. Fuel Administration, which relied on the expertise of oil executives like Walter Teagle, the new president of Standard Oil of New Jersey.

War financing was also transformed. Instead of relying on a few large banks, the government partnered with the new Federal Reserve system to launch a mass-participation campaign through the sale of Liberty Loans. These bond drives raised billions of dollars from ordinary citizens, framing financial support for the war as a patriotic duty.

This new model of public-private partnership found its ultimate expression in tax policy. To fund the immense cost of the war, the War Revenue Act of 1917 dramatically increased income tax rates, with the top rate soaring to 67%. Lawmakers, particularly Senator Henry F. Hollis, worried that these heavy new taxes would "dry up" the surplus income from which the wealthy made their donations to colleges, hospitals, and other charities. Fearing the government would then have to assume the financial burden for these institutions, Congress introduced a landmark provision: the charitable contribution tax deduction. This policy effectively created a government subsidy for private philanthropy. It institutionalized the very model Rockefeller had begun pioneering four years earlier. His private solution to a corporate crisis—deploying vast wealth for public good—was now enshrined in the U.S. tax code as national policy, aligning his family's strategic interests with a state-sanctioned vision of civic responsibility.

Part IV: The Empire Reborn: Global Reach in the Post-War World

From Monopoly to Cartel: The Red Line Agreement

The post-war era saw the successor companies of the Standard Oil trust, particularly Standard Oil of New Jersey under the aggressive leadership of Walter C. Teagle, expand their operations globally, acquiring assets in Venezuela, Iran, and across the world. This international expansion culminated in a new, more sophisticated form of market control that demonstrated the full evolution of the Rockefeller strategy.

On July 31, 1928, representatives from the world's most powerful oil companies—including the American firms Standard Oil of New Jersey and Socony (Standard Oil of New York), Britain's Anglo-Persian Oil Company, Royal Dutch Shell, and the Compagnie Française des Pétroles—signed the Red Line Agreement. This pact was designed to jointly control the exploration and development of the vast, untapped oil resources within the territory of the former Ottoman Empire. The agreement's most critical feature was a "self-denying clause," which prohibited any of the partners from independently seeking oil concessions within the area demarcated by a red line drawn on a map of the Middle East.

This agreement effectively created a massive international oil cartel. It achieved the same essential goals as the old Standard Oil Trust—stabilizing prices, controlling supply, and limiting competition—but did so on a global stage. The illegal and publicly reviled domestic monopoly of the 19th century was replaced by a legal, state-sanctioned international consortium in the 20th. This new structure operated far from the reach of the Sherman Antitrust Act and with the tacit approval of the respective home governments, which saw it as a tool of geopolitical influence. The pivot was complete: the goal was never to abandon market control, but to find a new, more stable, and legally defensible way to exercise it.

The Banker's Hand: Rockefeller Influence in Finance

Simultaneously, the center of gravity of the Rockefeller family's power continued its shift away from direct industrial management and toward the more abstract and flexible domain of finance. The family's immense wealth was locked up in a series of trusts, established in 1934 and 1952, which were administered by Chase Bank. This began a long and powerful association with what would become Chase Manhattan Bank, an institution often referred to as "David's bank" during the tenure of David Rockefeller.

Furthermore, the family forged a powerful dynastic and business alliance with National City Bank (the future Citibank). The bank's president, James Stillman, was a close associate of William Rockefeller (John D.'s brother), and Stillman's two daughters married William's two sons, Percy and William Goodsell Rockefeller. James Stillman Rockefeller, a grandson, would later serve as president and chairman of National City Bank. This deep entrenchment within the nerve centers of American finance provided a less visible but arguably more durable and pervasive form of power than owning oil fields and refineries. It represented the final stage of the transformation from industrial baron to financial patriarch, demonstrating a clear strategic choice to control not just a product, but the system of capital itself.

The Durable Architecture of Modern Power

The Rockefeller pivot was a masterful and necessary response to a convergence of crises that threatened to destroy the family's empire and legacy. The 1911 Supreme Court ruling made its 19th-century business model illegal, the 1914 Ludlow Massacre made its public image morally indefensible, and the political reforms of the Progressive Era fundamentally altered the rules of American capitalism. In response, the Rockefellers did not retreat; they reinvented their relationship with the public and the state.

The transformation from a brittle monopoly built on coercion to a resilient ecosystem of influence was not an abandonment of power, but its modernization. The illegal domestic trust was replaced by a sanctioned international cartel. Direct economic control was supplemented by the soft power of "scientific philanthropy," a practice that was ultimately subsidized and encouraged by the very government that had once sought to break the family's power. The crude tactics of railroad rebates and price wars gave way to the sophisticated art of public relations, shaping narratives and manufacturing consent.

This new architecture of power—seamlessly integrating immense corporate wealth, strategic tax-advantaged philanthropy, professional public relations, and deep control over the commanding heights of finance—did more than just rescue the Rockefeller name from the brink of infamy. It created a durable and sophisticated blueprint for corporate and elite influence that would define the American century. It demonstrated that true power in the modern era lay not merely in controlling an industry, but in shaping the legal, social, and political environment in which all industries operate.

The Through-Line: How the Nation State, Speculators, and Paper Make (and Break) History

The Machine

The year is 1872. A German industrialist, buoyed by the euphoria of national unification and the flood of French indemnity payments, enters the newly constructed Berlin Börse. Beneath its soaring galleries, amidst a cacophony of voices and the frantic ticking of the telegraph, he approaches a licensed broker, a Makler, to execute a Börsentermingeschäft—a time bargain—on one hundred shares of the burgeoning Krupp steel works. The terms are simple: a price is agreed upon, and delivery and payment are deferred to the end of the month. A clerk records the transaction on a slip of paper and posts the Einschuss, or margin, with a clearing agent. No shares change hands. The industrialist is not buying steel capacity; he is buying time and leverage, speculating on a future price. When the contract matures, he will likely settle not by taking delivery of the shares, but by receiving or paying the cash difference, a pure play on market sentiment. The entire operation is underwritten by the implicit guarantee of the new German Empire and its powerful Goldmark.

