Bush Did 9/11, But Because His Daddy Told Him To

How Oil, Empire, and Ego Built the Dollar, Broke the World, and Paved the Way for a New Commodity Order

A Legacy of Oil, Empire, and a Fateful September

On September 11, 2001, the world witnessed a cataclysmic event that reshaped geopolitics. In the aftermath, many asked “Why?” The official answers pointed to terrorism and ideology, but a deeper look suggests a convergence of oil, empire, and ego-driven agendas decades in the making. The provocative notion that “Bush did 9/11” (that the Bush administration may have facilitated or exploited the attacks) speaks to a broader thesis: the attacks provided a “Pearl Harbor” moment long sought by American power brokers to extend U.S. dominance – especially over oil-rich regions. And “because his daddy told him to” hints at the dynastic continuity of the Bush family’s imperial ambitions, rooted in oil and the CIA. This essay investigates how the petrodollar system – born from 1970s crises and savvy deals – built the U.S. dollar’s supremacy, how maintaining that system drove American wars (from Iraq to Libya), and how the wreckage of this era is now giving rise to a new, digital and multipolar commodity order. We’ll explore declassified documents, historical data, and case studies to connect the dots between Bretton Woods’ collapse, the Bush family’s shadowy history, the Project for a New American Century’s vision, and the emerging challengers to dollar hegemony. The goal is a bold, well-researched look at how oil and empire intertwined to “break the world” – and what might come next.

From Bretton Woods to Petrodollars: How Oil Rescued the Dollar

In the aftermath of World War II, the United States crafted the Bretton Woods system, anchoring the global economy to the U.S. dollar, which was in turn pegged to gold at $35/oz. This arrangement cemented the dollar as “good as gold” and the world’s reserve currency . By the late 1960s, however, America’s guns-and-butter spending – financing the Vietnam War and expansive domestic programs – strained this order . Countries lost trust in the dollar’s stability and began redeeming dollars for U.S. gold. In 1971, President Nixon ended dollar-gold convertibility, effectively collapsing Bretton Woods . The world was thrust onto a pure fiat dollar standard, and U.S. policymakers faced a dire question: Without gold backing, what would sustain global demand for the dollar?

They found an answer in black gold – oil. In October 1973, amid the Yom Kippur War, Arab OPEC nations launched an oil embargo against the U.S., sending oil prices skyrocketing and exposing the West’s vulnerability . As oil quintupled in price, a windfall flowed to Saudi Arabia and other exporters. The Nixon (and then Ford) administration saw an opportunity: partner with Saudi Arabia, the de facto leader of OPEC, to denominate oil exclusively in U.S. dollars. In 1974, U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger struck a secret pact with Riyadh: Saudi Arabia would price all its oil exports in USD and invest its oil revenues back into U.S. Treasury bonds and American assets; in return, the U.S. would provide military protection and arms to the Saudi regime . This arrangement – the birth of the “petrodollar” – meant any country seeking to buy oil on world markets now had to hold U.S. dollars, propping up the dollar’s value. It also created a massive petrodollar recycling loop: oil riches from Riyadh and OPEC flowed into Wall Street and Washington, financing U.S. deficits and military might .

Other OPEC members gradually followed Saudi Arabia’s lead, solidifying a 1970s oil-for-dollars order. By the end of the decade, most global oil trade was conducted in dollars, and American power was effectively backed not by gold, but by oil. As one analysis describes, “oil exports from Saudi Arabia (and later OPEC broadly) have been priced in U.S. dollars since 1974, ensuring a constant global demand for the dollar and U.S. Treasury assets.” This petrodollar system quietly underwrote U.S. economic dominance for the next 50 years. It allowed the U.S. to run huge trade deficits (importing goods and oil in exchange for paper dollars) without jeopardizing its currency – the excess dollars were absorbed by foreign central banks and investment funds purchasing U.S. bonds. It also funded the U.S. military-industrial complex: oil-rich allies bought American weapons (recycling dollars back) while the U.S. built a military force capable of intervening in any oil-producing region to defend the petrodollar deal.

Critically, this arrangement “ruined the world” in ways that went unnoticed for years. It tied the health of the global economy to an insatiable thirst for petroleum (with dire ecological consequences), and it entrenched U.S. hegemony, breeding resentment. Poorer nations bore the brunt: they needed dollars to buy oil, forcing them to earn or borrow USD at whatever cost . Meanwhile, Washington could sanction adversaries by denying them access to dollars – a potent geopolitical weapon. The petrodollar was like a hidden tax or tribute system funneling wealth and power to the U.S. center. But maintaining it would come at a high price, often paid in blood.

