The American Endowment: Reengineering Value Investing in a Non-Zero Sum Economic Game

Cash flows are not the best measure of a "good" business, and not every dollar tomorrow is worth less than today. It ain't all the same money ya goober.

Okay so imagine this radical communist idea. We don’t maximize shareholder value. Devastating, I know.

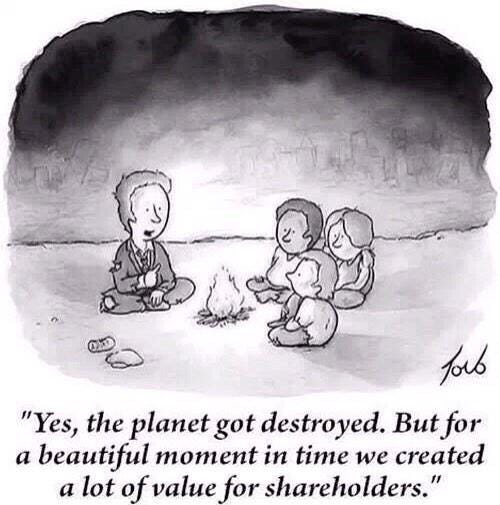

The prevailing doctrine of 20th-century finance misdefines value. It has elevated a narrow, short-sighted, and ultimately self-defeating conception of worth, one predicated on the maximization of immediate financial returns, such as free cash flow, while systematically ignoring the broader societal context in which all economic activity occurs. This conventional framework is not merely incomplete; it is actively corrosive, promoting business models that generate private profit by imposing vast, unpriced costs upon the public. The result is a system that erodes its own foundations: degrading public health, undermining civic trust, destabilizing the environment, and ultimately diminishing the long-term productive capacity of the nation.

This paper presents a necessary and radical alternative: The Doctrine of Positive Utility. This doctrine redefines the very meaning of value, shifting the focus from the extraction of short-term financial gain to the compounding creation of human flourishing, societal resilience, and collective capability. It posits that an enterprise's true worth is not its quarterly earnings but its net contribution to the aggregate well-being of society over the long term. This framework is not proposed as an ethical preference but as a logically indispensable and mathematically sound imperative for the sustainability of a complex civilization.

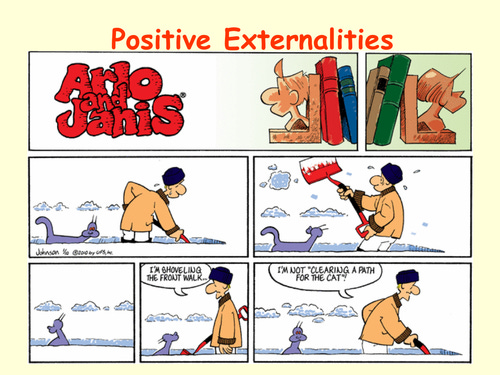

To operationalize this philosophy, I introduce a new valuation model centered on the Positive Utility Scorecard. This tool moves beyond the flawed attempt to monetize social good and instead provides a rigorous, multi-factor framework for assessing an investment's impact on core human capabilities—health, education, economic mobility, and environmental resilience, among others. By integrating this analysis with traditional financial metrics, the doctrine enables a form of accounting that prices positive utility and discounts the creation of negative societal externalities.

The American Endowment will be the first institution to be governed entirely by this doctrine. Its mission is to allocate capital not merely for financial return, but to generate a compounding societal surplus. The philosophy articulated herein is not a marketing tactic or a superficial gloss on existing paradigms. It is a foundational doctrine—a coherent set of first principles for belief and action, designed to guide the Endowment's work for generations and to offer a viable antidote to the systemic problems of debt, myopic spending, and social fragmentation that currently afflict the nation.

A New Doctrine for a New Era

This paper exists because the dominant paradigm of market capitalism is suffering a profound crisis of legitimacy. Across the political spectrum, there is a growing and justified belief that the system is failing to serve the broad interests of the public. This is not purely a failure of markets per se, but also a failure of the ideas that govern them. The crisis stems from the visible consequences of extractive business models that have been optimized to perfection under the current definition of value, and from a catastrophic, systemic failure to account for the long-horizon consequences of economic activity.1 The public’s perception of a “rigged game” is not an irrational outburst of populism; it is an intuitive and increasingly accurate diagnosis of a system that has become expert at privatizing financial gains while socializing immense, unpriced societal costs.

The Catastrophic Failure of Pricing

At the heart of this systemic dysfunction is the concept of externalities: the uncompensated impacts of one party's actions on another. In modern economics, this is often treated as a peripheral issue, a footnote in textbooks. In reality, it is the central, fatal flaw in conventional economic accounting. A negative externality occurs when a transaction between a buyer and a seller imposes a cost on a third party who is not compensated for that harm.2 A factory, for instance, can maximize its profits by polluting a river. The factory owner and the consumer of its products benefit from the transaction, but the downstream fishing community, the families whose water is contaminated, and the broader ecosystem bear the true cost. This cost—manifesting in lost livelihoods, increased healthcare expenses for conditions like asthma, and ecological collapse—is entirely absent from the factory's profit and loss statement and from the market price of its goods.2

This failure to price negative externalities is not an isolated problem; it is the fundamental logic behind many of the most pressing crises of our time. From the carbon emissions driving climate change to the social media algorithms degrading mental health, our economic system incentivizes and rewards behavior that creates immense, long-term societal liabilities because those liabilities are not on the balance sheet. This leads to a market that is not merely inefficient but actively destructive, systematically overproducing goods and services whose true social cost far exceeds their private benefit.2

What I Intend to Prove

This doctrine is offered as a direct response to this crisis. It is built upon a new conception of value, one that corrects the fundamental accounting errors of the past. Through the course of this paper, I intend to prove three core propositions that form the foundation of the American Endowment and its mission:

That only long-term positive utility investing is compatible with a functioning society. I will demonstrate that an investment framework must explicitly and rigorously account for its total impact on human well-being and societal resilience. Any doctrine that fails to do so will, by its very nature, promote extractive behavior that undermines the social, human, and natural capital upon which all economic prosperity ultimately depends.

That financial returns and societal returns are not mutually exclusive; they are causally linked. I will argue that over a sufficiently long time horizon, authentic and sustainable financial returns are a direct consequence of generating positive societal returns. A healthier, better-educated, more stable, and more resilient population is a more productive and innovative one, creating a virtuous cycle of compounding value that benefits all stakeholders, including investors.

That this is a doctrine, not a marketing tactic. The principles and frameworks outlined in this paper are not a rebranding of flawed and superficial concepts like Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) investing. What follows is a coherent and comprehensive doctrine—a set of first principles for belief and action. It is designed to be rigorous, transparent, and accountable, serving as the intellectual and operational cornerstone for a new kind of institution dedicated to the long-term flourishing of the American republic.

The Collapse of the Conventional Doctrine: An Autopsy of Extractive Value

To build a new system, one must first perform a rigorous autopsy of the old. The conventional doctrine of value, which has dominated finance and business for the better part of a century, is not merely outdated; it is founded on a set of intellectual premises that are demonstrably false and practically destructive. Its tools are precise in their calculations but profoundly inaccurate in their conception of reality, leading to a form of capitalism that systematically consumes the foundations of its own prosperity. This section deconstructs the core tenets of this doctrine, exposes its inherent flaws, and illustrates its ruinous consequences.

A. The Traditional View of Value: A Precise and Inaccurate Science

The intellectual edifice of modern investment theory rests largely on the principles of value investing, first codified by Benjamin Graham and later popularized by his most famous disciple, Warren Buffett. This school of thought brought a much-needed discipline to a field once dominated by speculation, establishing a framework for valuing a business based on its underlying economic reality rather than the fickle whims of the market.6

The core principles are, on their face, eminently sensible. Value investors are taught to view a stock not as a flickering ticker symbol but as a fractional ownership of a real business.6 They are encouraged to adopt a long-term mindset, recognizing that the market's short-term mood swings create opportunities for the patient investor.7 Graham’s famous parable of "Mr. Market"—a manic-depressive business partner who offers to buy or sell shares at wildly fluctuating prices each day—instructs the intelligent investor to ignore the noise and focus on the fundamental, or "intrinsic," value of the enterprise.9

To determine this intrinsic value, the value investor employs a set of quantitative tools. The goal is to calculate what a business is truly worth, independent of its current stock price. Key metrics include the price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio, which measures how much an investor pays for one dollar of a company's earnings, and the price-to-book (P/B) ratio, which compares the company's market price to the net value of its assets.6 The most sophisticated tool is the discounted cash flow (DCF) analysis, which attempts to calculate the present value of all the cash a business is expected to generate in the future.