The year is 2006. A hedge fund manager in Greenwich, Connecticut, stares at a bank of glowing monitors. With a few keystrokes, she instructs her prime broker to purchase a specific mezzanine tranche of a Collateralized Debt Obligation (CDO) squared, a security synthetically constructed from the risk of thousands of subprime mortgages originated in distant states she will never visit. The transaction is governed by a standardized ISDA Master Agreement. The perceived risk of the position is offset by purchasing a credit default swap, a financial instrument that functions as a modern Prämie or premium. The leverage for the trade is not provided by deferred settlement, but by an overnight repurchase agreement (repo), where the CDO tranche itself serves as collateral. The entire global architecture of this trade is backstopped by the invisible but ever-present assumption of a Federal Reserve put—the belief that the central bank will intervene to prevent systemic collapse.

Though separated by 134 years, a technological chasm, and a world of different terminologies, the financial choreography is identical. An asset of the age—industrial shares, mortgage-backed securities—is transformed into a speculative instrument. Its value is leveraged not with existing capital, but with a promise of future payment. A secondary market in these promises allows for speculation on speculation. And the entire edifice rests on a backstop, implicit or explicit, provided by a sovereign or central banking authority.

This report argues that these are not isolated episodes of speculative mania. They represent a single, continuous arc of financial engineering, a recurring machine that has driven the great boom-bust-war cycles of the modern era. The thesis is that every one of these cycles rides the same fundamental engine: a state goal that requires more money than taxes can raise leads to financial engineering that multiplies purchasing power off-balance-sheet; this, in turn, fuels speculative leverage in "term" or option-like paper, which inevitably culminates in crisis and social fracture, followed by a political re-armoring. From Tulipmania to today, only the paperwork and the branding change; the incentive plumbing remains the same.

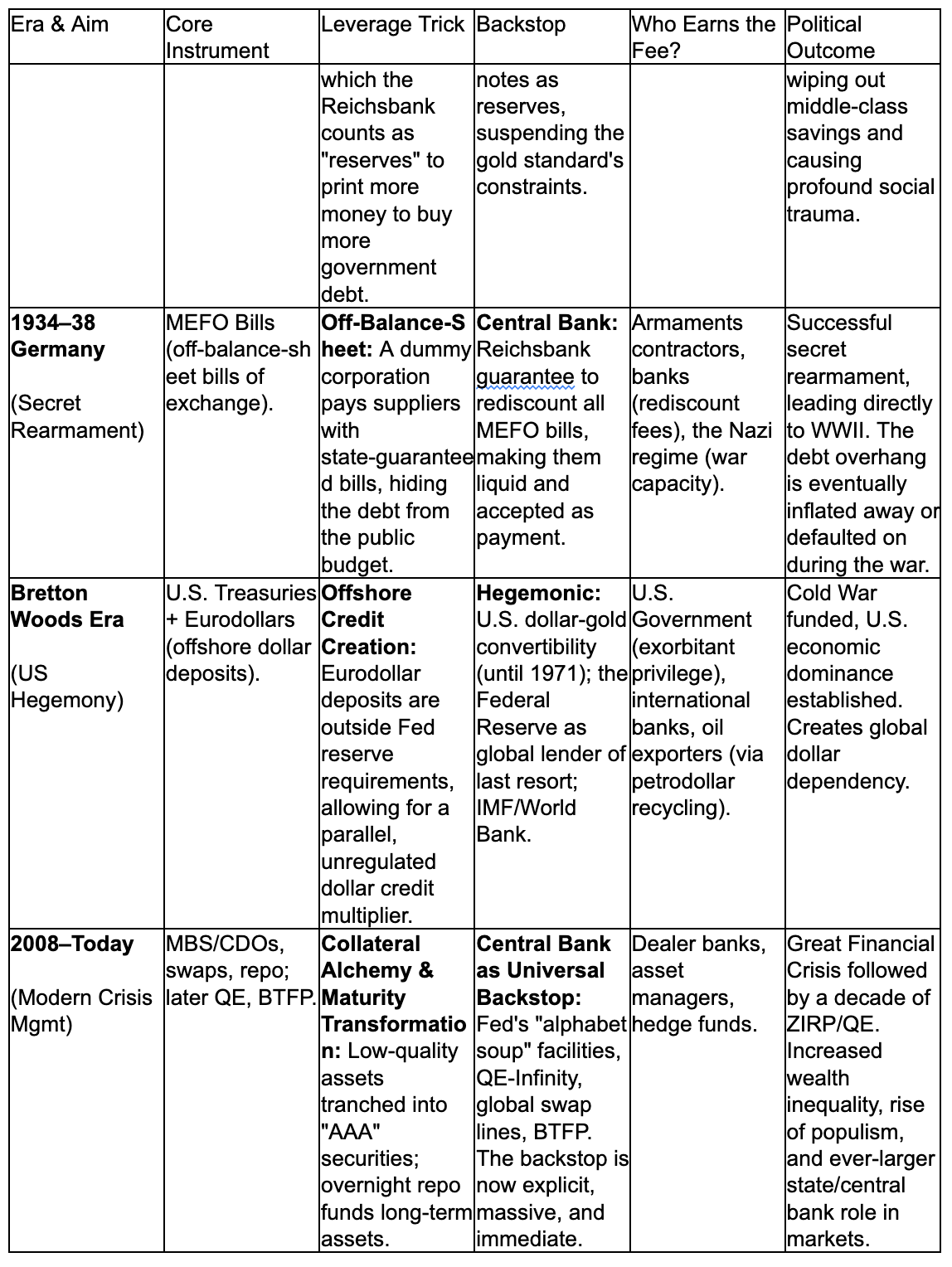

The Genesis of the Machine: Tulips, Debt, and the Dawn of Modern Paper (1630s–1720s)

The foundational mechanics of modern financial cycles were forged in the 17th and early 18th centuries. Two distinct but related episodes—the Dutch Tulipmania and the state-sponsored debt bubbles in Britain and France—established the core template: the creation of tradable paper representing a future claim, the use of deferred settlement to generate leverage, and the critical role of a social or sovereign backstop in both encouraging the boom and managing its collapse. These early experiments were prototypes, revealing the immense power of financial engineering to mobilize capital and the profound social and political risks it entailed.