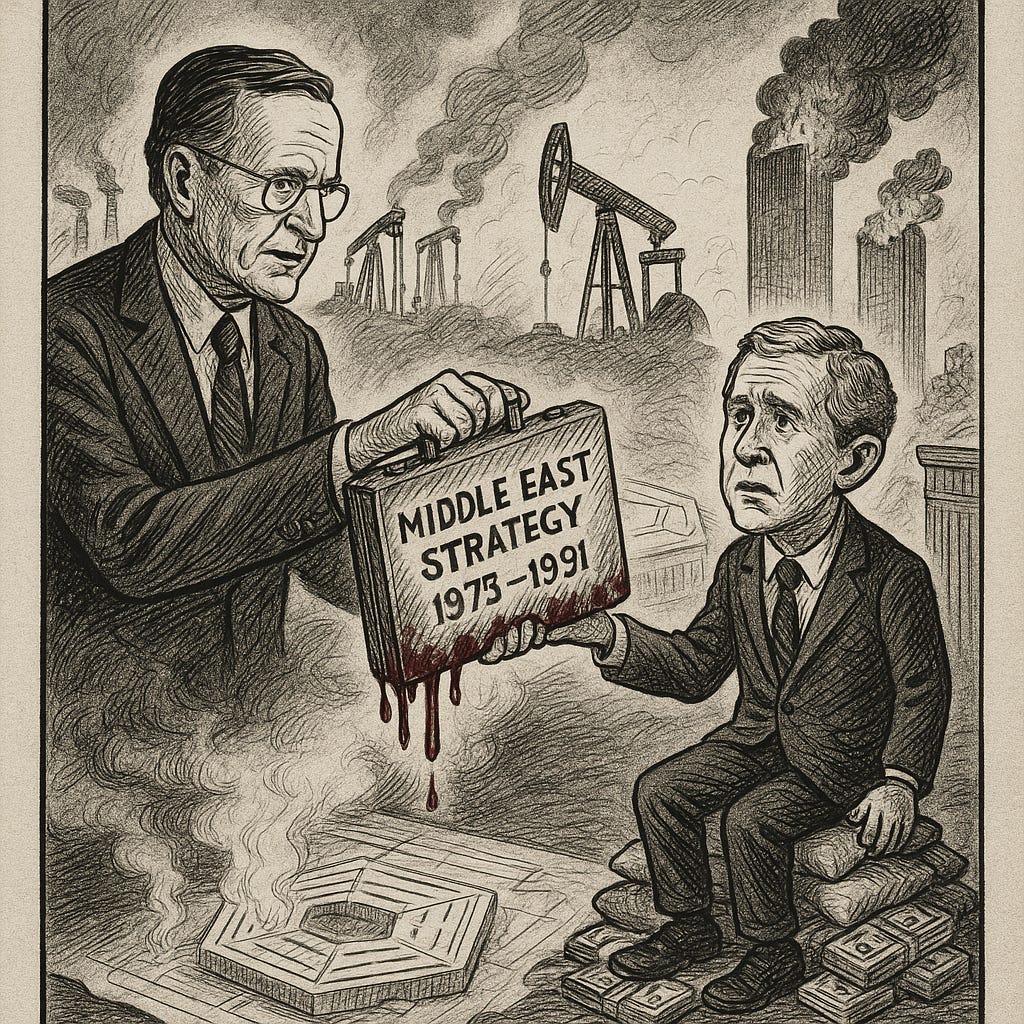

Bush’s Stealth Empire: Oil, the CIA, and Family Secrets

Long before George W. Bush presided over the War on Terror, his father and grandfather helped forge the marriage of American oil and covert power. The Bush family story reads like a case study in the military-oil-industrial complex. Prescott Bush (George W.’s grandfather) was a banker with ties to early petroleum companies and even controversial dealings in the WWII era. George H.W. “Poppy” Bush (the father) ventured into the Texas oil fields in the 1950s, co-founding Zapata Petroleum and later Zapata Off-Shore, specializing in offshore drilling . But oil was only one arena. Declassified files and investigative reporting suggest Bush Sr. also had a clandestine career in the CIA well before he officially became its Director in 1976.

In fact, an FBI memo from November 1963 (just after JFK’s assassination) intriguingly refers to a briefing given to “Mr. George Bush of the Central Intelligence Agency,” indicating that Bush – then ostensibly just a private oilman – was involved with CIA covert operations in the early ’60s . A source close to the intelligence community later confirmed that Bush started working for the CIA in 1960 or 1961, using his oil business as a cover for clandestine activities . (Bush Sr., when asked, gave a classic non-denial denial, claiming he was busy “in the independent oil business” at the time .) Whether in the Caribbean or elsewhere, Bush Sr.’s dual identity – oil executive and spy – exemplified how U.S. petroleum interests and intelligence operations often went hand in hand during the Cold War.