The central risk management principle in this paradigm is the "margin of safety".7 After calculating a company's intrinsic value, the investor should only buy its stock at a significant discount to that value. If a business is calculated to be worth $100 per share, a value investor might only be willing to buy it at $65, creating a buffer against errors in judgment or unforeseen negative events.8 This methodical, data-driven approach promises "safety of principal and an adequate return," separating investing from mere speculation.7

B. The Shortcomings of Classical Models: Myopia and Externalities

For all its rigor, the classical doctrine of value is built upon two fundamental and crippling flaws: time-horizon myopia and the systematic ignorance of externalities. These are not separate problems but are deeply intertwined, stemming from a single root failure to define "value" in a comprehensive and realistic way. The result is a framework that is mathematically precise but conceptually blind, creating a dangerous illusion of knowledge while ignoring the most critical factors for long-term sustainability.

Time-Horizon Myopia

The first flaw is a structural inability to think in truly long-term spans. While value investors champion a "long-term horizon," the very tools they use impose a form of analytical short-sightedness. This "myopic behavior" is a well-documented cognitive and institutional bias toward immediate results that systematically undervalues distant consequences.1 Humans are psychologically wired to overvalue present rewards and discount future costs, a tendency that is amplified by the structure of modern financial markets.1 The relentless pressure of quarterly earnings reports, for example, has been empirically shown to induce managerial myopia, causing executives to cut back on long-term investments in research, development, and capital assets in order to meet short-term profit targets.11

This myopia is embedded in the DCF model itself. While theoretically projecting cash flows into perpetuity, the practical limit of a detailed DCF analysis is typically 5 to 10 years. Beyond that, future earnings are bundled into a "terminal value" calculation, which is highly sensitive to abstract assumptions about long-term growth rates. This structure inherently devalues investments whose primary payoffs occur 15, 20, or 30 years in the future. Foundational societal investments, such as universal early childhood education or preventative public health infrastructure, have enormous, well-documented long-term returns in the form of higher productivity, lower crime rates, and reduced healthcare costs. However, because these returns fall outside the conventional investor's valuation window, they are rendered effectively worthless by the standard models.12 The system is thus structurally blind to the most important investments a society can make in its own future.

The Illusion of a Closed System

The second, and related, flaw is the treatment of the corporation as a closed system, hermetically sealed from the society and environment in which it operates. The metrics of value investing—earnings, cash flows, margins—are exclusively internal to the firm. They meticulously account for the costs a company pays for its labor and materials, but they completely ignore the costs it imposes on the world around it.2

This creates a profoundly distorted picture of value. A company can report stellar cash flows while destroying a community's water supply. A social media platform can maximize user engagement and advertising revenue while fueling an epidemic of adolescent anxiety. A payday lender can boast impressive profit margins while trapping vulnerable families in inescapable cycles of debt. In the parlance of the conventional doctrine, these are not costs; they are "externalities." But they are only external to the company's flawed accounting. To society, they are very real costs, representing a massive, accumulating debt that degrades the nation's human, social, and natural capital. By failing to price these externalities, the traditional calculation of "intrinsic value" becomes a dangerous fiction, celebrating as "valuable" enterprises that are, in fact, engaged in the net destruction of societal wealth.

The core failure of modern finance is therefore not moral but epistemological. It is a failure of accounting. The system uses tools that are mathematically precise but conceptually bankrupt. It is not simply failing to price long-term, external impacts; it is incapable of pricing them within its current paradigm. This means the problem cannot be fixed by merely tweaking the models or adding a new "factor." It requires a fundamental redefinition of the "value" we are trying to measure in the first place.

C. Case Studies in Value Destruction

The theoretical flaws of the conventional doctrine are not abstract. They manifest in the real world, creating entire industries whose business models are predicated on the generation of negative societal surplus. These case studies illustrate how the pursuit of myopic, extractive value ultimately fails both society and, in the long run, the investors themselves.

Tobacco: Profitable Until It Wasn’t

The tobacco industry stands as the quintessential historical example of the conventional doctrine's failure. For most of the 20th century, tobacco companies were paragons of shareholder value. They possessed powerful brands, loyal customers, and immense pricing power, generating decades of predictable and growing cash flows. By every metric of classical value investing, they were "terrific economic castles."

However, this financial success was built on a colossal, unpriced negative externality: the devastating impact of smoking on public health. The true costs of the industry were not borne by the companies or their shareholders but by society at large. A landmark 2017 report found that the global economic burden of tobacco use exceeds $1 trillion annually in direct healthcare expenditures and lost productivity from death and disease.14 This represented a massive, accumulating societal debt. For decades, this debt was ignored by the market. Eventually, however, it came due in the form of massive litigation, sweeping government regulation, and a fundamental collapse of the industry's social license to operate. The long-term value of these once-impregnable businesses was decimated, revealing that their decades of "profit" had been, in reality, a temporary loan from the future health of society.

Payday Lending: Margin Built on Human Desperation

A more contemporary example is the payday lending industry, a business model that is structurally dependent on creating negative outcomes for its customers. While marketed as a source of short-term emergency credit, the industry's profitability is driven by trapping borrowers in cycles of debt.15 Research consistently shows that the vast majority of the industry's revenue—between 76% and 90%—comes not from one-time loans but from "loan churning," where repeat borrowers are forced to take out new loans to pay off old ones, incurring exorbitant fees at each turn.15 This business model costs American households an estimated $3.5 to $4.2 billion in excess fees each year.15

Payday lenders systematically target the most vulnerable populations, clustering their storefronts in lower-income neighborhoods and near military bases, preying on individuals with low financial literacy and few alternatives.15 The result is not a service that helps people bridge a financial gap, but a mechanism that exacerbates financial distress, leading to increased difficulty in paying for basic necessities like rent and utilities, and even higher rates of foreclosure.17 From a conventional perspective, a payday lending company might appear "valuable" due to its high profit margins. From a societal perspective, it is a purely extractive enterprise, generating financial returns by systematically destroying the financial well-being of its customers.

Social Media: Engagement at the Cost of Collective Sanity

The business model of many dominant social media platforms represents a newer, more insidious form of value extraction. These platforms generate revenue by harvesting user attention and selling it to advertisers. To maximize this revenue, their algorithms are optimized for one primary metric: user engagement. The unintended, but predictable, consequence of this optimization is the amplification of content that is emotionally activating, polarizing, and often misleading.

While the financial costs are harder to quantify than those of tobacco or payday lending, the negative externalities are vast and increasingly well-documented. They include a measurable decline in the mental health of adolescents, the erosion of shared reality and civic discourse through the creation of filter bubbles and the spread of misinformation, and the degradation of society's collective ability to focus on complex problems. These are real costs imposed on public health, social trust, and democratic stability. Under the conventional doctrine, a platform that successfully maximizes engagement at the expense of collective sanity is considered a high-value enterprise. Under a more rational accounting system, its true net value would be heavily discounted by the societal damage it creates.

D. Why This Fails Civilization

These case studies are not anomalies; they are the logical endpoint of a system that defines value too narrowly. When capital is allocated based on myopic and incomplete metrics, it naturally flows toward business models that are extractive. The pursuit of this false value creates a series of vicious, negative feedback loops that are corrosive to a functioning civilization.

First, the negative externalities generated by extractive industries degrade the nation's stock of human and natural capital. Pollution sickens the workforce, predatory financial products impoverish communities, and addictive technologies diminish cognitive capacity. Second, this degradation of human capital reduces the overall productivity and innovative potential of the economy, shrinking the pie for everyone. Third, the resulting economic stagnation and rising inequality erode social trust, the invisible infrastructure that makes complex market economies possible. Without trust, transaction costs rise, cooperation breaks down, and political instability increases.

The conventional doctrine of value, therefore, contains the seeds of its own destruction. It is a system that, in its relentless pursuit of short-term, isolated profit, systematically undermines the very conditions required for long-term, shared prosperity. It is, in the final analysis, unsustainable.