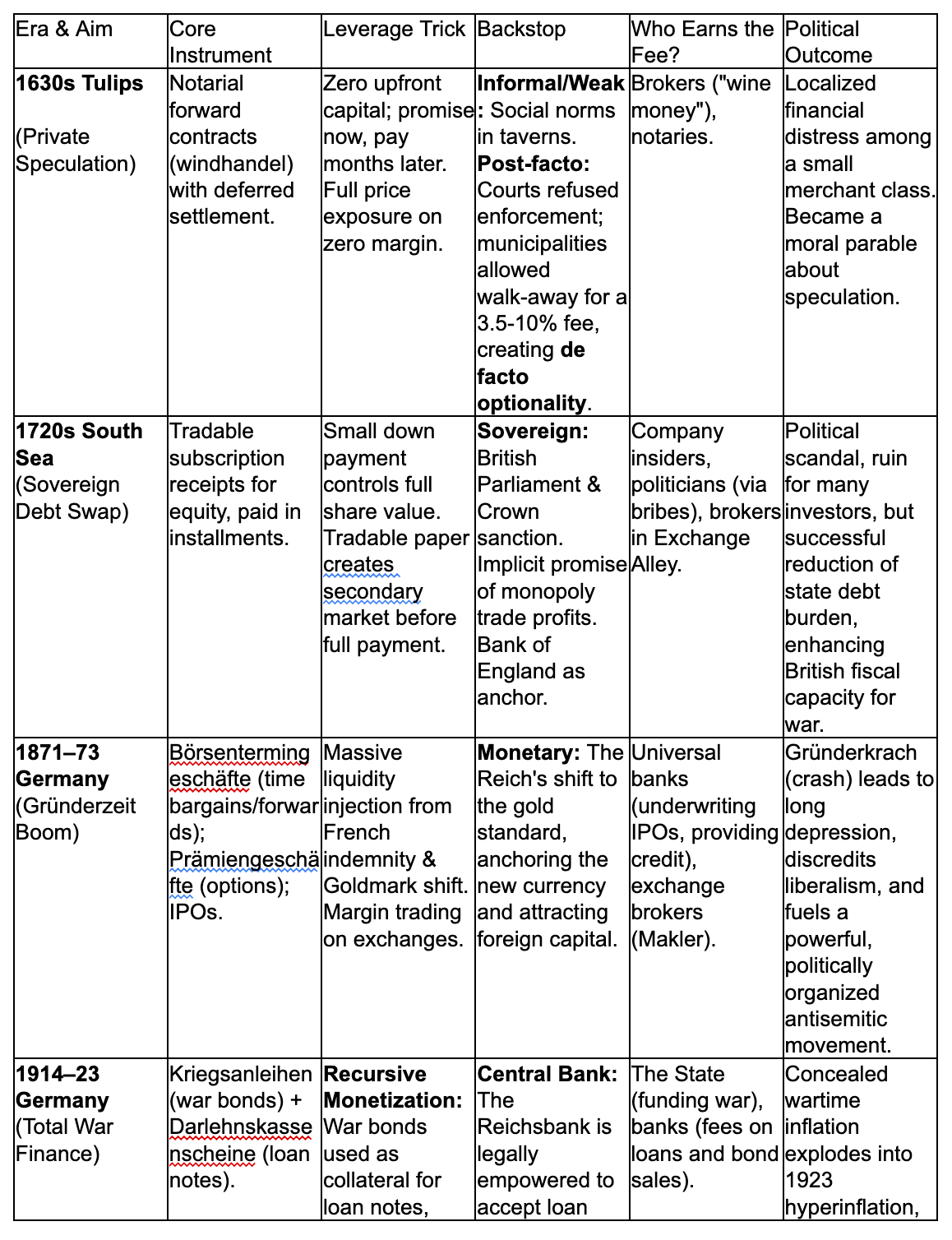

A. Tulipmania (1630s): Leverage Without Banks and the Birth of Optionality

While often portrayed as a simple story of irrationality, the Dutch Tulipmania of the 1630s was, more accurately, a sophisticated demonstration of how financial innovation can create a speculative market out of thin air, generating immense leverage without the involvement of formal banking institutions. The episode is most instructive not for the madness of crowds, but for the mechanics of the contracts that enabled it and the legal response that ultimately defined it.

The primary instrument of the bubble's most intense phase was not the physical tulip bulb, but the windhandel (literally, "wind trade")—a forward contract for the future delivery of bulbs. These contracts, typically recorded by notaries, allowed traders to speculate on the price of rare bulbs that were still in the ground and would not be lifted until the end of the growing season, months later. This system of deferred settlement was the engine of leverage. Traders met in informal "colleges" in taverns, where buyers were required to pay only a small "wine money" fee, often less than 3% of the trade value. Crucially, neither party posted an initial margin, meaning a speculator could gain exposure to the full price movement of a valuable asset with virtually no capital down. This structure, promising cash later for a claim today, functioned as a highly leveraged futures market, driven by a classic herd mentality and the fear of missing out on seemingly endless price appreciation.

The initial backstop for this market was purely social: trust and honor within a close-knit community of merchants and florists. However, when the market collapsed abruptly in February 1637, this informal system proved entirely inadequate. Buyers defaulted en masse, and the contracts became worthless. The response of the Dutch legal system was the episode's most significant financial innovation. Courts largely refused to enforce the windhandel contracts, viewing them as gambling debts rather than legitimate commercial agreements. In the aftermath, municipalities and guilds arbitrated settlements that allowed buyers to be released from their obligations by paying a small penalty, a fixed percentage of the contract price, typically between 3.5% and 10%.