By the 1970s, Bush Sr. would helm the CIA and later, as Vice President and President in the 1980s-90s, play a key role in Middle East geopolitics. He was deeply involved in covert operations (from the Iran-Contra affair to clandestine support for mujahideen in Afghanistan – which, not coincidentally, sits strategically near vast oil and gas reserves in Central Asia). As President in 1991, George H.W. Bush led Operation Desert Storm to expel Iraq from Kuwait – a war widely viewed as protecting global oil supplies and the sanctity of borders in the oil-rich Persian Gulf. Though Bush stopped short of toppling Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein in 1991, many in his orbit – including Dick Cheney and Paul Wolfowitz – believed the job was unfinished. Bush Sr. famously spoke of a “New World Order” emerging after the Gulf War, with the U.S. at the apex.

George W. Bush (the son) inherited this mantle. Though lacking his father’s polish or deep resume, Bush Jr. was surrounded by many of his father’s lieutenants and benefactors. Halliburton, the oil services giant once run by Dick Cheney (who became W’s Vice President), and the Saudi royal family – lifelong allies of the Bushes – were at the apex of influence. It’s even noted that on the morning of 9/11, Bush Sr. was meeting with members of the bin Laden family (yes, Osama’s kin) at an investment conference in D.C., illustrating how interwoven the Bush-Saudi-bin Laden relationships were (through business consortiums like the Carlyle Group).

The younger Bush’s personal background also intertwined with oil: he had co-founded Arbusto Energy in West Texas and later led a company called Harken Energy. These ventures were modestly successful at best, but they cemented Bush’s identity as an “oil man.” More importantly, Bush Jr.’s rise to power was bankrolled by oil and defense interests, and his worldview – lacking nuance – was heavily influenced by hawkish advisors who cut their teeth in Bush Sr.’s circles. As we’ll see, these advisors were waiting for an opportunity to remake the world map.

In sum, the Bush family ethos combined old-school CIA covert thinking with petro-capitalism. The father’s whispered legacy to the son was an implicit doctrine: American supremacy must be upheld, and the oil must flow – by covert action if possible, by open war if necessary. So when George W. Bush took office in January 2001, flanked by Cheney, Rumsfeld, Wolfowitz and other hardliners, the stage was set. What they needed was a catalyst – a unifying event to galvanize the public for the wars and grand strategy they had in mind. According to one of their own policy blueprints, they were looking for a “new Pearl Harbor.”

The PNAC Blueprint: In Search of a “New Pearl Harbor”

One year before 9/11, a neoconservative think tank called Project for a New American Century (PNAC) eerily predicted the necessity of a catalyzing tragedy. PNAC, founded in 1997 by figures like William Kristol and Robert Kagan, championed an unabashedly imperial vision: the U.S. should assert unchallenged military dominance and pre-emptively deal with any threats to its hegemony. In September 2000, PNAC produced a report titled “Rebuilding America’s Defenses.” In its dry bureaucratic prose lies a chilling statement: “the process of transformation, even if it brings revolutionary change, is likely to be a long one, absent some catastrophic and catalyzing event – like a new Pearl Harbor.” .

This quote wasn’t an idle musing. Many PNAC members soon joined the Bush Jr. administration in 2001, including Vice President Cheney, Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, Deputy Defense Secretary Paul Wolfowitz, and others. They entered office with a laundry list of geopolitical “to-dos” – chief among them the removal of Saddam Hussein in Iraq, which PNAC had openly urged in letters to President Clinton in the late 1990s. Iraq, Iran, North Korea were dubbed the “Axis of Evil” by Bush, reflecting PNAC’s worldview. What they lacked was public justification to launch the wars required to reshape the Middle East and secure American primacy.

September 11, 2001 gave them that justification. The 9/11 attacks were immediately seized upon as the “Pearl Harbor” moment to implement pre-existing plans. While the debate rages as to how much foreknowledge or complicity figures in the Bush administration had regarding the attacks (the spectrum runs from criminal negligence to outright inside job theories), what’s clear is that post-9/11, the Bush team moved with lightning speed to capitalize on the tragedy . They pushed through the PATRIOT Act at home and the “War on Terror” abroad – a blank-check doctrine for global military intervention.

