Optimism Leveraged vs. Obligation Collateralized: How U.S. and Chinese Debt Aren’t the Same Thing

What is debt, except an obligation of duty to those around us? Your primer on debt, what it means, and why it matters beyond the realm of finance.

“If history shows anything, it is that there's no better way to justify relations founded on violence, to make such relations seem moral, than by reframing them in the language of debt—above all, because it immediately makes it seem that it's the victim who's doing something wrong.” — David Graeber, Debt: The First 5,000 Years 1

“To analyze Chinese debt with an American lexicon… is to read a Confucian classic and see only a flawed prospectus.”

The West’s Favorite Bedtime Story

There exists a peculiar and highly profitable cottage industry in the West, a digital ghost story told around the warm glow of a million screens. It is a tale of imminent, spectacular collapse. The protagonist of this story is always the same: the People’s Republic of China. One need only wade into the shallowest currents of YouTube to find it. A financial news channel, Casgains Academy, announces with breathless certainty, “China's Economy Will Collapse In 34 Days,” a proclamation that nets 3.2 million views. The finance personality Andrei Jikh tells his 2.2 million subscribers the end will come in “a matter of days.” Graham Stephan, a real estate investor with more followers than The Wall Street Journal, declares, “It's Over: China's ENTIRE Economy Is About To Collapse”.4 Geopolitical strategist Peter Zeihan has built a formidable brand on the thesis that “there won't be a China” by roughly 2034, citing a system consumed by "rot".5 This content genre, a form of what can only be described as “collapse porn,” is not a fringe phenomenon. It is a mainstream, bipartisan, and voraciously consumed narrative, a constant drumbeat of impending doom that has echoed for decades, promising a reckoning that never quite arrives.4

This digital cacophony exists in a state of profound cognitive dissonance with the quiet, methodical reality on the ground in China. While Western pundits predict a financial apocalypse born of debt, the Chinese household remains one of a saver, not a debtor. In 2024, China's per capita saving rate stood at a remarkable 24.5%, a figure that, while down from its pandemic peak, remains significantly above pre-pandemic norms, signaling that a culture of caution has become the new baseline.8 This is not an abstract statistic. It is the lived reality of families who have saved for years, scrimping and saving to pay for a child’s overseas education upfront, in cash, viewing it not as a leveraged investment in an individual’s future but as the fulfillment of a generational obligation.10 It is the reality of a government that, in the face of a world-historic property crisis, prioritizes the delivery of pre-paid apartments to domestic citizens over the sanctity of contracts with foreign bondholders.12 While the West watches for a Lehman Brothers moment, China is meticulously managing an internal family dispute, ensuring the children are cared for before the creditors are paid.

The stark contrast between the Western narrative and the Chinese reality reveals a deeper truth, one best captured by a simple axiom: People who are winning don’t need to announce victory every day. The relentless Western insistence on China’s imminent collapse is not the product of objective analysis. It is a symptom of profound anxiety, a psychological projection born from a fundamental, category-level misreading of what “debt” means in the two civilizations. American debt is an instrument of self-amplification—an optimism bet that tomorrow’s growth will bail out today’s consumption—while Chinese debt functions as a relational obligation embedded in family, state, and social hierarchy. This is not a mere semantic distinction; it is a chasm in civilizational logic. Misreading that difference fuels the West’s “China is collapsing” cope narrative and, more dangerously, blinds Americans to the reality of their own creeping moral and institutional insolvency. To understand the debt of one is to understand its dreams; to understand the debt of the other is to understand its duties. The failure to distinguish between the two is the single greatest analytical error of our time.

Narrative Triage: The ‘China Collapse’ as Imperial Self-Soothing

The persistent, almost ritualistic, prediction of China's downfall serves a purpose that has little to do with economic forecasting and everything to do with psychological self-preservation. The genre is best understood not as analysis but as a collective therapy session for a declining hegemon. It is a textbook case of projection: the act of externalizing one’s own unacknowledged anxieties and institutional decay onto a rival. The more precarious America’s own footing becomes, the more desperately its commentariat needs to believe that its primary competitor is on the verge of self-destruction. This is not a new phenomenon. Gordon G. Chang’s 2001 book, The Coming Collapse of China, famously predicted the end of the People's Republic by 2011. When that date passed, he simply revised the forecast to 2012, and has continued to do so since, becoming a recurring punchline among serious analysts but remaining a fixture in the doom-narrative circuit.13 The narrative’s immunity to falsification is the surest sign that its function is psychological, not analytical. As one Chinese observer noted, "the West has been predicting the demise... for for decades. And they never quite got it right".15 The question is not why they are wrong, but why they need to be.