This post-facto legal re-armoring had a profound effect: it retroactively converted what had been structured as a binding forward contract into a call option. The agreed-upon contract price effectively became the strike price, and the walk-away penalty became the option premium. This reveals a fundamental principle of financial architecture: the true nature of a financial instrument is defined not merely by its written terms, but by the legal and political backstop that governs its enforcement in a crisis. The Tulipmania established a precedent where private gains were kept, but catastrophic losses were mitigated by transforming the nature of the underlying obligation.

B. The Sovereign's Gambit: The South Sea and Mississippi Schemes (1719–1721)

Nearly a century later, the principles of paper-based leverage were adopted and scaled up by the most powerful economic actors of the age: the states of Britain and France. The South Sea and Mississippi bubbles were not spontaneous market manias but deliberate acts of state policy, designed to solve a crippling problem of public finance through financial engineering.

The state's purpose was explicit: to manage the enormous national debts incurred during the War of the Spanish Succession. The core mechanism was a grand debt-for-equity swap. The British government chartered the South Sea Company, and the French regent empowered Scottish financier John Law's Mississippi Company, to assume large portions of the national debt. Holders of illiquid, long-term government annuities were offered the chance to exchange them for shares in these new, dynamic trading companies, which were granted lucrative monopolies on trade with the Americas. The "bubble" was not an accident; it was the essential ingredient required to make the scheme work. To entice debt-holders, the company shares had to appear far more valuable than the government paper they were replacing.

The key financial instrument used to generate this perception of value was the subscription list, a formalized version of the deferred settlement seen in Tulipmania. To buy shares in a new offering, investors were required to pay only a fraction of the price upfront—often just 10% or 20%—with the remainder due in a series of future installments. These subscription receipts were themselves tradable, creating a highly leveraged secondary market where speculators could profit from rising share prices before the stock was even fully paid for. This installment system dramatically broadened market participation and fueled a self-reinforcing spiral of demand.

Unlike the informal social norms of the tulip market, the backstop for these schemes was the full faith and credit of the sovereign. The British Parliament passed the South Sea Act, lending the company immense prestige and an implicit government guarantee. John Law's system in France was even more audacious: his Banque Générale was nationalized as the Banque Royale and given the authority to issue paper currency. This new money could then be used to buy shares in the Mississippi Company, creating a recursive feedback loop where the central bank printed money to inflate the asset that was supposed to absorb the state's debt.

When these bubbles inevitably collapsed in 1720, the result was widespread financial ruin and political scandal, with government ministers and company directors accused of corruption and insider trading. Yet, from the state's perspective, the policy was a partial success. The South Sea scheme, in particular, did succeed in converting a significant portion of high-interest, intractable government debt into lower-interest, more manageable corporate obligations, arguably strengthening Britain's fiscal position for future conflicts. The pattern was thus established: a state objective is funded through engineered paper that delays cash payment, creating a speculative secondary market. When the bubble bursts, private losses are immense, but the state's strategic goal is often achieved, and the system is politically re-armored for the next cycle.

The German Crucible: A Century of Financial Warfare (1871–1948)

If the 17th and 18th centuries provided the prototype, it was Germany between its unification in 1871 and its collapse in 1945 that refined the machine of state-driven finance into its most potent and destructive forms. Over seventy-five years, Germany provided a high-definition case study of the entire cycle, repeated multiple times with increasing intensity. It demonstrated how a sudden liquidity shock could fuel a speculative boom, how the resulting crash could be weaponized politically, and how financial innovation could be systematically harnessed first to regulate the market, then to fund total war, and finally to enable a totalitarian regime's ambitions. The German experience reveals, with chilling clarity, how financial instruments are never neutral tools, but are deeply embedded in the geopolitical and ideological projects of the state.

A. Unification to Gründerkrach (1871–1879): The Indemnity Boom

The birth of the German Empire was accompanied by a massive financial shock. The victory over France in 1871 yielded a war indemnity of 5 billion gold francs, an immense sum that was injected directly into the new nation's economy. This capital influx was supercharged by a simultaneous monetary reform: Germany abandoned its silver-based currencies and adopted the Goldmark, aligning itself with the international gold standard dominated by Great Britain. This dual shock—a fiscal windfall and a monetary realignment—unleashed a torrent of credit and fueled a speculative boom known as the Gründerzeit, or "Founders' Era".

The Berlin Börse became the epicenter of this boom. Hundreds of new joint-stock companies were founded and taken public in a wave of IPOs, particularly in railways and heavy industry. Speculation was facilitated by sophisticated financial instruments that allowed for immense leverage. The two primary vehicles were:

Börsentermingeschäfte (Time Bargains): These were standardized forward contracts for the purchase or sale of shares at a future date, typically the end of the month (ultimo). As in the tulip markets, their power lay in deferred settlement. A speculator could control a large block of shares with only a small margin deposit (Einschuss), and most contracts were settled in cash based on the price difference, making them pure instruments of financial speculation rather than tools for investment.

Prämiengeschäfte (Premium Trades): These were functionally identical to modern stock options. A buyer would pay a small, non-refundable premium (Prämie) for the right, but not the obligation, to buy or sell a stock at a set price on a future date. This offered a defined-risk way to bet on large price swings.

This boom was not contained within Germany; it was a transatlantic affair, with German capital flowing heavily into the bonds of American railroads. The interconnectedness of global finance meant that the collapse was also global. The panic began on the Vienna Stock Exchange in May 1873, when the speculative bubble in Austrian real estate and industrial stocks burst. The crisis immediately spread to Berlin, causing a catastrophic crash—the Gründerkrach—that wiped out countless new companies and investors' savings, ushering in a prolonged economic stagnation that became known as the Long Depression.