Notably, Iraq was targeted from day one, even though Iraq had nothing to do with 9/11. Former Treasury Secretary Paul O’Neill later revealed that removing Saddam was a topic on the table in National Security Council meetings well before the attacks, and Defense Secretary Rumsfeld on 9/11 itself asked for plans to strike Iraq. This disconnect – attacking a country unrelated to the Al Qaeda plot – is explainable only in light of the grand strategy Bush’s team had banked on. In their eyes, 9/11 provided the excuse to do what they already wanted to do: overthrow regimes that were obstacles to U.S. dominance (and to the petrodollar system) and to send a message that American might would secure the global order in the new century.

It was a strategy born in think-tanks and inherited from the elder Bush’s Gulf War era. Indeed, some analysts like journalist John Pilger argued that the Bush administration “used the events of September 11 as an opportunity to capitalize on long-desired plans” outlined by PNAC . The younger Bush, whose instincts were more parochial, was guided by these ideologues – effectively doing “as his daddy (and his dad’s circle) told him,” strategically speaking. The result was a series of interventionist campaigns, which we’ll examine next, each with a significant undercurrent of oil and dollar geopolitics.

Petrodollar Wars: Iraq, Libya, and Others Who Challenged the Dollar

The post-9/11 American wars can be viewed through many lenses – fighting terrorism, spreading democracy, seizing oil fields – but one powerful perspective is that they were wars to defend the petrodollar system. Countries that threatened to sell their oil in currencies other than the U.S. dollar found themselves in Washington’s crosshairs. This is not a coincidence, given how vital dollar-priced oil is to U.S. economic hegemony. Let’s look at a few key cases:

Iraq (2003): Saddam Hussein’s Iraq was a charter member of the “Axis of Evil” in Bush’s rhetoric. But why was Iraq so targeted, beyond vague claims of WMDs and tyranny? One little-noted fact: In October 2000, Saddam *announced that Iraq would no longer accept U.S. dollars for its oil; henceforth, Iraqi oil under the UN Oil-for-Food program would be sold in euros . At the time, the euro was new and weak – Saddam’s move was derided as economically foolish . But by early 2003, after two years of euro appreciation, Iraq had profited hundreds of millions by dumping the “currency of the enemy” (USD) for euros . More alarmingly for Washington, Iraq had unhinged itself from the petrodollar. It set a precedent that others (Iran, Venezuela) were openly musing about following . The Bush administration’s invasion of Iraq in March 2003 swiftly achieved regime change – and one of its first acts was to revert Iraq’s oil sales back to dollars. The “petro-euro” experiment was decisively ended . Iraq’s fate sent a clear warning: no OPEC member would be allowed to break the dollar monopoly on oil without consequences.

Libya (2011): Muammar Gaddafi’s oil-rich Libya had long been a thorn in the West’s side, though by the 2000s relations were improving. But Gaddafi was harboring ambitious monetary plans. He had proposed a Pan-African gold dinar currency – a single African currency backed by gold – which could be used for oil trade, bypassing the dollar and euro. In early 2011, as the Arab Spring hit Libya, Gaddafi was reportedly on the verge of launching this gold-backed dinar and was urging other African and Middle Eastern nations to join in pricing oil in this new currency . This move, had it succeeded, directly threatened the petrodollar system (and even the euro to some extent). A NATO-led intervention quickly materialized under the banner of protecting Libyan civilians in a “humanitarian” war. Internal emails later revealed that French officials pushed for intervention in part to thwart Gaddafi’s currency plan and secure access to Libyan oil for themselves . After NATO’s bombing campaign and a rebel uprising, Gaddafi was killed, and the project for a gold dinar died with him. Libya soon descended into chaos, but oil once again traded in dollars. As researcher Ellen Brown pointed out, both Iraq and Libya had made bold moves against the petrodollar shortly before they were attacked .

Iran: Iran had quietly been exploring oil trade in non-dollar currencies since the early 2000s. The country opened an “Iranian Oil Bourse” in 2008, explicitly to allow oil trade in euros, yen, or other currencies. Tehran also began conducting more of its petroleum trade in euro, yuan, and barter deals (especially as U.S. sanctions on Iran’s banking sector tightened). While Iran wasn’t invaded (arguably because it’s a much bigger and tougher target than Iraq or Libya), it has been under severe U.S.-led sanctions for decades. Those sanctions intensified whenever Iran made moves to bypass the dollar. It’s a financial war rather than an outright shooting war – but the goal is similar: to punish deviation from the dollar system. Iranian officials have openly claimed that their push to price oil in other currencies is one reason they are in Washington’s crosshairs.