Table 1: The Collapse of Conventional Value Metrics vs. The Positive Utility Doctrine

The First Principles of Long-Term Sustainable Value

Having deconstructed the flawed logic of the conventional doctrine, I now turn to the construction of a new one. The Doctrine of Positive Utility is not built on abstract ideals but on a set of rigorous first principles that provide a more accurate and durable foundation for assessing value. These principles redefine the purpose of investment, the nature of capital, and the time horizon required for rational analysis. They form the philosophical bedrock upon which the American Endowment's entire strategy is built.

A. Value is a Function of Net Surplus Creation

The first principle of this doctrine is a fundamental redefinition of what constitutes a "valuable" enterprise. In the conventional paradigm, value is synonymous with profit—the financial surplus that accrues to shareholders. This is a dangerously incomplete definition.

I assert that true value is a function of Net Surplus Creation. Net Surplus is defined as the total positive value an organization creates for all of its stakeholders minus the total costs it imposes upon them. Stakeholders are not limited to shareholders but include customers, employees, suppliers, the broader community, and the natural environment. The "value" created is not just financial; it encompasses improvements in health, knowledge, well-being, and opportunity. The "costs" imposed are not just monetary; they include all negative externalities, such as environmental degradation, the erosion of social trust, or the promotion of unhealthy behaviors.

Under this principle, an enterprise is only truly valuable if it leaves the world, in aggregate, better off than it found it. A company that generates $1 billion in profit for its shareholders but imposes $2 billion in unpriced healthcare and environmental cleanup costs on society is not a value creator; it is a value destroyer. It has generated a net deficit, and its activities make society poorer, not richer. Conversely, an enterprise that develops a technology that dramatically improves literacy may generate modest profits but create immense societal surplus in the form of a more capable and productive citizenry. This enterprise is a true value creator. The goal of the Endowment is to identify and fund these net surplus creators.

B. All Value Is Time-Horizon Dependent

The second principle is that value is inextricably linked to the time horizon over which it is measured. The conventional doctrine's myopia, driven by quarterly reporting cycles and short-term investor sentiment, is a recipe for irrational decision-making. It is an invitation to be fooled by what Benjamin Graham called "Mr. Market," the moody and unreliable arbiter of daily prices.9

I mandate a minimum analytical time horizon of 10 to 20 years. This is not an arbitrary preference; it is a logical necessity for several reasons. First, it allows the signal of fundamental value creation to emerge from the noise of short-term market volatility. Second, it is the only timeframe over which the true, compounding effects of foundational investments can be observed. The benefits of improved education, preventative healthcare, or sustainable infrastructure do not manifest in a single quarter; they unfold over decades, building on themselves in a virtuous cycle. Third, a long time horizon is necessary to properly account for the accumulation of negative externalities. The costs of climate change or chronic disease are not acute, one-time events; they are slow-moving crises that build over generations. Any analysis with a shorter horizon will systematically underestimate these catastrophic tail risks. By adopting a multi-decade perspective, I align our investment strategy with the actual timescale of civilizational progress and decline.

C. The Law of Compounding Capability

The intellectual core of the Doctrine of Positive Utility is the Law of Compounding Capability. This principle reframes our understanding of the ultimate source of economic value. It moves beyond the traditional factors of production—land, labor, and physical capital—to identify the true engine of sustainable prosperity: human capability.

This principle is grounded in the Nobel Prize-winning work of economist Amartya Sen, whose Capability Approach provides a revolutionary framework for understanding well-being and development.18 Sen argued that the goal of economic development should not be the mere accumulation of resources, like increasing GDP per capita, but rather the expansion of people's real freedoms and opportunities—their

capabilities to "do and be" the things they have reason to value.20 A person's well-being is best measured not by what they

have (income, commodities), but by what they are actually able to do (be healthy, be educated, participate in civic life).18

The Doctrine of Positive Utility takes this philosophical insight and transforms it into an economic law. I posit that human capability is the ultimate form of capital. Unlike physical capital (like a factory or a machine) which depreciates over time, human capability—when nurtured—compounds. A healthy, well-educated, and civically engaged population is not just a moral good; it is the most powerful economic asset a society can possess. Healthier people are more productive and live longer, contributing more to the economy over their lifetimes. Better-educated people are more innovative, adaptable, and capable of solving complex problems. A society with high levels of social trust and stability has lower transaction costs and is more resilient in the face of crises.

Therefore, investments in foundational human capabilities—in public health, in universal literacy and numeracy, in civic institutions that build trust—are not "social spending" or "costs" to be minimized. They are the highest-return capital expenditures a society can make. They generate a multiplier effect, creating a virtuous cycle where increased capability leads to greater economic output, which in turn provides more resources to further invest in capability. This compounding of human potential is the ultimate driver of long-term, sustainable value creation.23 This reframes the entire national budget debate. Spending on education is no longer a line-item expense; it is an investment in the core productive engine of the economy, with a long-term ROI that is likely to dwarf that of a new factory or a short-term tax cut.

D. The Moral and Mathematical Mandate

The final principle synthesizes the preceding arguments and frames the Doctrine of Positive Utility as a survival imperative. The choice to adopt this framework is not an "ethical" choice in opposition to a "financial" one. It is the only logically coherent and mathematically sound choice for ensuring the long-term viability of a complex society.

A system that defines value in a way that encourages the net destruction of its own capital base is, by definition, unsustainable. A society that systematically degrades the health of its people, the education of its children, the stability of its environment, and the trust in its institutions is engaging in a form of slow-motion suicide. It is drawing down its core assets to fund short-term consumption. The eventual result is systemic collapse.

Therefore, the mandate to invest for positive utility is both moral and mathematical. It is moral because it aligns the allocation of capital with the goal of human flourishing, recognizing the inherent dignity and potential of every individual. It is mathematical because it is based on a corrected form of accounting that recognizes the compounding nature of human capability and the catastrophic, accumulating costs of negative externalities. A system that consistently generates a net surplus of human capability is one that will grow, adapt, and thrive. A system that consistently generates a net deficit is one that is doomed to fail. The Doctrine of Positive Utility is thus not a preference; it is a prerequisite for a sustainable civilization.

The Positive Utility Framework

A philosophy, no matter how compelling, is inert without a practical method of application. The Positive Utility Framework is the engine that translates the doctrine's first principles into a concrete, rigorous, and repeatable process for investment analysis and decision-making. It is designed to overcome the critical flaws of existing "socially conscious" investment models by providing a transparent, philosophically grounded, and auditable system for measuring what truly matters. This framework does not seek to replace financial analysis but to augment and correct it, ensuring that capital is allocated not just to enterprises that are profitable, but to those that are genuinely generative.

A. Definition

The central concept of the framework is "Positive Utility." I define Positive Utility as any measurable impact of an enterprise's activities that verifiably increases human capability, health, dignity, and resilience. Conversely, Negative Utility is any impact that diminishes these qualities.

This definition is deliberately broad and is directly derived from the philosophical architecture of Amartya Sen and Martha Nussbaum. It moves beyond simplistic metrics like carbon emissions or diversity statistics to capture a more holistic understanding of an organization's role in society.

The key is that utility is measured in terms of its effect on people's real opportunities to live flourishing lives.20 An action has positive utility if it expands the set of valuable "beings and doings" available to individuals, such as the capability to be healthy, to be well-educated, or to participate freely in the life of one's community.18

B. The Positive Utility Scorecard

The primary tool for implementing this framework is the Positive Utility Scorecard. This scorecard is designed to avoid the critical error of false monetization inherent in frameworks like Social Return on Investment (SROI). SROI attempts to assign a financial proxy to every social outcome, a process that is notoriously subjective, complex, and susceptible to manipulation.26 What, after all, is the "correct" dollar value of a child's increased self-esteem or a community's renewed sense of trust? Such calculations are arbitrary and create a misleading sense of precision.

The Positive Utility Scorecard takes a different, more intellectually honest approach. It does not attempt to monetize incommensurable values. Instead, it uses a multi-factor scoring system to assess an enterprise's contribution to a set of fundamental human capabilities. The categories for this scorecard are explicitly and transparently based on philosopher Martha Nussbaum's list of ten "Central Human Capabilities," which provides a comprehensive, cross-culturally resonant, and philosophically robust account of the essential components of a life worthy of human dignity.27

The scorecard categories are as follows:

Life & Bodily Health: Assesses impacts on longevity, physical health, reproductive health, nutrition, and access to adequate shelter. A pharmaceutical company developing a life-saving vaccine would score positively; a food company marketing unhealthy products to children would score negatively.

Bodily Integrity: Measures contributions to physical safety and freedom of movement. A company with an exemplary worker safety record would score positively; a company whose products are linked to violence would score negatively.

Senses, Imagination & Thought: Evaluates impacts on education, access to information, critical thinking skills, and freedom of expression. An EdTech platform that demonstrably improves literacy and numeracy would score highly 32; a media company that profits from spreading disinformation would score poorly.

Emotions: Assesses impacts on mental and emotional well-being. A company that provides robust mental health support for its employees would score positively; a social media company whose product design is shown to be addictive and anxiety-inducing would score negatively.

Practical Reason: Measures contributions to individuals' ability to form a conception of the good and plan their lives. This includes promoting financial literacy and providing stable, predictable employment. Predatory lenders that undermine financial planning would score very negatively here.16

Affiliation & Civic Competence: Evaluates impacts on social connection, community trust, and the capacity for civic participation. A company that fosters strong community bonds would score positively; a company with a history of discriminatory practices that erode social cohesion would score negatively.

Relationship with Other Species & Environmental Resilience: Assesses the enterprise's impact on the natural world. This includes pollution, resource depletion, and contributions to climate change. A company developing breakthrough technology for carbon capture would score positively; a company with a record of environmental disasters would score negatively.

Play & Recreation: Measures contributions to work-life balance and access to leisure and recreational activities.

Control Over One's Environment: This capability has two components:

Political: Impact on the ability of individuals to participate in political choices that govern their lives.

Material: Impact on economic mobility, the right to seek fair employment, and control over one's property and labor. A company with strong labor practices and pathways for advancement would score positively; a company that relies on exploitative labor practices would score negatively.

C. Application in Investment Analysis

The Positive Utility Scorecard is not a replacement for rigorous financial analysis; it is a crucial, corrective lens through which financial data is viewed. The process works as follows:

Scoring: Each potential investment is analyzed and scored across the nine capability categories, typically on a scale (e.g., -5 to +5). This analysis is based on verifiable, objective data, not on corporate marketing materials.

Aggregation: The individual scores are aggregated into a single, weighted "Positive Utility Score." The weighting can be adjusted based on the Endowment's specific strategic priorities at a given time.

Integration: This score is then used as a primary factor alongside traditional financial projections (e.g., DCF analysis, market position, management quality). It is a qualitative and quantitative overlay that provides a more complete picture of the investment's true, long-term value.

Discounting Negative Utility: The framework's most powerful feature is its treatment of negative utility. Any company that generates a significant negative score in a critical area (such as Health, Bodily Integrity, or Control Over One's Environment) will have its valuation heavily discounted or be excluded from the investment universe entirely, regardless of its projected financial margins. This mechanism effectively internalizes the cost of negative externalities, forcing the valuation to reflect the company's true societal impact. This approach is more robust than simple exclusion lists because it is dynamic and based on a holistic analysis rather than a static category.

D. How to Publish and Audit It

The credibility of this framework rests on a commitment to radical transparency, which stands in stark contrast to the opaque and often misleading world of ESG and impact investing.33 The American Endowment will be bound by a public

Transparency Covenant with the following commitments:

Quarterly Transparency Reports: Each quarter, the Endowment will publish a full report detailing not only its financial performance but also the complete Positive Utility Scorecard for every single holding in its portfolio. This goes far beyond the standard practice of simply listing top ten holdings.35

Public Rationale for Every Investment: Every significant investment decision (buy, sell, or material change in position) will be accompanied by a publicly released memorandum. This document will provide a plain-English rationale explaining how the decision aligns with the Doctrine of Positive Utility, detailing the key factors in both the financial and utility analysis.

Independent Audits: The Endowment's financial statements and its Positive Utility scoring process will be subject to an annual, independent audit by a reputable third party. The full audit report will be made public.

This system creates a powerful feedback loop. By operating in the open, the Endowment invites scrutiny, critique, and collaboration, ensuring that its methods are constantly refined and that its commitment to its founding doctrine remains unshakable. It is a tool for judgment, not a substitute for it, and its integrity is guaranteed by its transparency.

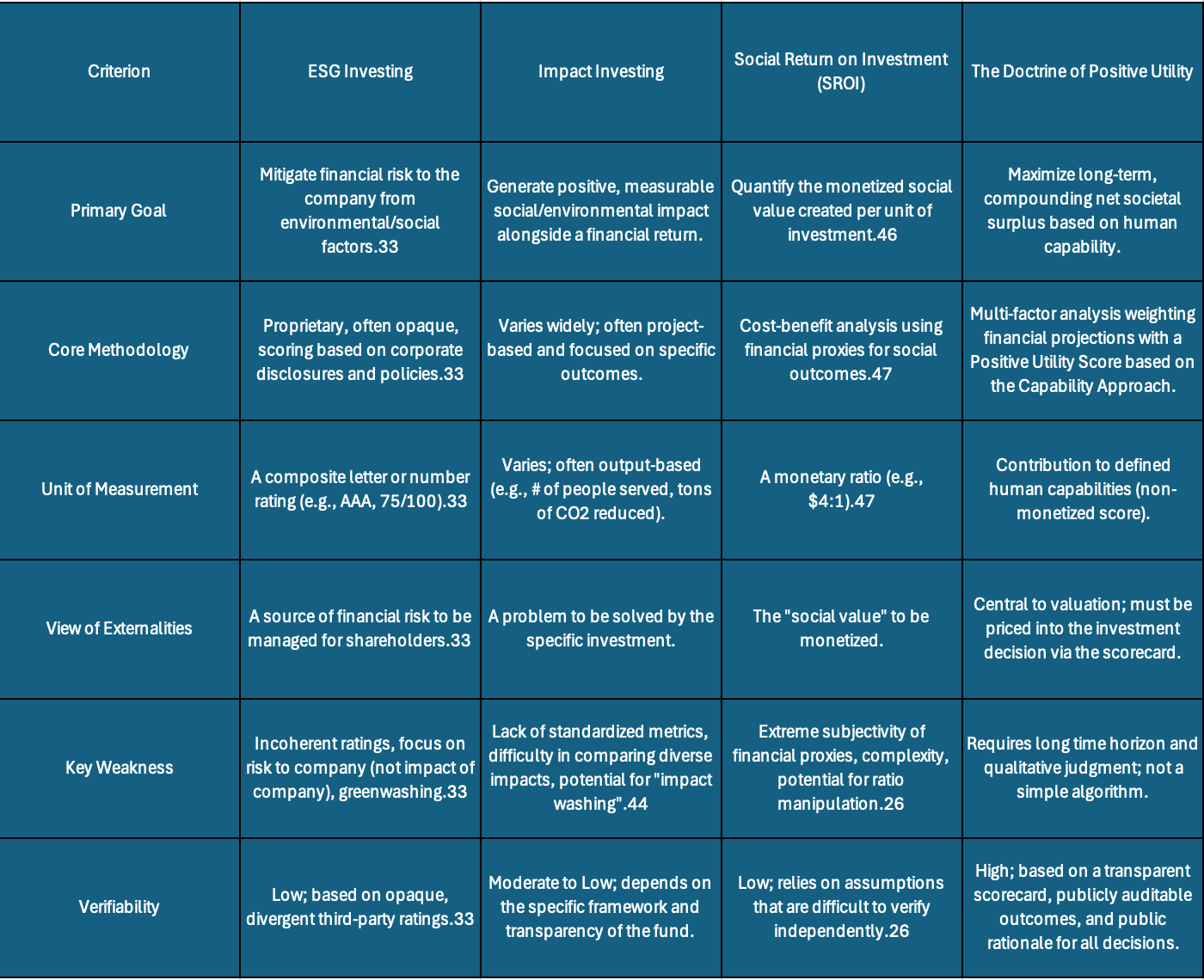

A Superior Doctrine

The Doctrine of Positive Utility is not proposed in a vacuum. It enters an intellectual marketplace crowded with competing theories of investment and social value. To establish its unique merit, it is essential to conduct a rigorous comparative analysis, demonstrating how our doctrine overcomes the specific, well-documented failings of its predecessors. This is not an exercise in academic differentiation but a necessary argument to prove that the Positive Utility Framework is not merely different, but superior—more coherent, more robust, and more effective at achieving its stated goals.