The political consequences of the Gründerkrach were arguably more significant and lasting than the economic ones. The crash thoroughly discredited the classical liberal ideology that had dominated the unification era. In the ensuing search for scapegoats, a powerful and politically organized antisemitic movement emerged. Public figures and a burgeoning antisemitic press blamed "Jewish financiers" and "mobile capital" for the speculative excesses and the subsequent economic misery. The crisis provided a potent narrative that fused anti-capitalist sentiment with racial prejudice, portraying a dichotomy between "productive" German industrial capital and "parasitic" Jewish financial capital. This "financialization of grievance" transformed latent anti-Jewish prejudice into a modern political weapon, establishing an ideological foundation that would have devastating consequences in the decades to follow.

B. Regulating Risk: The Exchange Act of 1896

The social and political fallout from the Gründerkrach led directly to the next phase of the cycle: political re-armoring. The widespread public anger over speculative losses created a powerful demand for state intervention to regulate the markets. The most effective political voice for this sentiment was the Bund der Landwirte (Agrarian League), a formidable lobby representing the interests of Germany's powerful landowning class, especially the Prussian Junkers. Facing declining global commodity prices, the Agrarian League blamed their economic woes on the commodity futures exchanges, which they saw as tools of "Jewish" speculators that destabilized prices. Their platform was a direct assault on the liberal, free-market ethos of the Gründerzeit.

Their lobbying efforts culminated in the passage of the German Exchange Act (Börsengesetz) of 1896, a landmark piece of financial regulation. The law was a direct political response to the perceived excesses of the previous boom and was heavily influenced by the agrarian agenda. Its most significant provisions were:

A Ban on Futures Trading: The Act outright prohibited futures trading in grain and milling products, effectively shutting down the Berlin commodity exchange for these goods. It also banned time bargains (Termingeschäfte) in the shares of mining and industrial companies, the very instruments at the heart of the 1870s boom.

Stricter IPO Regulations: The law imposed new, more stringent rules for companies seeking to list on the stock exchange. These included a mandatory one-year waiting period after incorporation before shares could be traded and the requirement to publish a detailed prospectus and financial statements.

The impact of the 1896 Act was twofold. The ban on agricultural futures was widely seen by economists as a mistake that damaged the efficiency of German commodity markets and harmed price discovery for farmers. However, the new rules governing IPOs had a more positive effect. By increasing disclosure requirements and the liability of company promoters, the law appears to have improved the quality of firms going public and increased their long-term survival rates, thereby offering greater protection to investors. This episode exemplifies the re-armoring phase, where the state, driven by a powerful political constituency, steps in to constrain the very financial instruments that defined the preceding crisis.

C. Arms Race to Total War Finance (1900–1923): The Darlehnskassen Engine

As the German Empire entered the 20th century, its primary state goal shifted to military expansion, specifically the naval arms race against Great Britain. Initially, this was funded through conventional means. However, with the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914, Germany unleashed a pre-planned system of "financial mobilization" designed to fund a total war without immediate recourse to politically difficult tax hikes. This system represented a quantum leap in the state's use of financial engineering to create purchasing power.

The cornerstone of this system was the establishment of Darlehnskassen (Loan Bureaus) alongside the suspension of the gold standard. The mechanism was a masterpiece of recursive, off-balance-sheet monetization:

War Bonds (Kriegsanleihen): The government issued massive tranches of war bonds, sold directly to the public through relentless patriotic propaganda campaigns. Citizens were encouraged to turn their savings into an investment in national victory.

Collateralization: A citizen, business, or municipality holding these war bonds (or other securities) could then take them to a newly created Darlehnskasse and use them as collateral for a loan.

Issuance of Loan Notes (Darlehnskassenscheine): The loan was disbursed not in regular currency, but in special loan notes, the Darlehnskassenscheine. These notes were declared legal tender, accepted for all payments to the state.

The Monetary Alchemy: The crucial step was a change in the banking law of August 4, 1914. This law permitted the Reichsbank, Germany's central bank, to include these Darlehnskassenscheine in its legal monetary reserve, treating them as equivalent to gold.

Monetizing the Debt: With its "gold-like" reserves artificially inflated by these notes, the Reichsbank could then legally print more of its own banknotes. It used this newly created money to purchase short-term Treasury bills directly from the government, providing the state with the cash it needed to pay soldiers and arms manufacturers.

This closed loop effectively allowed the government to turn its own debt into the reserve base for the creation of new money. It was a sophisticated method for concealing the true inflationary cost of the war. During the conflict, this inflation was largely suppressed by a command economy of rationing, wage controls, and price ceilings. However, the monetary overhang was immense. After Germany's defeat in 1918, the fragile Weimar Republic was burdened with this hidden inflation, colossal war debts, and the additional weight of punitive reparations payments demanded by the Treaty of Versailles. When France and Belgium occupied the industrial Ruhr region in 1923 to enforce reparations, the German government responded by printing money to pay striking workers. This final push sent the monetary system into freefall, detonating the latent inflation into the hyperinflation of 1923, which vaporized the savings of the German middle class and inflicted a deep and lasting trauma on the national psyche.

D. The 1931 Break and its Political Consequences

The trauma of hyperinflation was followed by a brief period of stabilization, but the global shock of the Great Depression, beginning in 1929, plunged Germany back into crisis. This economic downturn was critically amplified by a severe banking crisis in the summer of 1931. The trigger was the failure of Austria's largest bank, the Creditanstalt, in May, which sent shockwaves through the interconnected German banking system.

Confidence was further shattered by the aggressive foreign policy of Chancellor Heinrich Brüning. His government's surprise announcement of a customs union with Austria and his public demands for an end to all reparations payments torpedoed international trust in Germany's financial stability. This led to a massive flight of foreign capital, as international creditors pulled their short-term loans from German banks. The panic culminated in a run on deposits that forced the failure of one of Germany's largest and most prestigious universal banks, the Darmstädter und Nationalbank, or Danatbank, in July 1931. The government was forced to declare a bank holiday and impose capital controls, but the damage was done.

The 1931 banking crisis acted as a powerful political accelerant for the Nazi Party. Recent economic history, using newly compiled microdata on bank-firm relationships, has established a direct causal link between the financial shock and the rise of Nazism. The analysis shows that the surge in votes for the Nazi Party between the 1930 and 1932 elections was significantly greater in cities and towns whose local economies were more heavily dependent on firms financed by the failed Danatbank. The economic distress caused by the credit crunch translated directly into votes for a radical party.

Furthermore, the effect was amplified by pre-existing cultural factors. The Nazi electoral gain was strongest in localities with a documented history of antisemitism. The Nazi propaganda machine expertly exploited the fact that the chairman of the Danatbank was a prominent Jewish financier, Jakob Goldschmidt. The bank's failure was presented as tangible, irrefutable proof of the central Nazi claim that an international Jewish financial conspiracy was deliberately destroying Germany. The crisis provided the ultimate focal point for the "financialization of grievance," turning abstract antisemitic ideology into a simple, compelling explanation for the very real economic pain felt by millions of Germans.

E. Rearmament Paper and War (1934–1945): The MEFO Bill

Upon taking power in 1933, the Nazi regime's primary objective was rapid and massive rearmament, a direct violation of the Treaty of Versailles. This presented a formidable financial challenge: how to fund this enormous industrial undertaking secretly, without access to international capital markets, and without triggering the hyperinflation that had scarred the nation only a decade earlier. The solution, devised by the brilliant and cynical Reichsbank President Hjalmar Schacht, was the MEFO bill—the most sophisticated instrument of off-balance-sheet state finance yet conceived.

The MEFO bill system was a refinement of the Darlehnskassen model, engineered for maximum deception:

The Dummy Corporation: A shell company with a deliberately innocuous name, Metallurgische Forschungsgesellschaft, m.b.H. (Metallurgical Research Corporation), or MEFO, was established. It was nominally owned by a consortium of major German industrial firms like Krupp and Siemens but was, in reality, an instrument of the state.

Off-Budget Payment: When an armaments firm delivered tanks or aircraft to the military, the Treasury did not pay them with Reichsmarks from the official state budget. Instead, it authorized MEFO to "pay" the contractor by issuing a bill of exchange—a MEFO bill—for the value of the goods.

State-Guaranteed Liquidity: The MEFO bill was a promise to pay in six months, but crucially, it came with a guarantee from the Reich that its maturity could be extended for up to five years. More importantly, the Reichsbank guaranteed that it would rediscount any MEFO bill presented to it by any German bank. This guarantee made the bills highly liquid and readily accepted throughout the economy. An arms contractor could take its MEFO bill to its local bank and immediately receive cash (minus a discount), confident that the bank could, in turn, cash it in at the Reichsbank.

The MEFO system allowed the Nazi regime to finance its rearmament through a parallel, clandestine monetary circuit. By 1938, it had been used to fund 12 billion Reichsmarks of military spending—an amount equivalent to more than half of the entire official national debt—completely off the public books. It was a tool of sovereign deception, enabling a state to break international law and prepare for war while maintaining a facade of fiscal prudence.

This principle of synthetic, off-balance-sheet funding was extended to occupied Europe during the war through the mechanism of bilateral clearing accounts. When a French firm, for example, exported goods to Germany, it was paid in francs by the Bank of France. However, the Bank of France was not reimbursed by Germany with foreign currency. Instead, it was credited with a balance in a "clearing account" at the Reichsbank. These were phantom credits that could never be spent. This system forced occupied nations to extend unlimited, involuntary credit to the Reich, effectively making them pay for their own occupation and financing the German war effort. The MEFO bill and the clearing account were the ultimate expressions of the financial machine, turning paper promises into the instruments of total war.

WWII to Cold War: The Dollar Turns the Trick at Scale

The end of the Second World War marked a fundamental shift in the global financial architecture. The German model of opaque, off-balance-sheet war finance was superseded by a new system, designed and dominated by the United States. While seemingly more transparent and rule-based, the post-war order, centered on the U.S. dollar, replicated the core functions of the old machine on a global scale. U.S. war finance, the Bretton Woods system, and the subsequent rise of the Eurodollar market created a new form of hegemonic financial plumbing that enabled the United States to fund its Cold War ambitions and project power in a manner its predecessors could only envy.

U.S. financing for World War II differed significantly in its execution from the German approach. Instead of resorting to complex off-balance-sheet vehicles like MEFO bills, the American war effort was funded through a more direct and transparent, though equally massive, mobilization of the nation's financial resources. The primary instruments were publicly issued Treasury bonds ("War Bonds"), supported by a patriotic public campaign, high levels of taxation, and a system of administered interest rates where the Federal Reserve pegged the yield on government debt. This was complemented by rationing and price controls, which suppressed inflation and crowded out private credit, channeling all available economic capacity toward war production. The success of this model, combined with vast gold inflows from a war-torn Europe, cemented the U.S. dollar's position as the world's preeminent currency.

This dominance was formalized in the Bretton Woods Agreement of 1944. The new architecture established a global system of fixed exchange rates, with all member currencies pegged to the U.S. dollar. The dollar, in turn, was the only currency directly convertible to gold at a fixed rate of $35 per ounce. This arrangement granted the United States what Valéry Giscard d'Estaing would later call an "exorbitant privilege." As the issuer of the world's reserve currency, the U.S. could finance its external deficits simply by printing more dollars, which other nations were obliged to accept and hold as reserves. The newly created International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank were designed to manage this system, providing liquidity to smooth over temporary balance-of-payments shocks and financing post-war reconstruction, respectively.

However, just as in previous eras, a parallel, off-balance-sheet system soon emerged that amplified the power of the core architecture. This was the Eurodollar market. Eurodollars are simply U.S. dollar-denominated deposits held in banks outside the United States. The market emerged in the 1950s as foreign entities, including the Soviet Union, sought to hold their dollar earnings outside the direct jurisdiction of U.S. authorities. The crucial feature of this market was that these offshore dollar deposits were not subject to the U.S. Federal Reserve's domestic banking regulations, most importantly, reserve requirements.

This regulatory arbitrage turned the Eurodollar market into a powerful engine of offshore credit creation—a parallel Darlehnskassen system for the entire globe. A dollar deposited in London or Zurich could be lent out with a much smaller reserve cushion than a dollar deposited in New York, creating a "dollar multiplier" outside the control of the Fed. This vast, stateless pool of dollar liquidity fueled global trade and investment but also provided a new, flexible source of financing for U.S. corporations and the U.S. government itself.

The system was further reinforced by the rise of "petrodollar recycling" after the oil shocks of the 1970s. Oil-exporting nations, primarily in the Middle East, amassed enormous U.S. dollar surpluses. Unable to invest all of this capital in their own small economies, they recycled it back into the global financial system, primarily by purchasing U.S. Treasury securities and making large deposits in international banks. This created a stable, self-reinforcing loop: the world's demand for oil ensured a constant demand for U.S. dollars, and the resulting petrodollar surpluses were then used to finance U.S. government deficits. This continuous financing of U.S. spending, particularly on defense, functioned as a transparent, market-based version of the MEFO bill system. Instead of a secret dummy corporation, the visible U.S. Treasury market became the vehicle for funding state ambitions, with foreign central banks and sovereign wealth funds willingly playing the role of the rediscounting banks.

When President Nixon severed the dollar's final link to gold in 1971, ending the formal Bretton Woods system, this underlying plumbing remained and, if anything, became more important. In the new era of floating fiat currencies, the U.S. retained its exorbitant privilege. The U.S. Treasury market became the world's primary reserve asset, the ultimate safe haven, and the Federal Reserve evolved into the meta-rediscount house for the entire global financial system, providing dollar liquidity through open market operations and, eventually, quantitative easing and international swap lines. The machine was now global in scale, with the dollar as its universal operating system.

The Modern Wrapper (1980s–Today)

The final decades of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st witnessed an explosion in financial innovation that gave the age-old machine a dazzling new set of wrappers. The fundamental jobs of the financial system—term extension, leverage creation, and maturity and collateral transformation—remained the same, but they were now executed with unprecedented speed, complexity, and scale. Instruments like swaps, futures, and options were standardized and traded on a massive scale. Securitization allowed illiquid assets like mortgages and auto loans to be packaged into tradable securities. The repo market and prime brokerage services provided nearly unlimited leverage to institutional players. While the technology changed, the choreography of crisis remained remarkably consistent, culminating in a series of shocks that each required an ever-larger intervention from the state's ultimate backstop, the Federal Reserve.

The modern era has been defined by a recurring pattern of crisis, response, and the subsequent expansion of the state's safety net. Each crisis has been triggered by the implosion of a specific set of modern financial instruments that, at their core, performed the same function as their historical antecedents.

1987 (Black Monday): The crash was severely exacerbated by a strategy known as "portfolio insurance". This involved using computer models to automatically sell stock index futures as the market fell, in an attempt to hedge equity portfolios. This strategy was, in essence, a form of dynamic options replication. As prices dropped, the models dictated more selling, which pushed prices lower still, creating a devastating feedback loop. The Federal Reserve responded by flooding the system with liquidity to prevent a wider collapse of securities firms.

1998 (Long-Term Capital Management): The near-collapse of the hedge fund LTCM was driven by its massive, highly leveraged positions in "convergence trades". LTCM bet that the spreads between various government bonds and other securities would narrow over time. When the Russian debt default caused a global flight to quality, these spreads widened dramatically instead, wiping out the fund's capital. The fund's immense leverage, with over $1 trillion in derivatives positions on just a few billion dollars of equity, created systemic risk, forcing the Federal Reserve Bank of New York to orchestrate a private bailout by its major creditors to prevent a chain reaction of defaults.

2008 (Global Financial Crisis): The most severe crisis since the Great Depression was centered on the securitization of subprime mortgages into Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS) and Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs). This process of "collateral alchemy" transformed risky, illiquid loans into securities that were often rated AAA. These securities were then financed through the overnight repo market, creating a fatal maturity mismatch: long-term, risky assets were being funded with short-term, flight-prone cash. When housing prices fell and the underlying mortgages began to default, the value of MBS and CDOs plummeted, triggering a run in the repo market as lenders refused to roll over their loans. This led to a complete freeze in credit markets. The Federal Reserve responded by creating an "alphabet soup" of emergency lending facilities (PDCF, AMLF, TALF, etc.), effectively acting as a modern rediscount window for a vast array of non-bank entities and asset classes that had never before had direct access to the central bank.

2019-2023 (The Everything Crisis): The modern era has seen the Fed's backstop become nearly continuous. A "hiccup" in the repo market in September 2019 required large-scale bill purchases. The COVID-19 shock in March 2020 was met with "QE-Infinity"—an open-ended commitment to purchase assets in whatever quantities were needed to stabilize markets. This was followed by massive fiscal stimulus. Finally, when the Fed's own rapid interest rate hikes in 2022-2023 created huge unrealized losses on banks' "held-to-maturity" (HTM) bond portfolios, the resulting stress (epitomized by the failure of Silicon Valley Bank) was met with yet another new facility, the Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP). The BTFP allowed banks to borrow against their devalued bonds at par value, not their market value, effectively socializing the interest-rate risk the Fed itself had created.

Throughout this period, the U.S. government's war-adjacent finance—persistent defense outlays and massive support for conflicts in Ukraine and the Indo-Pacific—has continued to ride on the unparalleled depth and liquidity of the U.S. Treasury market. The cycle of petrodollar recycling continues, with foreign central banks, allied governments, and private dollar holders (such as money market funds) absorbing the vast issuance of U.S. debt needed to fund these geopolitical ambitions.

The social echo of this era of financialized capitalism and crisis management has been a dramatic rise in wealth and income inequality, which in turn has fueled periodic waves of populism on both the left and the right. The political fuel is the same as that which ignited in the aftermath of the Gründerkrach or during the Weimar Republic: a sense of a rigged system where gains are privatized and losses are socialized. The reason the system has not collapsed in the same way is the strength and scale of modern state institutions—automatic stabilizers like unemployment insurance, FDIC deposit guarantees, and, most importantly, the global financial backstop provided by the Federal Reserve's swap lines and its willingness to act as the lender of last resort to the world. The machine is larger and more robust, but it runs on the same fundamental principles.

The Contract Lens: Microstructure Vignettes

To truly grasp the unchanging nature of the financial machine, it is useful to zoom in from the macro-historical level to the microstructure of the individual transaction. The experience of the participant—the signing of a short form today in exchange for a right or an obligation tomorrow—is remarkably consistent across centuries. The complexity is hidden in the clearing and backstopping mechanisms that sit one or two levels above the transaction itself.

Berlin, 1872—A Forward on Krupp: You stand under the ornate galleries of the Berlin Börse. You find a Makler you trust and agree on the terms for a time bargain: one hundred shares of Krupp, at a price of 250 thalers per share, for settlement at the end of the month. He jots the details on a pre-printed slip, which you both sign. You then visit a clerk to post your Einschuss—a margin payment of 25 thalers per share. You walk away with a copy of the slip, holding a leveraged bet on the industrial future of the Reich. On settlement day, you will not see a single share certificate; you will simply settle the price difference in cash with your counterparty. The Reichsbank is a distant presence, its influence felt only through the discount rate that affects the general availability of credit.

Berlin, 1895—A Prämiengeschäft on Rye: You are a grain merchant concerned about falling prices before the harvest. You approach a broker on the commodity exchange and execute a Prämiengeschäft. You pay a small premium, a Prämie, for the right, but not the obligation, to sell a specified quantity of rye at today's price in three months' time. The contract is a simple, one-page form. You have just purchased a put option. You know, however, that the political winds are shifting; the powerful agrarian lobby is agitating against this "speculative" trading, and you suspect that this type of contract will soon be banned by law.

Berlin, 1916—A War Loan Subscription: You enter your local post office, where posters exhort you to "Give Gold for Iron." You subscribe to the latest Imperial War Loan (Kriegsanleihe), exchanging your savings for a government bond certificate promising a steady 5% interest. You feel a surge of patriotism. Unseen by you, the transaction sets a hidden machine in motion. Your bond certificate can now be used as collateral at a Darlehnskasse, which will issue new loan notes against it. These notes will flow to the Reichsbank, where they will be counted as reserves, allowing the central bank to print the money needed to pay for the shells being produced at the Krupp factory. Your act of saving has become the foundation for monetary expansion.

Essen, 1936—A MEFO Bill Settlement: Your factory has just delivered a shipment of shell casings to the Wehrmacht. An official from the Ministry of Economics does not hand you a check. Instead, you receive a bill of exchange, a MEFO bill, drawn on a company you have never heard of. It promises payment in six months. You take the bill to your house bank, the Deutsche Bank. They immediately discount it, crediting your account with the full amount minus a small fee. The bank is not worried; they know they can rediscount the bill at the Reichsbank at any time. The paper will be rolled over in six-month increments, perhaps for years. The rearmament is funded, your factory is paid, and the entire transaction remains invisible on the government's official budget.

Wall Street, 2006—An MBS/CDO Transaction: You are a mortgage originator. You have just bundled a thousand subprime loans into a mortgage-backed security. An investment bank buys the pool from you, combines it with dozens of similar pools, and structures a Collateralized Debt Obligation. They slice it into tranches—senior, mezzanine, equity—each with a different risk profile. A monoline insurance company writes a credit default swap on the senior AAA tranche, effectively selling a "premium" against its default. The AAA tranche is then sold to a pension fund, which finances the purchase by pledging it as collateral in the overnight repo market. The Federal Reserve is an invisible but assumed backstop for the entire financial system, the ultimate guarantor of liquidity—an assumption that will be tested to its breaking point.

Across these eras, the user experience is the same: sign a piece of paper today that represents a claim on the future. Trust that someone higher up the chain—a broker, a central bank, a sovereign—will ensure that the paper is liquid and the promise is good.

Financial “Plumbing”

The following table synthesizes the historical episodes discussed, breaking them down into their core components. It serves as an analytical matrix to demonstrate the recurring structure of the financial machine, highlighting how the same fundamental functions are performed by different instruments and institutions over time. This systematic comparison makes the "one arc" thesis tangible, showing the consistent interplay between state ambition, financial innovation, leverage, and the socialization of risk.

Table VI: A Comparative Matrix of State-Engineered Financial Cycles

Why It Repeats: The Five Invariants

The remarkable consistency of the pattern laid out in the preceding historical analysis is not a coincidence. It stems from a set of five invariant principles that govern the relationship between state power, finance, and human behavior. These principles form the core logic of the machine, ensuring that while the specific instruments and narratives change, the underlying cycle of boom, bust, and bailout repeats.

Ambition Beats Tax: The foundational driver of the cycle is the persistent gap between a state's ambitions and its willingness or ability to fund them through direct, transparent taxation. Grand projects—whether waging war (Imperial Germany, Nazi Germany), building an empire (Great Britain), managing a global hegemonic system (United States), or engineering a domestic economic rescue (post-2008)—are politically and economically expensive. Raising taxes to the required level is often politically impossible, risking public backlash and electoral defeat. Financial engineering offers a politically expedient alternative. It allows the state to mobilize vast resources today by issuing paper promises against future revenues, effectively funding its goals on credit without the immediate political pain of taxation.

Paper Multiplies Money: The core technology of the machine is the creation of financial instruments that sever the link between immediate payment and economic activity. A forward contract, a bill of exchange, an installment subscription, a Eurodollar deposit, or a repo agreement are all, at their heart, mechanisms for time-shifting purchasing power. They allow economic actors to control assets and generate activity today based on a promise to settle accounts tomorrow. This "paper" acts as a credit multiplier, creating claims and enabling transactions far in excess of the existing base money supply. The Darlehnskassenscheine and MEFO bills are the most explicit examples, where state-sanctioned paper literally becomes the reserve base for creating more money, but the principle applies to all forms of leveraged finance.