Venezuela: Another oil state that challenged dollar hegemony, Venezuela under Hugo Chávez began in the 2000s to seek alternatives to the dollar. Venezuela discussed shifting oil exports to be priced in Euros or a new regional currency. In 2018, Nicolás Maduro even launched the “Petro” cryptocurrency, claimed to be backed by Venezuela’s oil reserves, as a way to circumvent U.S. sanctions and the dollar. These moves coincided with relentless U.S. economic sanctions and attempts to isolate and undermine the Venezuelan government. Like Iran, Venezuela hasn’t seen a U.S. invasion, but it has experienced covert support for coups and constant economic warfare – some would argue, for daring to question the dollar’s monopoly as much as for its domestic politics.

Syria: Syria made itself a target primarily for other geopolitical reasons (civil war, strategic location, alliance with Iran/Russia). But it’s worth noting Syria had also discussed dropping the dollar in the late 2000s for oil transactions. By 2006, Iran, Syria, and Venezuela were talking about pricing oil in euros. By coincidence or not, Syria in 2011 faced a devastating rebellion/civil war in which the U.S. and Gulf states funded opposition groups. The reasons are complex (Syria’s alliance with Iran, pipeline routes, etc.), but maintaining Western influence over energy corridors was certainly in the mix.

This pattern – “attempt to stray from the dollar, get hit by U.S. intervention or sanctions” – has not gone unnoticed by other nations. Russian President Putin observed in 2011 (after Libya) that Gaddafi’s gold dinar idea was a major factor in his overthrow. Likewise, when Saddam was captured, one of the first things the new U.S.-backed government did was re-link Iraq to the dollar. It’s as if the dollar truly is the bedrock of U.S. empire: undermine it at your peril.

Of course, oil was not the only factor in these conflicts. Geopolitics is multi-layered, and policymakers certainly had multiple motives. But oil and the dollar’s primacy provided a consistent strategic backdrop. American leaders knew that control over oil – and ensuring it is traded in dollars – meant control over the lifeblood of the global economy. As an infamous Dick Cheney 1999 speech about the Middle East oil put it: “the good Lord didn’t see fit to put oil and gas only where there are democratic regimes friendly to the United States.” So they dealt with unfriendly regimes in other ways.

The Petrodollar Feedback Loop: Dollar, Debt, and Military Force

By waging wars and toppling regimes in oil-rich states, the U.S. wasn’t acting on whim – it was reinforcing a self-perpetuating feedback loop that kept its economy humming and its rivals in check. How exactly does this petrodollar feedback system work? In simplified form:

Global oil trade in USD – Thanks to the petrodollar system, countries around the world must buy dollars to pay for oil. This creates an artificial demand for dollars abroad. For example, a German importer or an Indian utility needs USD to purchase crude oil on international markets. This constant demand props up the dollar’s value.

Investment of surplus back into the U.S. – Oil-exporting nations, especially in the Gulf, accumulate vast dollar surpluses. They have historically recycled these petrodollars into U.S. assets, particularly U.S. Treasury bonds, stocks, real estate, and weapons . In the 1970s, Kissinger and Nixon explicitly encouraged Saudi Arabia and others to invest in Treasuries, creating a steady foreign demand for U.S. government debt. This allowed America to run large budget deficits (for defense build-ups, tax cuts, etc.) without crashing its currency or causing high inflation – the excess dollars were soaked up by eager foreign investors and central banks. One researcher noted this recycling “propped up U.S. budget deficits and helped finance Cold War expenditures.”

“Exorbitant Privilege” and debt tolerance – Because of (1) and (2), the U.S. dollar gained a unique status. Countries held dollars as their reserve currency – by the 2000s, over 60% of global foreign exchange reserves were in USD. Oil exporters kept buying U.S. bonds (which kept U.S. interest rates low). The U.S. could print dollars (or Treasury debt) freely to pay for imports and military adventures, without the usual penalty of devaluation that other countries would face. As a French minister famously quipped in the 1960s, this was an “exorbitant privilege.”

Military enforcement – Here’s the twist: the entire system relies on strategic confidence. Why do oil producers accept dollars – essentially paper or digital entries – in exchange for real commodities? In part because they can use those dollars to buy American goods and assets, but also because the U.S. provides them security. The U.S. military umbrella protects allied regimes (like the Saudi monarchy, which might not survive without U.S. support) . And conversely, any regime that defies the rules can be threatened by that same military might. Thus, U.S. military dominance both upholds the petrodollar order and is funded by it – a reinforcing cycle.