A. Efficient Market Hypothesis

The Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH), in its various forms, posits that asset prices fully reflect all available information.37 Proponents of EMH argue that it is therefore impossible to consistently "beat the market" through stock selection or timing, as any new information is instantly incorporated into prices.39 From this perspective, the best strategy is passive index investing.38

The Doctrine of Positive Utility does not fundamentally seek to "beat the market" as defined by EMH. Instead, it challenges the hypothesis's core premise by revealing the market to be systematically incomplete. EMH assumes that the "information" being priced is comprehensive. Our doctrine demonstrates that a vast and critically important category of information—namely, the true cost of negative externalities and the true long-term value of positive externalities—is systematically unavailable to the market's pricing mechanism.2

A company's stock price may efficiently reflect all publicly reported financial data, but it cannot reflect the cost of the river it is polluting or the value of the public health it is improving, because those items are not on its balance sheet. Therefore, the market is "efficient" only within a dangerously narrow and flawed information set. Our doctrine does not attempt to find pricing inefficiencies within the existing model; it seeks to correct the model itself by incorporating the missing information. We are not trying to outsmart Mr. Market; we are trying to give him a more accurate set of accounting books.

B. Factor Investing and Quantitative Models

In recent decades, quantitative investing has sought to identify specific "factors"—such as Value, Growth, Momentum, or Quality—that have historically been associated with excess returns. Portfolios are then constructed to tilt towards these factors.

It would be a profound error to view Positive Utility as just another factor to be added to this list. Factors are, by their nature, statistical correlations identified through backward-looking data analysis (backtesting). There is often no deep causal theory explaining why a factor works, only that it has worked in the past.

Positive Utility is fundamentally different. It is not a statistical correlation; it is a causal and philosophical redefinition of value itself. It is an act of first-principles accounting, not data mining. Its foundation is a normative claim about what constitutes true wealth—the expansion of human capability. The Positive Utility Scorecard is not designed to find a statistical anomaly that can be exploited for alpha. It is designed to provide a more accurate measure of an enterprise's total, long-term impact, under the theory that generative enterprises are the only ones capable of producing sustainable returns over a civilizational time horizon. It is an accounting correction, not a quantitative trading signal.

C. ESG and Impact Investing: A Critique of the Status Quo

The most prominent contemporary attempts to integrate non-financial considerations into investing are Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) and Impact Investing. While born from good intentions, these movements are plagued by deep methodological and conceptual flaws that render them ineffective at best and misleading at worst. The Doctrine of Positive Utility was specifically designed to remedy these failures.

The critique of ESG is sharp and well-documented:

Incoherent Ratings: The data shows that ESG ratings from different providers have remarkably low correlations with one another.33 A company rated highly by one agency may be rated poorly by another. This divergence suggests that the raters are either measuring entirely different things, using flawed methodologies, or that the ratings are simply "noisy" and unreliable.33 This makes it impossible for an investor to get a clear signal of a company's true ESG performance.

A Fundamental Misunderstanding of Impact: The most damning critique is that most major ESG rating systems do not measure a company's impact on the world. Instead, they measure the potential financial risk of the world to the company's bottom line.33 For example, an oil company might receive a high ESG rating not because it is reducing emissions, but because it has strong governance policies to manage the financial risks of future climate regulations. This is the precise opposite of what most retail investors believe they are buying. It is a framework for protecting shareholder value from social and environmental risks, not for generating positive social and environmental outcomes.

"Impact Washing" and Lack of Verifiability: The absence of standardized, transparent, and auditable metrics has created a fertile ground for "impact washing" or "greenwashing".42 Companies and fund managers can make vague claims about their positive impact without being held to account. Impact Investing frameworks often suffer from a similar lack of rigor, focusing on narrative and intent rather than verifiable, systemic change.44 Methodologies like SROI, which attempt to quantify impact, are criticized for their complexity, subjectivity, and susceptibility to bias, often producing a single, impressive-looking ratio that obscures more than it reveals.26

The Doctrine of Positive Utility provides a direct solution to each of these problems. It replaces the incoherent noise of ESG ratings with a single, transparent, and philosophically grounded framework: the Positive Utility Scorecard. It corrects the fundamental error of ESG's focus by measuring the company's net impact on society, not the other way around. And it combats impact washing with a radical commitment to transparency, requiring public disclosure of the full scorecard and a detailed rationale for every investment decision.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Social Investment Frameworks

D. Classical Value Investing: From Moat to Surplus

Finally, we must position our doctrine in relation to its intellectual ancestor, classical value investing. We hold great respect for the discipline and long-term orientation that Graham and Buffett brought to the field. Our doctrine does not discard their wisdom; it builds upon it and expands its scope.

Warren Buffett's central metaphor is the "economic moat"—a durable competitive advantage that protects a company's profits from competitors, like a moat protecting a castle.49 A strong brand, a low-cost production process, or a network effect are all types of moats that allow a company to maintain high returns on capital over time.

This is a powerful but ultimately defensive concept. The goal is to find and own an impregnable castle and defend it from invaders. The Doctrine of Positive Utility introduces a new, more ambitious logic: the logic of surplus. Our goal is not merely to find the strongest castle, but to invest in the activities that make the entire surrounding territory more fertile, stable, and prosperous.

A company that generates immense positive utility—for example, by creating a technology that radically improves public health or democratizes education—is doing more than just building a moat for itself. It is upgrading the human capital of the entire system. It is creating a healthier, smarter, more capable population. This, in turn, creates a more vibrant and resilient economy, expanding the total market and creating the conditions for many castles to thrive. The company that generates this surplus will undoubtedly benefit, but its greatest contribution is to the system as a whole. Our doctrine seeks to shift the focus of capital allocation from the defensive logic of the moat to the generative logic of the surplus. In the long run, the most valuable enterprise will not be the one with the widest moat, but the one that creates the most fertile ground beyond its walls.

The Doctrine in Practice: Portfolio Construction

A doctrine is only as strong as its application. The principles of Positive Utility are not abstract ideals; they are a set of clear and binding rules for the practical management of the American Endowment's portfolio. This section translates the philosophical framework into a concrete methodology for capital allocation, defining what we will and will not own, and how the portfolio will be structured to achieve its dual mandate of financial sustainability and societal surplus creation.

A. Mandated Exclusions

The first and most direct application of the Positive Utility Framework is the mandated exclusion of industries whose business models are fundamentally extractive and generate significant negative utility. These exclusions are not based on arbitrary moral preferences or popular sentiment. They are the logical consequence of applying the Positive Utility Scorecard. An industry is excluded if its core operations inherently and systematically diminish human capability, health, dignity, or resilience, resulting in a deeply negative score on one or more of the central capabilities. This approach aligns with the practice of many ethical funds that use negative screening, but our justification is rooted in our specific, transparent framework.34

The following categories of enterprise are, by their nature, incompatible with the Doctrine of Positive Utility and will be excluded from the Endowment's portfolio:

Predatory Lending: This includes payday lenders and other high-cost credit providers whose business model relies on trapping vulnerable individuals in cycles of debt. Such enterprises score profoundly negatively on the "Control Over One's Environment (Material)" and "Practical Reason" capabilities by eroding financial stability and the ability to plan for the future.15

Gambling: Enterprises whose primary revenue is derived from gambling activities. These businesses are linked to addiction, financial ruin, and significant social costs, scoring negatively on "Emotional Wellbeing" and "Control Over One's Environment (Material)".51

Addictive Attention Harvesting: This refers to social media and technology platforms whose core business model is demonstrably based on using manipulative design techniques to foster behavioral addiction for the purpose of maximizing advertising revenue. These score negatively on "Emotions" (due to links with anxiety and depression) and "Senses, Imagination & Thought" (by degrading the capacity for deep focus).

Monetized Outrage: Media enterprises whose business model relies on the algorithmic amplification of polarization, anger, and disinformation to drive engagement. These entities erode the foundations of civic discourse and social trust, scoring negatively on the "Affiliation & Civic Competence" capability.

Tobacco/Alcohol: Producers and primary distributors of tobacco and alcohol products. The immense negative impact on the "Life & Bodily Health" capability is undisputed and serves as a classic example of a negative utility enterprise.14

For-Profit Prisons: Companies that operate private correctional facilities. Their business model creates a perverse incentive to maximize incarceration, which is in direct conflict with societal goals of rehabilitation and justice.

B. Mandated Priorities

The Endowment's strategy is not merely passive and exclusionary; it is proactive and generative. I will actively seek out and prioritize investments in enterprises that score highly on the Positive Utility Scorecard, tilting the portfolio decisively towards companies and projects that are building a healthier, smarter, and more resilient society. The goal is to use capital as a tool to accelerate the development of solutions to our most pressing challenges.