The answer lies in America’s own fraying social and economic fabric. The act of projecting unsustainability onto China allows the United States to avoid a painful confrontation with its own balance sheet—a ledger that shows deep and growing deficits not just in dollars, but in social cohesion, physical well-being, and civic trust. A brief, dispassionate audit of the American condition reveals the source of this ambient anxiety.

First, the social fabric is tearing. U.S. life expectancy, a bedrock indicator of national well-being, has stagnated and fallen relative to its peer countries. Between 2019 and 2022, the U.S. experienced a sharper decline and a slower rebound than comparable nations, and by 2023, American life expectancy of 78.4 years was still 4.1 years shorter than the peer average.16 This is not merely a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic but the culmination of a longer-term trend driven by what economists have termed "deaths of despair," including rising mortality from suicides and overdoses, alongside a growing burden of chronic disease.16 In 2022, a U.S. male could expect to live to 74.8, while a female could expect to live to 80.2, both figures lower than in any other large, wealthy country.17

Second, the nation's financial health is deteriorating. The American household, the supposed engine of global consumption, is saving at a dangerously low rate. As of 2024, the personal saving rate stood at just 3.8%, well below its 20-year average of 5.9%.19 This culture of consumption is mirrored at the federal level, where fiscal discipline has all but vanished. Fiscal year 2024 marked the fifth consecutive year with a budget deficit exceeding $1 trillion, closing at a staggering $1.8 trillion, or 6.4% of GDP.21 This is nearly double the pre-pandemic deficit of 2019 and higher in nominal dollars than at any point in history outside the acute crises of 2020 and 2021.24 The national debt now stands at 123% of GDP, with projections showing it will reach its historical high of 106% of the economy by 2027.22

Third, and perhaps most critically, the civic trust that underpins the entire system is in a state of collapse. Confidence in nearly every major American institution has cratered to historic lows. A 2024 Gallup poll paints a devastating picture: only 7% of Americans have a "great deal" or "quite a lot" of confidence in Congress. The presidency commands the confidence of just 23%, and the Supreme Court, once a bastion of institutional legitimacy, has fallen to 25%.26 The decline extends beyond government. Confidence in newspapers is at 16%, the criminal justice system at 14%, and big business at 14%.26 The average confidence across 16 major institutions has hit a new low of 27%.26 Other surveys confirm this trend, showing a steady erosion of trust over five decades, regardless of which party holds power, creating a crisis of legitimacy that threatens the very health of the democracy.27

This is the context in which the "China collapse" narrative must be understood. It is not economic analysis; it is narrative triage. It is an emergency psychological intervention for a fraying empire, a coping mechanism that allows a nation grappling with declining life expectancy, crumbling finances, and vanishing social trust to point its finger outward and declare that the real problem, the real unsustainability, lies elsewhere. The popularity of this content is not a leading indicator of China’s future but a lagging indicator of America’s present anxiety. The louder the predictions of a crash in Beijing, the more we can infer about the depth of the unacknowledged crisis in Washington.

The Semantics of Solvency: A Tale of Two Debts

The fundamental error in Western analysis of Chinese debt is linguistic. Analysts deploy the word "debt" as if it were a universal constant, a fungible term with a fixed meaning governed by the iron laws of economics. It is not. The word "debt" is a homonym in the American and Chinese contexts; it sounds the same, but it refers to two entirely different social, moral, and political technologies. In the United States, debt is an instrument of individual leverage. In China, it is an instrument of relational obligation. This semantic split, rooted in the foundational cultural DNA of each civilization, explains everything from household savings rates to the state’s response to a financial crisis.

The American Definition: Debt as a Hero’s Leverage

The American cultural mythos, particularly in its modern, neoliberal form, is built upon the altar of the sovereign individual. The famous assertion by Margaret Thatcher that "there is no such thing as society. There are individual men and women and there are families" is not an outlier but the distilled essence of an entire worldview.2 This ethos, echoed in Ronald Reagan's championing of "individual freedom and the dignity of all people," reframes the concept of debt.30 It is not a moral failing or a social burden, but a tool, a "growth hack" for personal advancement. Debt is the leverage the lone protagonist uses to propel their hero's journey.