Geopolitical leverage – With the world economy so dollar-dependent, the U.S. can sanction adversaries by cutting off access to dollars (as seen with Iran, Russia, etc.), crippling their ability to trade oil or anything on global markets. Additionally, countries drowning in dollar-denominated debt (many developing nations took out loans payable in USD) remain beholden to U.S.-led institutions like the IMF. This debt web was another form of control, enabled by the dollar’s ubiquity.

The petrodollar feedback loop created a paradigm where the U.S. could consume far more than it produced (running persistent trade deficits) and still see its currency stay on top. Foreigners essentially funded American prosperity by sending back the dollars they earned. It also funded American militarism; oil wealth from Saudi or Chinese export earnings from manufacturing would be lent to Washington, which spent trillions on its military and wars – which in turn secured the global trade routes and friendly regimes that kept the dollars flowing.

Economists and historians have described this system as a new imperial arrangement: unlike old empires that extracted tribute in gold or resources, the U.S. empire extracts tribute in the form of dollar investments. It prints dollars, other nations have to hold them and give value to them by trading real goods for them. As long as the world needed dollars, the U.S. could never “go bankrupt” in the normal sense – it could always pay its bills by issuing more of its own currency, which everyone from central banks to oil traders would accept. This is why preserving the dollar’s supremacy became a matter of national security. It wasn’t just economic theory; it underpinned America’s status as sole superpower after 1991.

However, feedback loops can become vicious cycles. Over decades, the petrodollar fueled excess: the U.S. government accumulated enormous debt (public debt exceeded $30 trillion by 2020s) confident that others would buy it; American consumers and corporations indulged in cheap credit; Wall Street grew addicted to foreign capital inflows. Meanwhile, oil-exporting countries faced their own distortions – “oil curse” economies, petrodollar-funded corruption, and, in some cases, resentment from populaces that saw their leaders as U.S. puppets. Environmentally, tethering the world economy to oil delayed a transition to renewables, worsening climate change.

By the late 2010s, cracks in the system were showing: the shale oil boom made the U.S. itself a major oil exporter (lessening its need for Middle East oil, arguably), but new challengers were rising. China’s economy was rivaling America’s, and China was not keen on permanent dollar domination. Russia was reasserting itself and tired of playing by U.S. financial rules. In fact, starting around 2014, Russia and China began conducting more trade in rubles and yuan, cutting the dollar out. The U.S.’s own behavior – using the dollar-centric financial system as a weapon (sanctioning banks, cutting off SWIFT access, seizing foreign reserves – as it did to Russia in 2022) – ironically motivated even allied nations to seek alternatives to reduce their vulnerability.

By 2020, the dollar’s share of global reserves had slipped to ~59% (down from ~71% in 1999) . The petrodollar still reigned, but it was no longer unchallenged. A feedback loop that once seemed unbreakable was facing entropy.

The New Challengers: Toward a Multipolar Commodity-Digital Order

If the petrodollar system is inching toward its twilight, what might replace it? We are entering a multipolar world – economically and technologically. Several emerging forces and ideas could shape a new “commodity order” or value order in the coming decades:

Eastern Blocs and the Petro-yuan: China and Russia, along with other BRICS nations (Brazil, India, South Africa, etc.), have openly discussed creating alternatives to U.S.-centric finance. China, the world’s largest oil importer, has been gradually increasing oil purchases priced in renminbi (yuan). It helped launch a yuan-priced oil futures market in Shanghai in 2018. More recently, China developed a digital yuan (e-CNY) – a central bank digital currency – in part to facilitate trade outside the dollar system. In 2023, China and Gulf countries conducted their first cross-border oil trades settled in digital yuan, a milestone that hints at a future “petro-yuan” for Chinese trade . While the dollar still dominates oil transactions (about 80% of global oil sales are in USD ), the trend is shifting. Analysts note the petrodollar’s decline “isn’t a question of if, but when” in the Persian Gulf, as rapid changes in finance and geopolitics drive diversification . That said, even Chinese economists admit the yuan is unlikely to fully replace the dollar; instead, a dual system may emerge , with the yuan gaining regional prominence (especially for trade among Asia, Russia, the Middle East), while the dollar gradually loses market share.