Priority investment areas include:

Healthtech Focused on Prevention and Longevity: We will prioritize companies developing technologies and services that shift the healthcare paradigm from expensive, reactive treatment to cost-effective, proactive prevention. This includes innovations in diagnostics, preventative medicine, wellness platforms, and technologies that extend healthy lifespan, all of which score highly on "Life & Bodily Health."

EdTech that Democratizes Literacy and Numeracy: We will invest in enterprises that provide scalable, effective, and accessible tools for improving foundational skills in reading, writing, mathematics, and critical thinking, especially for underserved populations. Such investments directly build the "Senses, Imagination & Thought" capability, which is the bedrock of a productive workforce and an informed citizenry.

Civic Technology to Rebuild Trust and Participation: We will seek out ventures that are creating new platforms and tools to enhance civic engagement, promote constructive public discourse, increase government transparency, and rebuild social trust. These investments are critical for strengthening the "Affiliation & Civic Competence" capability.

Resilience Infrastructure: This includes investments in both physical and social infrastructure that enhance our society's ability to withstand shocks. Examples include renewable energy projects, sustainable water systems, resilient food supply chains, and community-based social support networks. These score highly on "Environmental Resilience" and "Bodily Integrity."

C. Portfolio Construction

The principles of the doctrine are embedded directly into the rules of portfolio construction, ensuring that the Endowment's assets are managed in strict alignment with its mission over the long term.

Minimum Holding Periods: To systematically combat the market's inherent short-termism, a mandatory minimum holding period will be instituted for the majority of the Endowment's equity investments. A typical minimum will be five to seven years. This rule forces a long-term perspective in analysis and prevents the portfolio from being churned based on short-term market noise. It aligns the Endowment's capital with the multi-decade time horizon required for true value creation.

Diversification Across Utility Categories: Traditional diversification focuses on spreading risk across asset classes, sectors, and geographies. The Endowment will add a new layer of diversification: across the Positive Utility categories. The portfolio will be managed to ensure a balanced contribution to all nine of the central capabilities. This prevents an over-concentration in one area of social good (e.g., only environmental technologies) and ensures the Endowment is fostering a holistic vision of human flourishing.

Capital Allocation Thresholds: The portfolio will be governed by strict allocation rules based on the Positive Utility Score. For example:

A minimum of 75% of the portfolio's assets must be invested in enterprises with a demonstrably net positive utility score.

No more than 5% of assets may be allocated to companies with a neutral score (i.e., those with no significant positive or negative impact).

Companies with a net negative utility score are ineligible for investment, reinforcing the mandated exclusions.

These rules ensure that the Doctrine of Positive Utility is not merely a philosophical statement but a binding operational constraint that guides every dollar of capital allocated by the American Endowment.

The Educational Mission: Building the Next Generation

The Doctrine of Positive Utility is more than an investment strategy; it is a new way of thinking about the relationship between capital, society, and human progress. For this idea to take root and flourish, it cannot be confined to the walls of the American Endowment. Its long-term success and perpetuation depend on a robust and multifaceted educational mission designed to cultivate a new generation of investors, economists, policymakers, and citizens who understand and can apply its principles. The Endowment will therefore be as much a teaching institution as it is an investment vehicle.

A. Teaching the Doctrine

The Endowment will dedicate significant resources to disseminating its philosophy and methodology through a variety of channels, targeting different audiences from specialists to the general public.

Fellowship Programs: The cornerstone of our educational mission will be the American Endowment Fellows Program. This will be a prestigious, fully-funded fellowship for a select cohort of early-career analysts, economists, portfolio managers, and social scientists. Modeled on successful innovation fellowships that aim to translate breakthroughs into practice 53, our program will provide intensive, hands-on training in the theory and application of Positive Utility Investing. Fellows will work alongside the Endowment's investment team, conduct original research, and develop new applications for the framework. The goal is to create an elite cadre of professionals who will go on to lead other institutions and embed the doctrine throughout the financial industry.

Partnerships with Universities and Civic Institutions: I will actively seek partnerships with leading universities and academic institutions. This will involve co-developing curricula for business, economics, and public policy schools that present the Doctrine of Positive Utility as a serious alternative to conventional theories.55 I will fund endowed professorships and research centers dedicated to the study of long-term value creation and the economics of human flourishing. By integrating our ideas into the core of academic discourse, we can influence the intellectual formation of future leaders.

Online Courses and Public Education: To build a broad base of understanding and support, the Endowment will create a suite of high-quality, publicly accessible educational materials. This will include online courses that explain the principles of the doctrine in plain English, interactive tools that allow users to apply a simplified version of the Positive Utility Scorecard, and publications that translate our research into accessible formats for policymakers and the general public.

B. Building the Next Generation of Value Investors

Beyond general education, I will create specific programs and credentials to build a recognized and respected community of practice around the doctrine.

Certifications: The Endowment will establish a formal certification process for financial professionals who demonstrate mastery of the Positive Utility Framework. Earning the "Certified Positive Utility Analyst" (CPUA) designation will signify a rigorous understanding of the doctrine and the ability to apply it in practice. This will create a clear standard of expertise in the field, distinguishing our trained professionals from those making vague ESG claims.

Case Study Competitions: I will sponsor and host annual case study competitions at top business and public policy schools across the country. Teams of students will be presented with real-world investment challenges and tasked with developing a solution using the Positive Utility Framework. These competitions will serve as a powerful teaching tool and a recruiting pipeline for our fellowship program and affiliated organizations.

Research Grants: The Endowment will establish a significant grant-making program to fund independent academic research that explores, critiques, and refines the Doctrine of Positive Utility. I welcome rigorous intellectual challenge and believe that the doctrine will only be strengthened through open debate and empirical testing. Grants will be awarded for research into topics such as improving the measurement of specific capabilities, analyzing the long-term performance of positive utility portfolios, and exploring the second-order effects of generative investments on economic growth.

Through this comprehensive educational mission, I aim to do more than just manage a successful endowment. I aim to change the conversation about value itself, building an intellectual and professional movement capable of reorienting capital towards the long-term project of human flourishing.

Governance and Accountability: A Structure Built on Trust

The ambition of the American Endowment requires an institutional structure of unparalleled integrity and resilience. A doctrine centered on long-term societal good cannot be housed within a conventional corporate structure susceptible to short-term pressures, mission drift, or co-option. The governance framework detailed here is designed to be a fortress, legally and ethically engineered to protect the Endowment's founding principles in perpetuity. It is built on a foundation of radical transparency, a redefined concept of fiduciary duty, and a clear separation of powers to ensure both patient capital allocation and effective advocacy.

A. The Dual-Entity Structure and Transparency Covenant

To achieve its goals, the enterprise will be organized as two affiliated but legally distinct non-profit entities. This dual structure is not a matter of convenience; it is the institutional manifestation of the doctrine's dual strategy of patient investment and active advocacy, carefully designed to comply with U.S. non-profit law.

The American Endowment (a 501(c)(3) Public Charity): This entity is the heart of the enterprise. Its legal purpose is charitable and educational. It will house the investment portfolio and will be solely responsible for managing it according to the Doctrine of Positive Utility. All of its activities will be strictly non-partisan. Its functions will include conducting and publishing research, running the educational fellowship programs, and pursuing long-term capital growth through generative investments.56 As a 501(c)(3), donations to the Endowment will be tax-deductible. It is absolutely prohibited from engaging in partisan political activity and can only engage in an "insubstantial" amount of lobbying.57

The American Doctrine Party (a 501(c)(4) Social Welfare Organization): This entity is the public voice of the movement. Its legal purpose is to promote social welfare. It is responsible for advocacy, public education, and perpetuating the doctrine's message in the political sphere. A 501(c)(4) is permitted to engage in significant lobbying efforts and limited partisan political activity, as long as such activity is not its primary purpose.57 Donations to this entity are not tax-deductible.

This structure creates a powerful symbiotic relationship. The 501(c)(3) Endowment acts as the patient, long-term economic engine. A portion of the investment income generated by the Endowment can be legally granted to the affiliated 501(c)(4) to fund its advocacy work. The 501(c)(4) then uses these resources to advocate for public policies—such as a carbon tax, increased funding for early education, or financial regulations that curb predatory lending—that align the "rules of the game" with the principles of the doctrine. This, in turn, creates a more favorable economic environment for the Endowment's own investment strategy.

To maintain legal integrity, strict "firewalls" must be maintained between the two entities. They must have separate boards, maintain separate books and records, and any shared resources (like office space or staff time) must be paid for by the 501(c)(4) at fair market value.59 There can be no coordination of specific political strategies between the two.

Table 3: Governance and Activity Matrix for 501(c)(3) Endowment and 501(c)(4) Political Organization

Both organizations will be bound by a Transparency Covenant, a public pledge to operate with a level of openness far exceeding legal requirements. This includes publishing monthly portfolio holdings, quarterly utility scorecards, and annual, plain-English audited reports that detail both financial performance and progress on the utility metrics.35

B. Fiduciary Charter

The board members of a non-profit endowment have three fundamental fiduciary duties: the Duty of Care, the Duty of Loyalty, and the Duty of Obedience.61 The Endowment's Fiduciary Charter will codify these duties with a unique and powerful interpretation that legally binds the board to the founding doctrine.

Duty of Care: This requires board members to act with the diligence and prudence of a reasonable person in a similar position. For the Endowment, this means staying informed not just about the financial health of the organization, but also about the principles and application of the Doctrine of Positive Utility. It requires active oversight of the investment process to ensure it adheres to the doctrine.61

Duty of Loyalty: This requires board members to act solely in the best interests of the organization and its mission, avoiding all conflicts of interest. Any potential conflict must be disclosed, and the conflicted member must recuse themselves from relevant decisions. This duty is absolute and ensures that decisions are made for the benefit of the mission, not for personal enrichment.62

Duty of Obedience: This is the critical, redefined duty that serves as the legal anchor of the entire enterprise. Typically, this duty requires the board to be obedient to the organization's mission and bylaws, as well as to the law.61 In our Fiduciary Charter, the mission of the Endowment will be explicitly and irrevocably defined as the implementation of the

Doctrine of Positive Utility. Therefore, the board's primary fiduciary obligation is to ensure that capital is allocated according to this specific framework. They are legally bound to prioritize the generation of positive utility, not merely to maximize financial returns in a vacuum. This provides a powerful legal defense against future mission drift, preventing a future board from abandoning the founding principles in favor of conventional profit-maximization.

C. Succession Planning and Anti-Co-option

An institution designed to last for centuries must be resilient against the inevitable changes in leadership and the constant pressures of the outside world. The governance structure will include robust mechanisms for succession planning and defense against co-option.

Leadership Pipelines: The fellowship programs and university partnerships are not just educational; they are the primary mechanism for identifying and cultivating the next generation of leadership for the Endowment and its affiliated entities. This ensures a continuous supply of talent that is deeply steeped in the organization's founding principles.

Redundancy Charter: The bylaws will include a "Redundancy Charter" with specific provisions designed to protect the core doctrine. For example, any proposed change to the Fiduciary Charter or the fundamental principles of the Doctrine of Positive Utility might require a supermajority vote (e.g., 90%) of the board and perhaps even the consent of a separate, independent board of doctrinal guardians. This makes it exceptionally difficult for any single generation of leaders to dilute or abandon the mission.

This governance structure is designed to create an institution that is both effective in the present and durable for the future. It is a framework built on trust, but reinforced by law, transparency, and a clear-eyed understanding of the forces that can lead even the most well-intentioned organizations astray.

The Future We Intend to Build

The Doctrine of Positive Utility is, in the final analysis, more than a set of principles for investing. It is a blueprint for a different kind of economy and a more hopeful future. It is an argument that the logic of extraction and short-term gain that has dominated our recent history is not an immutable law of nature, but a choice—and that we can, and must, choose differently.

Imagine an economy where the most brilliant minds and the largest pools of capital are not drawn to creating the next addictive social media app or the next complex derivative, but are instead competing to solve the most fundamental challenges of human well-being. Imagine a market where the "most valuable" companies are not those with the highest profit margins, but those that make the greatest net contribution to public health, to the education of our children, and to the resilience of our communities and our planet. This is not a utopian fantasy; it is the logical outcome of a system that correctly defines and measures value.

When we align the allocation of capital with the creation of human flourishing, we unleash the most powerful force for progress known to humanity: the compounding of human capability. A society that invests in the health, knowledge, and stability of its people is a society that is investing in its own capacity for innovation, productivity, and resilience. The financial returns generated by such a system are not a happy byproduct; they are the natural and inevitable result of creating a more capable and prosperous society.

The stewards of capital—the managers of endowments, pension funds, and great fortunes—hold a unique and profound power. They sit at the control levers of the future. Their decisions, aggregated over time, determine what gets built and what is left to decay, which problems are solved and which are allowed to fester. This power comes with a moral obligation that transcends the simple duty to maximize financial returns. It is an obligation to act as true fiduciaries for the future, to manage the wealth of the present in a way that creates a richer, more durable, and more just world for generations to come.

The Doctrine of Positive Utility is our answer to this obligation. It is a framework for thought and a guide for action. It is presented here not as a final, perfect word, but as the beginning of a crucial conversation. We offer it as an open invitation to investors, to economists, to policymakers, and to citizens to join us in the work of building this future—to adopt these principles, to critique them, to improve upon them, and to help us forge a new consensus around an economics of human flourishing.

The Logic of Surplus—And the Next Reckoning

This doctrine began with a simple proposition: that the problem with American capitalism is not that it is too ambitious but that it aims too low. It measures value in narrow units of quarterly profit, ignoring the larger ledger of costs and benefits that determine whether a society grows or decays. If we measure only what accrues to shareholders—and ignore what is extracted from everyone else—we end up with a system that harvests capital today by consuming the capability of tomorrow. The Doctrine of Positive Utility is offered as a corrective: an argument that our highest ambition must be the compounding of human flourishing itself, and that any accounting framework blind to this reality is both morally negligent and mathematically unsound.

Yet if we are honest, we must admit that the same critique applies beyond the private sector. The institutions of government—tasked with the stewardship of public resources—are no less susceptible to the same time-horizon myopia and the same conceptual failures. What is deficit spending to fund an endless, extractive war if not the fiscal equivalent of a payday lender’s balance sheet: superficially solvent in the present, functionally bankrupt in the future? What is a government that invests trillions in oil conquest but balks at the cost of universal literacy if not an institution that has lost the thread of value itself?

So while this paper has focused on the practice of investing, it must be clear that this is only the beginning. The redefinition of value does not end at the edge of the market. It demands a parallel redefinition of what it means to be fiscally conservative: not the reflexive hoarding of resources, nor the convenient austerity that spares the powerful while starving the public good, but the disciplined insistence that every dollar deployed must yield a durable, positive return on the capability of the American people.

To be truly fiscally conservative is not to spend nothing. It is to refuse to spend on anything that destroys the compounding asset base of our civilization—whether it is a subsidized carcinogen, a socially corrosive algorithm, or a misbegotten war. And it is to be willing to spend boldly, even lavishly, when the investment generates the only surplus that ultimately matters: healthier citizens, more capable minds, and a society resilient enough to survive the crises no balance sheet can yet predict.

And if all else fails, perhaps we will borrow a final lesson from Warren Buffett—albeit with a more unflinching edge. Let us propose, tongue only partly in cheek, that whenever the national deficit exceeds three percent of GDP, every seat of power be vacated. No exceptions. Not the Congress, not the Cabinet, not the Supreme Court, not the executive branch. A full tabula rasa, cleansing the institution of its accumulated complacency and reminding every would-be steward that real value—like real legitimacy—is earned, not inherited.

Because in the end, whether we are allocating a pension fund or administering a republic, the first principle remains the same: when we define value narrowly, we end up extracting from the very future we claim to protect. When we define it wisely, we build something that outlasts us all.

“Someone’s sitting in the shade today because someone planted a tree a long time ago.”

- Warren Buffet

Appendices

A. Glossary of Terms

Capability Approach: A theoretical framework, pioneered by Amartya Sen, that assesses well-being, development, and social justice in terms of people's effective opportunities ("capabilities") to achieve the states and actions ("functionings") they have reason to value. It shifts the focus from resources (like income) to real freedoms.18

Compounding Capability: A core principle of the Doctrine of Positive Utility. It posits that human capability (e.g., health, education), unlike physical capital, compounds over time. Investments in human capability create a virtuous cycle of increasing productivity, innovation, and well-being.

Doctrine of Positive Utility: The comprehensive philosophical and investment framework detailed in this paper. Its central tenet is that true value is the creation of net societal surplus, measured by the expansion of human capability and flourishing.

Economic Moat: A term popularized by Warren Buffett to describe a business's sustainable competitive advantage that protects its long-term profits from competitors. Examples include strong brands, low-cost production, or network effects.49

Functionings: In the Capability Approach, functionings are the various "beings and doings" that a person achieves. Examples include being well-nourished, being educated, or having self-respect.22

Negative Externality: A cost imposed on a third party as an indirect effect of an economic transaction. The party causing the harm does not compensate the party that is harmed. For example, air pollution from a factory that harms the health of local residents.2

Net Surplus Creation: A principle of the doctrine defining true value as the total positive value an entity creates for all stakeholders (customers, employees, society, environment) minus the total costs it imposes, both financial and external.

Positive Utility: Any measurable impact of an enterprise's activities that verifiably increases human capability, health, dignity, and resilience. The opposite of Negative Utility.

Positive Utility Scorecard: The primary analytical tool of the doctrine. A multi-factor scoring system, based on Martha Nussbaum's ten central capabilities, used to assess an investment's net contribution to societal well-being in a non-monetized way.

Time-Horizon Myopia: A cognitive and institutional bias toward short-term results that leads to the systematic undervaluing of long-term consequences and risks. It is often exacerbated by market structures like quarterly reporting.1

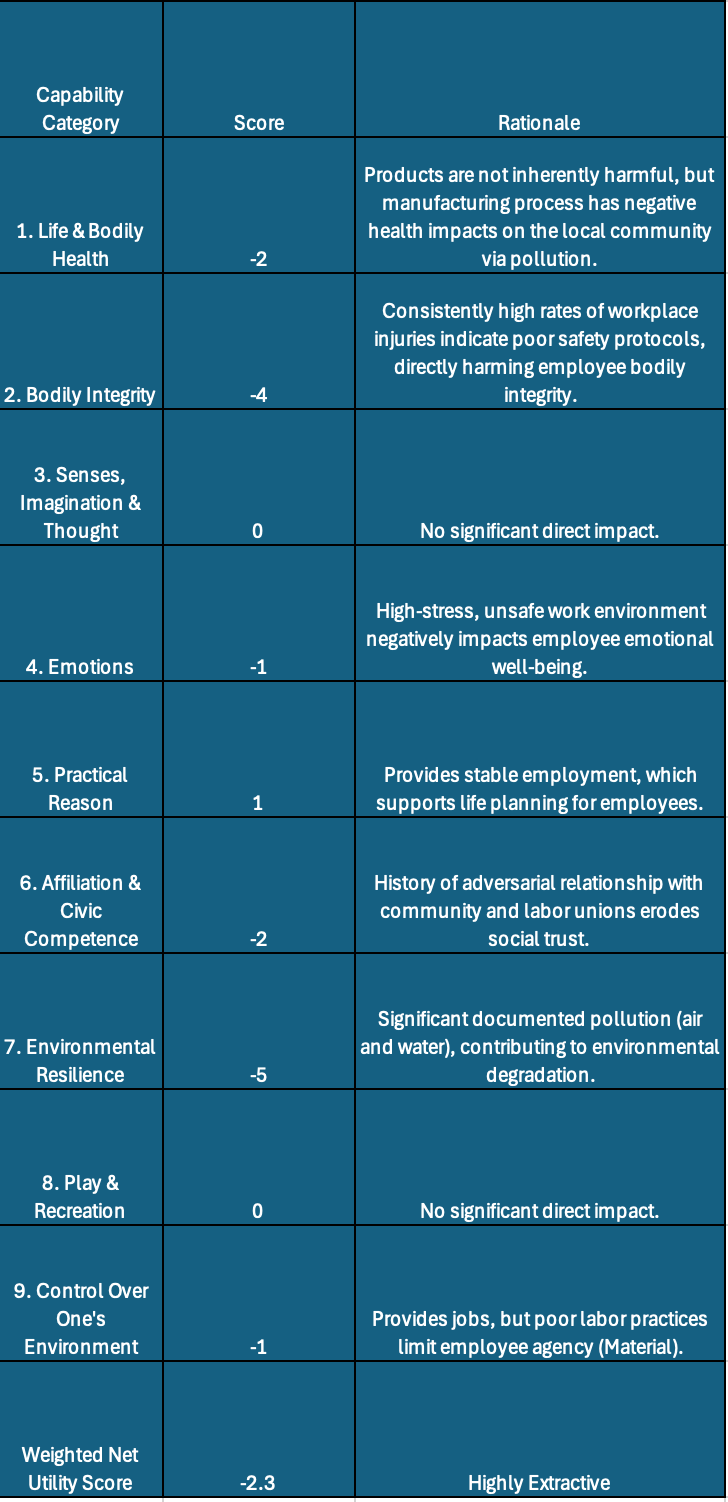

B. Sample Positive Utility Scorecards

The following are simplified, illustrative examples of how the Positive Utility Scorecard might be applied. In practice, each score would be supported by a detailed memorandum with quantitative and qualitative evidence. The scale runs from -5 (profoundly negative impact) to +5 (profoundly positive impact).

Example 1: "HealthGuard" - A Preventive Healthtech Company

Business Model: Provides an AI-driven mobile application that uses wearable data to predict and prevent the onset of chronic diseases like type 2 diabetes and hypertension, offering personalized lifestyle interventions.

Example 2: "Legacy Manufacturing Inc." - A Traditional Industrial Company

Business Model: Manufactures industrial components. Profitable, but with a history of environmental fines and a high worker injury rate.

C. Full Case Study: Duolingo vs. DraftKings

This case study demonstrates the application of the Positive Utility Framework to two well-known public companies with vastly different societal impacts.

Duolingo Inc.

Financial Profile & Business Model: Duolingo is a language-learning platform operating on a "freemium" model. A substantial portion of its content is available for free, supported by advertising. Users can upgrade to a premium subscription ("Super Duolingo") to remove ads and access additional features. The company has demonstrated strong revenue growth driven by a growing subscriber base. Its mission is "to develop the best education in the world and make it universally available".32

Positive Utility Analysis:

Senses, Imagination & Thought (+5): Duolingo's core product directly and massively contributes to this capability. By making language education accessible to hundreds of millions of users globally, it enhances cognitive abilities, opens up new cultural experiences, and improves educational and employment opportunities. The free accessibility is a critical factor, generating an enormous positive externality in human capital formation.

Control Over One's Environment (Material) (+3): Language proficiency is a key factor in economic mobility. By providing a free and effective tool for learning a new language, Duolingo gives individuals a tangible asset they can use to seek better employment, participate in the global economy, and improve their material circumstances.

Affiliation & Civic Competence (+2): Language is the foundation of communication and cultural understanding. By breaking down language barriers, Duolingo facilitates cross-cultural connection and empathy, contributing positively to social affiliation.

Other Capabilities: The impact on other capabilities is less direct but generally neutral to slightly positive.

Conclusion: Duolingo is a prime example of a highly generative enterprise. Its business model is intrinsically aligned with the creation of positive utility. While it is a for-profit company that generates revenue, its primary output is a massive net surplus of human capability in the form of education. It scores exceptionally high on the Positive Utility Scorecard and would be a priority investment for the American Endowment.

DraftKings Inc.

Financial Profile & Business Model: DraftKings is a digital sports entertainment and gaming company. Its primary revenue streams are online sports betting (OSB) and iGaming (online casino games). The company takes a percentage of the total amount wagered (the "handle") as revenue. The business model relies on acquiring and retaining users who participate in these paid gambling activities.65

Positive Utility Analysis:

Control Over One's Environment (Material) (-5): The core business model is predicated on an activity—gambling—that is strongly associated with addiction and financial distress. For a significant subset of users, the product leads directly to a loss of control over their financial resources, pushing them into debt and poverty. This is a profound negative impact on this capability.

Emotions (-4): Gambling addiction is a recognized behavioral disorder that causes significant emotional and psychological harm, including anxiety, depression, and stress on family relationships. The business model profits from and encourages behavior that is damaging to the emotional well-being of its most engaged users.

Practical Reason (-3): The nature of gambling addiction undermines an individual's capacity for rational financial planning. The business model is antithetical to the development of prudent, long-term decision-making.

Play & Recreation (?): Proponents might argue that DraftKings provides a form of entertainment and recreation. However, the "Play" capability on Nussbaum's list refers to activities that are joyful and restorative. When "play" becomes a vector for financial loss and addiction, it ceases to have positive utility and becomes a source of harm. The potential for negative outcomes far outweighs any recreational benefit.