This cultural script is written into the very structure of American life. A student loan is a rational investment in one’s own human capital, a 20-year repayment plan for a brighter future.31 A credit card is a tool to smooth consumption and acquire the signifiers of success. A mortgage is the primary vehicle for asset accumulation. Venture capital is the fuel for a founder’s vision, a bet made with "other people's money" on a disruptive future. This mindset is psychologically ingrained. American culture operates on a principle of "temporal discounting," a cognitive bias that prioritizes immediate gratification over long-term security, a tendency that credit systems masterfully exploit.33 This is not seen as a weakness but as a feature: a bias toward action, optimism, and risk. Cross-cultural studies of corporate finance confirm this, finding that cultures high in individualism, like the United States, are associated with higher risk-taking and a greater appetite for leverage.34 The American balance sheet, from the household to the federal government, is the product of this worldview: a testament to the belief that one can, and should, borrow from tomorrow to pay for today.33

The Chinese Definition: Debt as a Binding Obligation

In the Chinese civilizational context, the individual is not a discrete atom but a node within a dense network of relationships.36 The foundational moral operating system is Confucianism, which prioritizes social harmony, collective interest, and righteousness (yi, 義) over the pursuit of individual profit.37 Within this moral economy, debt is not a financial instrument but a social adhesive that binds people together through a web of duties.

The primordial debt is that of filial piety (孝, xiào). This is the core principle of the Confucian worldview, where the parent-child relationship serves as the model for all other social relations.40 Parents give the gift of life, nurture, and education. In return, the child incurs a debt that can never be fully repaid.40 This is not a transactional liability to be discharged but a lifelong moral duty that structures one's identity and behavior. It demands obedience, respect, and material support for one's parents, an obligation that supersedes all others.40 This concept of unpayable, inherited obligation is the psychological bedrock upon which the entire Chinese understanding of debt is built.

This logic extends from the family outward into the social and commercial spheres through the concept of guanxi (关系). Often mistranslated as mere "networking," guanxi is a far deeper system of mutual, long-term obligations built on trust and the continuous exchange of favors.45 It is a social ledger where every Chinese individual maintains a mental abacus of favors given and "social debts" owed.47 To incur a debt within a guanxi network is to place a strain on a critical relationship, a strain that must be managed to preserve social harmony and, crucially, "face" (mianzi, 面子). A default is therefore not primarily a financial event; it is a profound social and moral failure, a violation of trust that can sever one's ties to the community. For all concerned, expectations are clear: the relationship is the collateral.

This fundamental difference in the conception of debt leads to a crucial divergence in its function. In the United States, debt is a tool to escape constraints. A student loan allows a young person to leave their hometown and transcend their family's social station. A business loan allows an entrepreneur to break free from the constraints of their 9-to-5 job. Debt is an instrument of liberation, a way for the individual protagonist to rewrite their own story. In China, debt is a tool to reinforce constraints. The primordial debt of filial piety binds the individual to the family hierarchy. The social debts of guanxi bind the individual to their community network. The financial debts owed to state banks bind individuals and enterprises to the priorities of the state. Debt does not liberate; it obligates. It deepens one's embeddedness within the existing structure. This distinction explains why the state response to crises is so different. When the American system faced collapse in 2008, the government intervened to save the abstract system—the market itself. When the Chinese system faces a crisis like Evergrande, the government intervenes to preserve the concrete structure—the hierarchy of social obligations, ensuring homebuyers are housed and suppliers are paid before abstract financial instruments are honored. To analyze one with the logic of the other is to commit a category error of civilizational proportions.

The Fortress Balance Sheet of a Civilization (thx Jamie)

These divergent cultural philosophies of debt have not remained in the realm of abstraction; they have been institutionalized, creating two fundamentally different national balance sheets and two distinct models of economic stability and vulnerability. One operates as an open loop, dependent on external confidence and perpetual growth. The other operates as a closed loop, dependent on internal control and social cohesion.

America's Open Loop: The Optimism Bubble

The American financial system is built on a structural deficit of domestic savings. With a personal savings rate hovering below 4%, the nation consumes more than it produces and invests more than it saves.19 This gap, by accounting identity, must be filled by borrowing from abroad.48 This dynamic has transformed the U.S. Treasury market into the world's de facto savings account, the ultimate safe asset for foreign governments, corporations, and private investors. As of 2024, foreign entities hold between $7.9 trillion and $8.5 trillion in U.S. government debt, accounting for approximately 23% to 30% of the total debt held by the public.48 The largest foreign creditors include Japan (approximately $1.1 trillion), the United Kingdom ($808 billion), and, despite recent reductions, China ($757 billion).48

This arrangement is often lauded as America's "exorbitant privilege," allowing it to fund its deficits and consumption in its own currency. However, it is also a profound structural vulnerability. The stability of the U.S. economy is inextricably linked to the continued willingness of foreign actors to finance its profligacy. This reliance creates a subtle but significant loss of sovereignty, where domestic policy decisions, particularly the Federal Reserve's interest rate policies, are perpetually constrained by the need to maintain the attractiveness of U.S. assets to foreign capital. While the share of foreign ownership has declined from its peak of 33.9% in 2014 49, the absolute dependence on this inflow of capital remains a cornerstone of the American economic model. It is a system that runs on optimism, collateralized by the faith of external creditors.

China's Closed Loop: The Fortress Economy

In stark contrast, China's financial architecture is fundamentally insular and state-directed. It functions as a closed, internally funded loop, designed for control and resilience rather than global integration.

The engine of this system is an extraordinarily high domestic savings rate. Driven by a combination of cultural predisposition, a still-developing social safety net, and demographic pressures, Chinese households save a massive portion of their income, creating a vast domestic capital pool.8 In 2023, the household savings rate was 31.7%, with cash and deposits amounting to RMB 149 trillion.54

This immense pool of savings is then channeled through a state-controlled conduit: the large, state-owned banks (SOBs). These banks do not operate primarily on market principles; they function as arms of the state, executing national policy.55

The final destination for this capital is a network of state-prioritized entities, primarily state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and local government financing vehicles (LGFVs). These entities are tasked with carrying out the state's developmental agenda, which has historically focused on massive investments in infrastructure, real estate, and strategic industries.56

This closed-loop system is notoriously inefficient. It encourages malinvestment, creates enormous waste, and has fueled the very property and debt bubbles that Western analysts now point to as evidence of imminent collapse.58 However, to focus solely on its inefficiency is to miss its primary strategic virtue: control. Within this system, a debt crisis is not a market event to be managed by price signals and panicked investors. It is an internal, political problem to be resolved within the "family" of the state. The debt is owed by one state-affiliated entity (an LGFV) to another (a state bank), often collateralized by state-owned land, and ultimately backstopped by the immense savings of the Chinese people. The system is designed to absorb shocks and manage crises through administrative fiat rather than market-driven contagion. It is a fortress economy, inefficient and cumbersome, but built to withstand external storms.

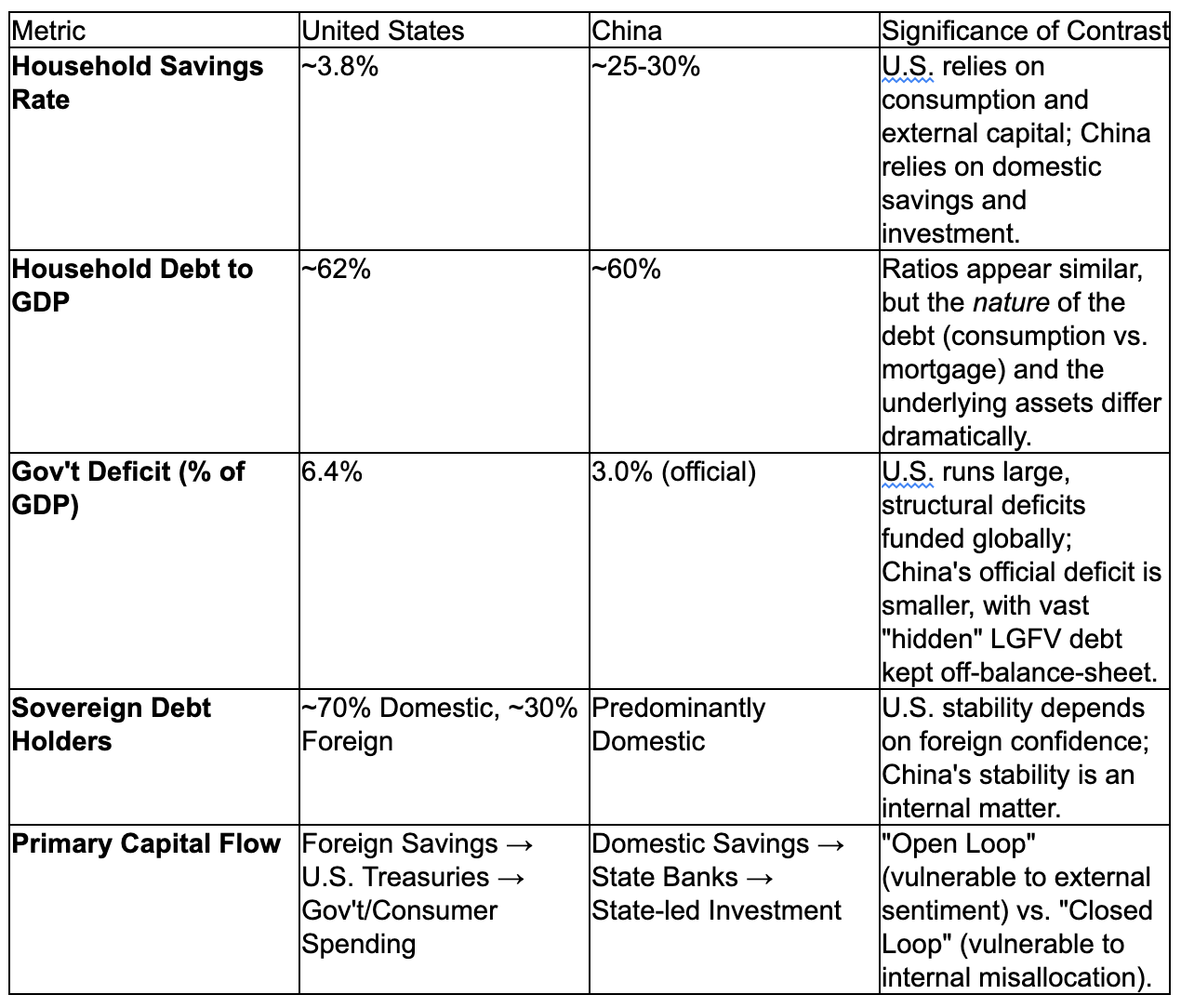

The table below starkly illustrates the structural differences between these two civilizational balance sheets.

Table 1: A Tale of Two Ledgers: Comparative Financial Architectures (2024 Data)

The data in this table provides the empirical backbone for the "Open Loop vs. Closed Loop" framework. While a metric like Household Debt-to-GDP may appear superficially similar in both countries, the underlying reality is profoundly different. U.S. household debt is heavily weighted towards credit cards and other forms of consumption, while Chinese household debt is overwhelmingly dominated by mortgages, often for properties that have been fully paid for by extended family savings.67 Similarly, the contrast in sovereign debt holders is not just a number; it is a fundamental statement about sovereignty and systemic risk. The U.S. system is a globalized network of interdependencies, while the Chinese system is a nationalized hierarchy of control. These are not merely different economic models; they are different civilizational strategies for managing risk, time, and obligation.

Five Case Studies in Contrast

The theoretical and structural differences between the American and Chinese conceptions of debt manifest in starkly divergent real-world outcomes. By examining five parallel domains—education funding, municipal finance, property crises, pandemic stimulus, and social trust—we can see these abstract civilizational logics in concrete action. Each case study serves as a miniature chapter, illustrating how the same challenge elicits fundamentally different responses, revealing the deep cultural programming that underwrites each nation's balance sheet.

1. The Cost of a Future: U.S. Student Loans vs. "Tiger Parent" Cash Tuition

In the United States, higher education is framed as a personal investment, a transaction for upward mobility that is commodified into a financial product: the student loan. The system is designed around the individual as the primary economic agent. Federal programs like Direct Stafford Loans and PLUS Loans, alongside a robust private lending market, enable individuals to borrow against their future earnings to fund their education.32 This creates a decades-long debt obligation, managed through a complex ecosystem of loan servicers and structured repayment plans that can extend from 10 to 30 years.31 The debt is an individual's entry ticket to the middle class, a personal liability assumed in the pursuit of a personal dream. The total student loan debt in the U.S. now exceeds $1.75 trillion, a testament to the scale of this individualized, credit-based model.33

In China, the logic is inverted. Education is not an individual investment but a paramount family obligation, a sacred duty rooted in Confucian values and the all-encompassing principle of filial piety.44 It is the parents' non-negotiable responsibility to provide for their child's education, and the child's reciprocal duty to succeed. This moral framework produces a completely different financial reality. Chinese families, even those with modest incomes, save for years, often liquidating major assets, to pay for tuition and fees upfront, in cash.10 More than 80 percent of Chinese undergraduates studying in the U.S. pay their costs from personal or family sources.10 The financial burden is immense, consuming an average of 17.1% of total household income and, for the lowest income quartile, a staggering 56.8%.70 Yet, this is not treated as a financial liability to be amortized over time. It is a moral debt to the next generation, a collective sacrifice discharged before the education even begins.

The obligation is intergenerational and familial, not financial and individual. The contrast is absolute: one system creates a financial asset for lenders and a long-term liability for the individual student; the other mobilizes the entire family's savings to fulfill a social duty, leaving the student financially unburdened but morally indebted to their lineage.

2. When the City Goes Broke: The Public Bankruptcy of Detroit vs. The Opaque Restructuring of LGFVs

When a U.S. municipality faces insolvency, it enters a transparent, adversarial, and legalistic process: Chapter 9 bankruptcy. The 2013 case of Detroit, which filed for bankruptcy with over $18 billion in debt, is the archetypal example.72 The process was public and governed by federal law. It involved court filings accessible to the public, formal negotiations between the city and its various classes of creditors (including bondholders and pension funds), and a court-approved "plan of adjustment" that publicly and legally imposed losses on stakeholders.73 The failure and its resolution were a public spectacle, adjudicated in the open according to established rules. It was a market-based process for resolving the failure of a public entity.

China's approach to municipal distress could not be more different. Since the 1994 fiscal reforms, local governments have been officially prohibited from borrowing directly and are required to maintain balanced budgets.75 To circumvent this, they created tens of thousands of off-balance-sheet entities known as Local Government Financing Vehicles (LGFVs). These quasi-corporate bodies borrow from state banks and bond markets to fund infrastructure projects, accumulating a mountain of "hidden debt" estimated to be between $7 trillion and $11 trillion.75 When these LGFVs face financial distress, there is no public bankruptcy. Instead, the state orchestrates an opaque, internal restructuring. The process is a family affair, managed behind closed doors to preserve stability and "face." Local governments convene meetings between the LGFVs and their primary creditors (almost always state-owned banks) and instruct them to find a solution.77 Debts are rolled over, maturities are extended by years or even decades, interest rates are lowered, and state banks are quietly directed to provide forbearance.60 The central government may issue "refinancing bonds" to swap high-cost debt for lower-cost, state-backed bonds.60 The problem is not resolved in a legal sense; it is managed in a political one. The debt is perpetually "kicked down the road," but within a closed system that possesses a very, very long road.

3. Property Bubbles: The Global Contagion of 2008 vs. The Contained Implosion of Evergrande

The 2008 global financial crisis, originating in the U.S. subprime mortgage market, was a catastrophic failure of a market-based, globalized financial system. The crisis spread like a virus through a complex web of mortgage-backed securities and credit default swaps held by financial institutions around the world. The U.S. government's response, epitomized by the $700 billion Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), was a massive public bailout designed to prevent the collapse of the entire global financial system.79 The priority was to save the systemically important financial institutions—the banks, investment houses, and insurance companies like Citigroup, Bank of America, and AIG—to prevent a cascade of failures that would freeze global credit markets.79 The losses were effectively socialized to protect the integrity of the global market, with direct relief for homeowners being a secondary and far less effective component of the response.82

The crisis surrounding China Evergrande Group, which defaulted on over $300 billion in liabilities, is a failure within a state-controlled system, and the response reflects a completely different set of priorities.83 Beijing's approach has been pointedly not to bail out the company or its creditors in a Western sense. Instead, the government has stepped in as an executor, not a savior, to manage the demolition and allocate the pain according to a clear political hierarchy. The absolute top priority is social stability: ensuring that millions of ordinary Chinese citizens who pre-paid for apartments receive their finished homes ("保交楼," bǎo jiāo lóu—protect the delivery of buildings).

The second priority is to ensure that domestic suppliers, contractors, and construction workers are paid. The third is to recapitalize the domestic state-owned banks that are exposed. A distant last on this list are the foreign bondholders, who have been largely left to absorb their losses through a liquidation process in Hong Kong that has little jurisdiction over Evergrande's mainland assets.12 The state is not saving the market; it is reallocating assets to preserve the social order. The pain is being carefully contained and distributed within the national system, reinforcing the principle that domestic social obligations trump foreign financial contracts.

4. Pandemic Response: American Consumption Checks vs. Chinese Production Credits

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Asymmetric Risk— Andrew's Almanac to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.