Resurgence of Gold and Commodity Baskets: In times of uncertainty, hard assets like gold often make a comeback. Central banks, notably those of Russia and China, have been buying gold like crazy in the last decade, partly as insurance against dollar turmoil. There are talks (some floated by Moscow) of a BRICS-issued reserve currency possibly linked to a basket of commodities or gold. The idea of a commodity-backed currency harks back to older concepts (even Henry Ford in 1921 proposed an “energy currency” based on commodity units!). It would mean, for example, a new international trade unit that could be redeemed for a mix of oil, gas, grain, and metals – reflecting the real stuff of value. Such a scheme is complex and not imminent, but it shows the craving for something more tangible than the U.S. Federal Reserve’s promises. Even energy-backed cryptocurrencies have been proposed: for instance, Venezuela’s ill-fated Petro coin was theoretically tied to a barrel of oil. Others have suggested “carbon coins” or “electricity tokens” that represent a certain amount of energy. The underlying notion is to align currency with commodities that nations universally need – energy, food, raw materials – which could form a new reserve asset mix less prone to one country’s politics.

Compute Power as the New Oil: One fascinating speculative idea is that in the 21st century, computing power (especially for AI) will become a foundational commodity, much like oil was in the 20th. As one futurist framework suggests, “a nation’s credibility will be determined by how much it can compute… A country with robust semiconductor and AI capabilities will be able to anchor its currency with computational resources.” This “compute-backed economy” vision sees AI and cloud computing capacity analogous to oil reserves or gold in terms of strategic value. If AI drives productivity and prosperity, then controlling AI infrastructure (chips, data centers, algorithms) becomes as geopolitically crucial as oil wells and pipelines. Already, tech giants like Google, Microsoft, and Amazon Web Services wield near-monopoly power over global cloud computing – arguably “AI monopolies” that could one day leverage their platforms to issue digital currencies or influence monetary flows. Imagine an “AI-backed token” where the collateral is computing time or access to large language model services. This may sound far-fetched, but so did petrodollars in 1945. The arms race over semiconductor chips (US vs China on export controls) shows that states view compute prowess in zero-sum, security terms. In a sense, data centers are the new oil rigs, and algorithms the new refineries. It’s conceivable that alliances or companies might create compute-backed stablecoins – tokens redeemable for X amount of cloud compute or AI API calls – which AI-driven economies would readily accept. While not mainstream yet, experiments are underway. Projects in the crypto world talk of tokenizing computing resources, and some DeFi platforms offer “compute-backed loans” . If AI truly becomes the engine of the economy, then the currency that underpins that economy might logically be tied to AI in some way.

Digital Currencies & Decentralized Finance: The proliferation of cryptocurrencies and blockchain-based finance is another dimension. Bitcoin, in particular, has been dubbed “digital gold” and even an energy currency (since Bitcoin mining converts electricity into token value). Some see Bitcoin as a hedge against dollar debasement – indeed, countries like El Salvador adopted it as legal tender, and some politicians in dollar-skeptic countries advocate holding Bitcoin in reserves. However, crypto is far too volatile and unregulated (for now) to serve as a global reserve currency. More likely is the integration of Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs). Over 100 countries are exploring CBDCs – effectively digital versions of fiat money. The digital yuan is the furthest along of major economies; the U.S. is studying a “digital dollar.” In a future scenario, major powers might transact directly via CBDC networks without needing SWIFT or correspondent banks, reducing the chokehold of the dollar-based system. A digital yuan could be used in Belt and Road Initiative projects or oil deals between China and Middle East, with smart-contracts enforcing terms. A digital dollar could maintain some relevance, but if trust erodes, participants have easier on-ramps to alternatives than in the analog past.

Resource-backed Tokens & Carbon Credits: Alongside energy tokens, the climate change era might spur carbon credit currencies or water/resource-backed tokens. For example, some have floated an “Energy Backed Currency Unit (EBCU)” linked to a standardized amount of energy (like a megawatt-hour) . This would incentivize cleaner energy production: countries producing surplus renewable energy would effectively mint currency. While still theoretical, such ideas underscore a drive to tie value to the real physical limits of our planet (energy, emissions) rather than political fiat. They also could form a multilateral commodity standard – not relying on one commodity (like only gold or only oil) but a basket that nations agree on.

In short, the future likely won’t be a single new hegemonic currency replacing the dollar outright, but rather a multipolar matrix. The dollar may remain important but lose monopoly; the euro will hold regional sway; the yuan will rise in Asia; gold will lurk as a trust-anchor; and digital assets – whether Bitcoin, CBDCs, or others – will play a role in settlements. We might see a world where several commodities and tech resources underwrite trust. For example, a global trade could be invoiced in a digital SDR-like basket that includes dollars, yuan, a gram of gold, and a kWh of energy – all tokenized on a blockchain.

This pluralism could reduce the ability of any one country to unilaterally finance wars or sanction others by control of currency flows. But it also heralds instability and competition. The petrodollar era had many ills, but it provided a (coercively maintained) stability. A post-petrodollar era might be more free but also more volatile, unless new institutions emerge to manage this complexity.

After the Empire – Reflections on What’s Next

The saga of “oil, empire, and ego” that we’ve traced – from Nixon and Kissinger’s petrodollar gambit, through the Bush family’s entanglements, to the war on terror and beyond – reveals how deeply our world was shaped by the pursuit of dollar supremacy. The U.S. built a de facto empire not by colonizing territory, but by anchoring the world’s wealth to its currency and enforcing that system through both diplomacy and force. Trillions of dollars, m illions of lives, and untold opportunities for global cooperation were sacrificed at this altar. As the title suggests, 9/11 and the ensuing wars were not random – they fit into a pattern. George W. Bush’s actions following in his father’s footsteps were part of a continuum of policy aimed at prolonging the “unipolar moment” when America could dictate terms unchallenged, largely by virtue of controlling the world’s monetary lubricant (the dollar tied to oil).

But no empire lasts forever, at least not in the same form. We are likely living through the early days of the dollar’s relative decline and the messy birth of a new order. Ironically, by overplaying its hand – with Iraq, with aggressive financial sanctions, with ballooning debt – the U.S. accelerated calls for an alternative to the dollar system. The very wars meant to secure American hegemony have sapped its moral authority and economic strength. And climate imperatives will eventually force a weaning off the oil addiction that undergirded the petrodollar arrangement.

So what might replace it? Perhaps a “Commodity Commons” – a system where value is grounded in a mix of critical resources (energy, metals, food, compute) and managed by a consortium of major powers. Technology will be pivotal: currency could become programmable, smart, and infused with AI (imagine AI managing reserve allocations for optimal stability). We may even witness a strange convergence of old and new – gold and Bitcoin held side by side in national reserves, or oil contracts settled in digital yuan tokens, or tech companies issuing coins backed by their cloud infrastructure.

For the average person, these high-level shifts can seem abstract. But they have real consequences: currency values affect the price of everything, and wars for oil or dominance affect families and futures everywhere. A fairer multipolar system could reduce the temptation for any single nation to “pave the world” with war in order to prop up its currency. However, if the transition is chaotic, it could also spark new conflicts – e.g., currency wars, cyber wars, or an AI arms race to see who controls the new “oil”.

The story of the petrodollar’s rise and (potential) fall is a cautionary tale of interdependence. The U.S. tied its fortunes to oil and militarism; now the world is grappling with the fallout. The next system, whatever it is, will hopefully tie fortunes to more sustainable and equitable anchors – be it clean energy, shared technology, or baskets of diverse values. As we stand on the brink of this transition, looking back at the last 50 years, we can see how “oil, empire, and ego” indeed built the dollar’s throne and wrought havoc in the process. The task now is to ensure that what comes next – this new commodity order in a digital age – learns from those mistakes and fosters a more stable and cooperative global economic order.

In the end, perhaps Bush did “do 9/11” in the sense that his administration willingly lit the fuse that blew up the old world order – but the subsequent explosion may yet force a rebirth, one not directed by any one daddy or dynasty, but by a collective reckoning with the past and a reimagining of value beyond oil and war.

Or idk maybe it was him and maybe his dad did plan it. Idk tho.

Sources and References

Books & Academic Sources:

Clark, William R. Petrodollar Warfare: Oil, Iraq, and the Future of the Dollar. (New Society Publishers, 2005)

Perkins, John. Confessions of an Economic Hit Man. (Berrett-Koehler, 2004)

Engdahl, F. William. A Century of War: Anglo-American Oil Politics and the New World Order. (Pluto Press, 2004)

Reports & Articles:

Project for a New American Century (PNAC). “Rebuilding America’s Defenses” (2000). Link

Escobar, Pepe. “Why the Petrodollar is a Dying Animal.” Asia Times, 2018. Link

Hudson, Michael. “Super Imperialism: The Origin and Fundamentals of U.S. World Dominance.” Link

Declassified Documents & Investigations:

National Archives. Nixon Tapes & Declassified Kissinger–Saudi Arabia Agreements, 1974. Link

FBI Documents linking George H.W. Bush to CIA operations, 1963 memo. Link

Investigative Journalism & Independent Sources:

Brown, Ellen. “Libya: All About Oil, or Central Banking?” Global Research. Link

Corbett Report. “How Big Oil Conquered the World.” Link

Whitney Webb. “The Bush Family’s Ties to Saudi Arabia.” MintPress News. Link

Data & Visuals: