Alan Turing and His Enigma: The Man Who Cracked the World’s Code While Hiding Himself Away

Think you can crack the code?

This passage is dedicated to a very special person in my life. Through this passage is dispersed an encrypted message explaining for whom this passage is dedicated to and why. Decrypting all five words or characters will require varying levels of cryptography skill, and varying levels of expertise across topics. The full phrase is encoded in the first five distinct sections. You should also use the substack site itself to peruse the data. Good luck.

Prologue: The Hidden Genius

In the pre-dawn chill of the English countryside, a strange factory hummed to life. It was not a factory of steel or textiles, but of thought. At Bletchley Park, a sprawling Victorian estate in Buckinghamshire codenamed "Station X," the fate of the free world was being weighed, one decrypted message at a time.1 Cables snaked across makeshift tables inside spartan wooden huts, some of which were so hot and noisy from the machinery that their occupants dubbed them the "Hell-Hole".2 The air, thick with the scent of ozone and stale tea, vibrated with the incessant, rhythmic clicking of electromechanical relays—the sound of German secrets being systematically dismantled.

This was the domain of the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS), a motley but brilliant assembly of minds recruited in absolute secrecy. They were a curious mix: "tweedy professors" and academics poached from the halls of Oxford and Cambridge, linguists, chess grandmasters, and, making up the vast majority of the nearly 10,000-strong workforce, thousands of civilian women from the Women's Royal Naval Service (Wrens) and the Women's Auxiliary Air Force (WAAFs).1 They were the unseen army, performing the relentless, often tedious, intellectual labor that underpinned the entire Allied intelligence effort. The atmosphere was a bizarre paradox: a "college-campus-like setup" with a bustling Recreational Club, amateur dramatics, and scholarly debate, all nested within a fortress of state-enforced silence.7

At the heart of this intellectual crucible was Alan Mathison Turing, a man whose mind was the ultimate decryptor. He was the principal architect of the machines whose clicking filled the huts, the logician who saw the path through a cryptographic labyrinth that the German high command believed was impenetrable. His intellect was a "universal machine," a national treasure capable of decoding not just messages, but the enemy’s very intentions. Yet, Turing himself was the ultimate cipher. His identity as a homosexual man was a secret he was forced to encrypt, a truth he had to conceal from the very society he was instrumental in saving. The rigid, punitive "codes" of morality and law that governed 1940s Britain were, for him, as formidable and dangerous as the German cipher he was tasked to break.10 The environment of Bletchley Park itself was a perfect microcosm of his life's central conflict: a space of extraordinary intellectual freedom contained within a framework of absolute state control. The state that harnessed his non-conformist genius to break an external enemy's code would, in a few short years, use its own unbending codes of law and morality to break him for his personal non-conformity.

Alan Turing's life represents a profound and tragic collision between individual genius and societal prejudice. His revolutionary breakthroughs in cryptanalysis and computer science, which were instrumental in securing Allied victory and saving millions of lives, were achieved within a state that simultaneously celebrated his mind and criminalized his very being. This persecution, born of institutionalized bigotry, not only led to his personal destruction but also stands as a stark historical lesson on the catastrophic cost of intolerance—a cost measured not only in one man's suffering but in the lost potential of a mind that could have propelled human progress even further into the future he had already begun to invent.

Breaking the Enigma: The Universal Machine of War

The German Enigma machine was the cornerstone of the Axis powers' secure communications. To the Allied forces, it was a black box that swallowed vital intelligence, leaving them blind to enemy movements and intentions. To its creators, it was a masterpiece of electromechanical engineering, a guarantor of secrecy they believed to be, for all practical purposes, unbreakable.12 Breaking it would require more than ingenuity; it would demand a fundamental rethinking of what a machine could do.

Technical Overview of Enigma: The "Unbreakable" Machine

At its core, the Enigma was an elegant, typewriter-like device that implemented a brutally complex polyalphabetic substitution cipher.13 When an operator pressed a key, an electrical current passed through a series of scrambling components before lighting up a lamp corresponding to the encrypted letter. The genius of the machine lay in the fact that this scrambling pathway changed with every single keystroke, preventing the frequency analysis that had doomed simpler ciphers. This complexity was built upon three key components:

Rotors: The heart of the Enigma was a set of interchangeable rotors, or Walzen. These were wired discs that would rotate in a manner similar to a car's odometer.15 Each rotor contained a unique and complex internal wiring that mapped each of the 26 input contacts to a different output contact. With each key press, the rightmost rotor would advance one position. Periodically, it would trigger the middle rotor to turn, which in turn would eventually advance the leftmost rotor.17 This constant motion meant that typing the letter 'A' twice would produce two different ciphertext letters, creating a cipher with an astronomically long period before the substitution pattern repeated. The German Army and Air Force typically selected three rotors from a pool of five, which alone provided 60 different starting arrangements (

5×4×3).12Reflector (Umkehrwalze): After passing through the three rotors, the electrical signal hit a unique, non-rotating wheel called the reflector. Its job was to take the signal and send it back through the rotors along a different path.19 This design was clever, as it ensured reciprocity: if an Enigma machine set to a specific key encrypted 'A' as 'T', then typing 'T' on an identically set machine would decrypt it back to 'A'.12 This simplified operation but introduced a critical, and ultimately fatal, cryptographic flaw: because of the reflector's paired wiring, no letter could ever be encrypted as itself.14 An 'A' could never become an 'A', a 'B' never a 'B'.

Plugboard (Steckerbrett): The final layer of complexity, and the one on which German confidence most heavily rested, was the plugboard. This was a patch panel on the front of the machine that allowed the operator to use cables to swap pairs of letters before the signal entered the rotors and after it left them.17 By using ten cables to swap ten pairs of letters (a typical configuration), the number of possible settings skyrocketed. This single component added over 150 trillion combinations to the key space, leading German cryptanalysts to believe that even if the rotor system were somehow compromised, the plugboard would guarantee the machine's security.12

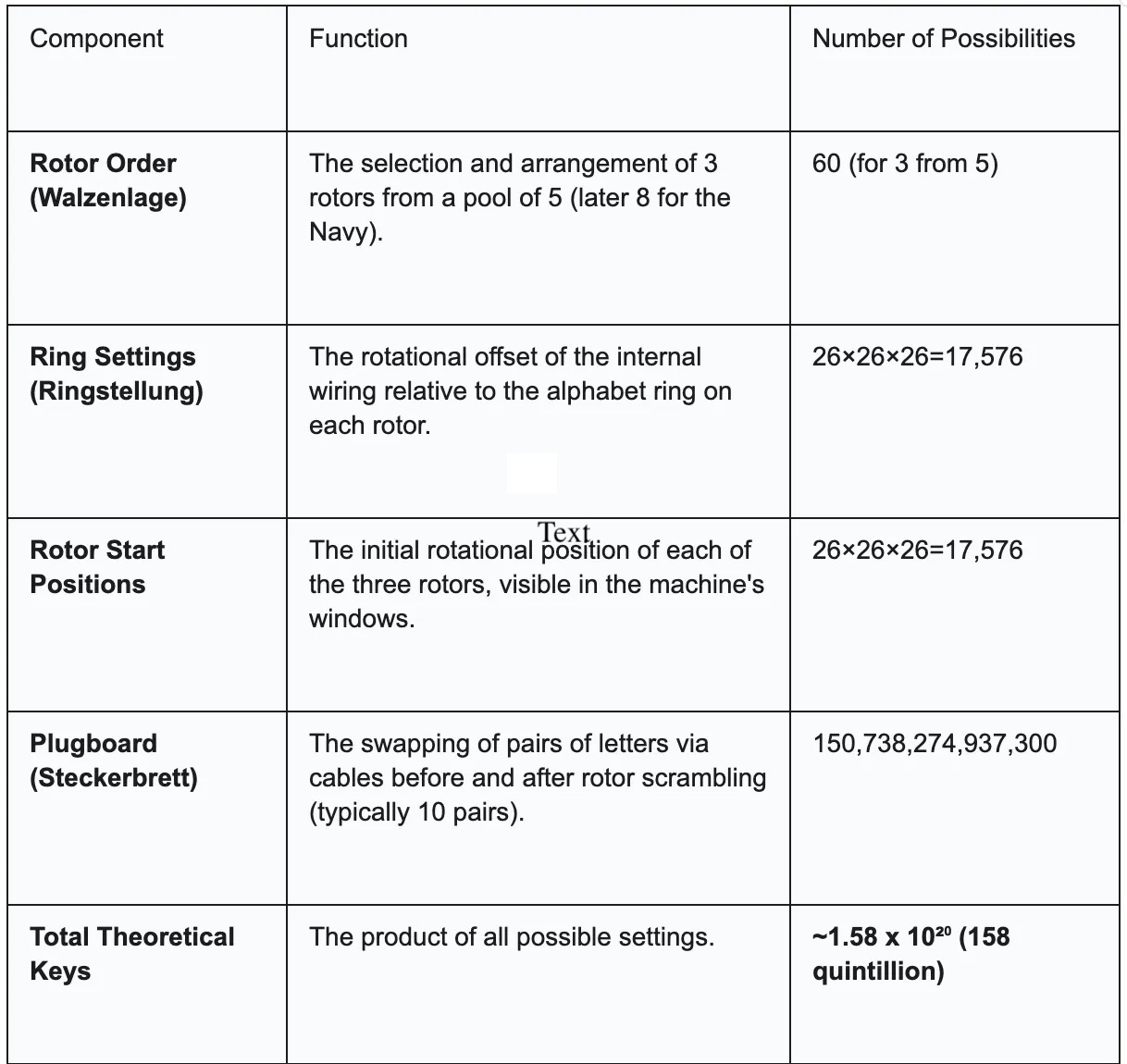

The combinatorial result of these layers was staggering. The choice of rotors, their order, their initial starting positions, the adjustable ring settings on each rotor, and the plugboard connections created a keyspace so vast it defied imagination. Precise calculations vary, but a conservative estimate for the number of possible daily keys for the Wehrmacht Enigma is approximately 1.58×1020, or 158 quintillion.12 A more expansive calculation puts the total number of states at over

1023.12 With the keys being reset every 24 hours, a brute-force attack—testing every possible combination—was not just impractical; it was physically impossible with the technology of the era.21

Turing's Innovations: Logic over Brute Force

The German confidence in Enigma's security was based on its sheer combinatorial size. They assumed any attacker would have to engage in a war of permutation, trying every key one by one. Alan Turing's genius was to understand that this was the wrong way to conceptualize the problem. He did not try to build a machine to out-calculate Enigma; he designed a machine to out-think it. His approach was not one of brute force, but of elegant, mechanized logic.

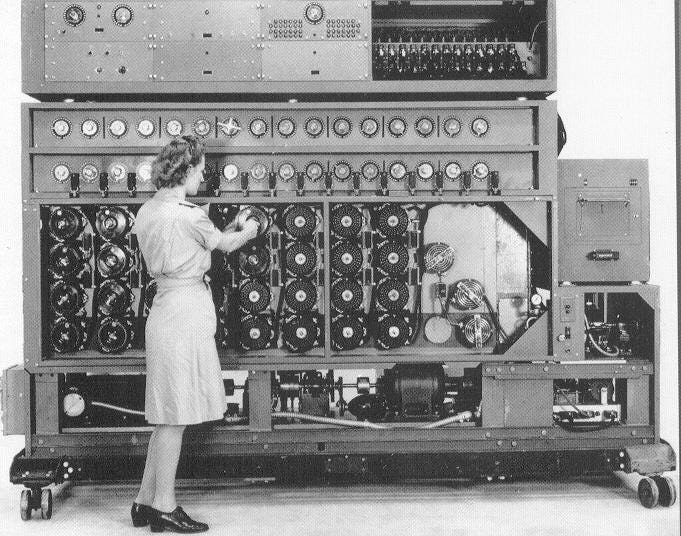

The foundation of this approach was the Turing-Welchman Bombe, an electromechanical device developed at Bletchley Park that built upon earlier Polish designs (the bomba kryptologiczna).23 The Bombe was not a decryptor in the modern sense. Its purpose was to rapidly search for the correct Enigma settings for a given day's traffic.16 Its operation was predicated on two things: a human procedural error and Enigma's own fatal flaw. The error was the German operators' frequent use of predictable phrases, such as standard greetings or weather reports ("Wetterbericht"). The Bletchley codebreakers could often guess that such a phrase, which they called a "crib," would appear somewhere in an encrypted message.23

The Bombe's brilliance lay in how it exploited the Enigma's reflector flaw—that no letter could encrypt to itself. A codebreaker would take a crib and align it against a stretch of ciphertext, looking for a possible match. If, at any position, a letter in the crib was the same as the letter in the ciphertext (e.g., the 'E' in the crib aligned with an 'E' in the ciphertext), that alignment was logically impossible and could be immediately discarded.14 Once a plausible crib-ciphertext alignment was found, it formed a "menu" of logical relationships that could be fed into the Bombe.

The Bombe itself consisted of dozens of sets of Enigma rotors, effectively simulating multiple Enigma machines working in parallel.26 It would be configured according to the menu and then set to run. As the rotors spun at high speed, the machine tested a hypothesis about the rotor order and starting positions. It was not trying to decrypt the message, but rather to find a setting that was

logically consistent with the relationships in the crib. If a particular setting led to a logical contradiction—such as requiring the letter 'A' to be plug-cabled to both 'S' and 'P' simultaneously—the machine would reject that setting and continue its search. When the machine found a rotor configuration that did not produce any logical contradictions, it would stop. This "stop" indicated a potential solution, which

—

would then be passed to the Wrens to test on a British Typex machine, hopefully revealing the day's key.23 The process was made vastly more efficient by a crucial refinement from mathematician Gordon Welchman. His "diagonal board" was an additional wiring panel that exploited the reciprocal nature of the plugboard connections, dramatically reducing the number of false stops and making the Bombe a truly effective industrial codebreaking tool.24

This conceptual leap—from permutation to deduction, from calculation to logic—was the essence of Turing's contribution. It was a physical manifestation of the abstract theories he had developed in his seminal 1936 paper, "On Computable Numbers," which introduced the concept of a "universal Turing machine".27 This theoretical construct, a machine capable of simulating any other machine's logic, laid the groundwork for the modern stored-program computer. His work at Bletchley was a powerful, real-world application of these principles. After the war, he would go on to design the Automatic Computing Engine (ACE), one of the first complete specifications for a general-purpose digital computer, cementing his legacy as the father of both theoretical computer science and artificial intelligence.28

Impact on WWII: Turning the Tide

The intelligence derived from the broken Enigma messages, codenamed "Ultra," had a decisive impact on the outcome of the Second World War. Historians, and wartime leaders like Winston Churchill, have estimated that the work at Bletchley Park shortened the war by at least two to four years, saving what could amount to millions of lives.

Nowhere was this impact more profound than in the Battle of the Atlantic. In the early years of the war, German U-boats, hunting in "wolf packs," were sinking Allied supply ships at an unsustainable rate, threatening to sever Britain's lifeline to the United States and Canada.30 The decryption of the more complex German Naval Enigma, a feat spearheaded by Turing and his team in Hut 8, was a turning point. Ultra intelligence allowed the Admiralty to track U-boat patrol lines with astonishing accuracy. Convoys could be rerouted around the waiting wolf packs, while Allied "Hunter-Killer" groups, equipped with escort carriers, could be sent directly to the U-boats' locations for offensive strikes.32 In one striking example from June 1943, Ultra revealed a patrol line of 17 U-boats gathering to attack shipping routes. The Allies simply diverted the convoys, and for the entire month, the U-boats made no contact, their mission a total failure.32 The ability of U-boats to sink convoy ships plummeted to almost one-sixth of previous levels after the consistent breaking of Enigma began in 1943.32

Beyond the Atlantic, Ultra provided critical intelligence for nearly every major theater of the war. For the D-Day landings in Normandy, decrypts provided detailed information on German defensive preparations and troop strength. Crucially, by breaking the ciphers of the German intelligence service, the Allies were able to confirm that their elaborate deception campaign had succeeded: Hitler was convinced the main invasion would come at the Pas de Calais and held his powerful Panzer divisions there, away from the Normandy beaches, a decision that undoubtedly ensured the success of the landings.26 From the deserts of North Africa to the final battles in Germany, Ultra gave Allied commanders an unprecedented window into the mind of the enemy, a decisive advantage that reshaped the course of modern history.

B123AAAWCAAVBSCGDLFUHZINKMOWRX

The Irony of Secrecy: State Codes and Personal Codes

The world of Bletchley Park was built on a foundation of absolute secrecy. It was a principle that governed every aspect of life at Station X, a code of silence imposed by the state to protect its most vital intelligence asset. Yet for Alan Turing, this state-mandated secrecy ran parallel to another, more personal and perilous one. The skills of discretion and coded living that he was forced to adopt as a gay man in a deeply homophobic society were ironically the very skills that made him, and others like him, such effective servants of a state that would ultimately turn on them for the secrets of their own lives.

Secrecy in War: The Official Secrets Act

Upon their arrival at Bletchley Park, every individual, from the most senior cryptanalyst to the youngest administrative clerk, was compelled to sign the Official Secrets Act.1 This was not merely a wartime precaution but a vow of silence that extended for life. The warnings were stark and unambiguous. Staff were told that any disclosure, no matter how minor, would be treated as treason, an offense punishable by a lengthy prison sentence or, as some were chillingly warned, by being shot.1

This mandate created an intensely compartmentalized culture defined by the "need-to-know" principle.7 Work was not to be discussed outside of one's immediate section, not with family, not with spouses, and not even with colleagues working in an adjacent hut.38 Veterans recall being issued cover stories to deflect probing questions from outsiders; a common one was the mundane claim of being a "confidential writer" or clerk.39 This culture of silence was so effective and deeply ingrained that it persisted for more than three decades after the war. Many who served at Bletchley took their secrets to the grave, their own families never knowing the true nature of their contribution.39 The first significant public revelations about Ultra did not emerge until the mid-1970s, long after Turing's death.5 For men like John Herivel, a key figure in an early Enigma breakthrough, this meant enduring the quiet pain of his own father dying believing his son had "never done anything" during the war.39 The state demanded a total encryption of one's professional life.

Secrecy in Self: Society's Moral "Codes"

While the state imposed a code of silence on Turing's work, it simultaneously enforced a legal and social code that demanded he remain silent about his identity. Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, Britain operated under the shadow of the 1885 Criminal Law Amendment Act. Section 11 of this act criminalized any "act of gross indecency" between men, regardless of whether it occurred in public or in the privacy of one's own home.10 The law was notoriously vague, creating a climate of fear and providing a powerful tool for extortion, earning it the moniker of the "blackmailer's charter".11

The legal framework reflected a deeply hostile social milieu. Homosexuality was widely regarded not merely as a sin but as a pathology—an "unnatural" vice, a mark of effeminate weakness, and a corrupting influence on the nation's moral fabric.11 This pervasive prejudice forced queer life into the shadows. A vibrant but clandestine subculture existed in urban centers like London, centered around private members' clubs such as the infamous Caravan Club in Soho. These spaces offered a rare sanctuary for self-expression but were also constant targets for police surveillance and raids, where personal letters and even cosmetics could be confiscated as evidence of "immoral activity".44

Survival in this environment required mastering a different kind of cryptography. Communication within the LGBTQ+ community relied on a complex system of subtle codes and shared allusions. To test the waters with a new acquaintance, one might make a veiled reference to classical figures known for same-sex relationships, like Sappho or the Emperor Hadrian and his beloved Antinous.45 In some circles, the simple act of wearing a green carnation in one's lapel—an emblem popularized by Oscar Wilde—served as a quiet declaration of identity, visible only to those who knew how to read the code.45 This was a life lived in cipher, where every interaction outside of trusted circles required a careful process of encryption and decryption to ensure personal safety.

Turing's Parallel Lives

Turing navigated these two parallel worlds of secrecy with a characteristic, and perhaps ultimately fatal, blend of discretion and frankness. Among his trusted friends and in his private correspondence, he was remarkably open about his sexuality. His 1952 letter to his friend Norman Routledge, written in the midst of his legal troubles, is a testament to this. In it, he speaks of his impending prosecution with a kind of grim, detached honesty, stating, "I've now got myself into the kind of trouble that I have always considered to be quite a possibility for me".46 There is no shame in his words, only a resigned acknowledgment of the collision between his nature and the law.

This honesty, however, appears to have been paired with a certain naivety about the workings of the world outside the realm of logic. Biographer Andrew Hodges notes that Turing seemed to possess an "out of touchness," a fundamental belief that people and systems should operate according to rational principles.47 This may explain his decision to provide the police with a voluntary and shockingly detailed five-page confession of his relationship with Arnold Murray. The officers who took his statement were astonished; he had single-handedly provided them with all the evidence needed for a successful prosecution.48 It seems Turing, who was unashamed of his actions and believed them to be morally sound, could not fully comprehend that the legal system would not share his logical assessment. He failed to see that the state's code was not based on reason, but on prejudice.

This reveals the profound and cruel hypocrisy at the heart of Turing's story. The British state demanded absolute secrecy from him to protect its own security, a task at which he excelled. It benefited enormously from the intellectual discipline and perhaps even the psychological conditioning that came from a life lived with secrets. Yet, at the same time, the state's own laws forced him into a different kind of secrecy for his own survival. The very institution that relied on his mastery of ciphers to win a war ultimately used its own rigid, irrational code to destroy him.

Prosecution and Persecution: The State Turns on Its Hero

The end of the war did not bring peace for Alan Turing. Instead, it marked the beginning of a final, tragic chapter in which the state he had served with such distinction turned the full force of its legal, medical, and security apparatus against him. His prosecution was not an isolated incident or a miscarriage of justice; it was the systematic and logical outcome of institutionalized homophobia, amplified by the paranoia of the Cold War. It was a process that methodically dismantled a national hero, stripping him of his dignity, his career, and ultimately, his life.

The 1952 "Gross Indecency" Trial: A Timeline of Destruction

The chain of events that led to Turing's downfall began with a mundane crime. In January 1952, he reported a burglary at his home in Wilmslow, Cheshire.49 The police investigation soon identified a likely connection to a 19-year-old unemployed man named Arnold Murray, with whom Turing had recently shared a brief sexual relationship.49 During questioning, Turing made a fateful decision. Whether out of a defiant sense of honesty, a logical belief that the truth was the most efficient path, or a simple miscalculation of the consequences, he did not conceal the nature of his relationship with Murray. Instead, he provided the police with a full, five-page handwritten statement detailing their sexual encounters.48 The police, who might otherwise have struggled to build a case, were reportedly astonished, later referring to it as "a lovely statement" for its prosecutorial value.48 Turing was open and unashamed, asserting to the authorities that he saw nothing wrong with his actions.52

The law, however, disagreed. In late February 1952, both Turing and Murray were arrested and charged with "gross indecency" under Section 11 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885.49 On March 31, 1952, at the Cheshire Assizes court in Knutsford, Turing, on the advice of his brother and his lawyers to avoid the public humiliation and certain conviction of a trial, pleaded guilty to the charges.48

Mandatory Hormone "Treatment": Chemical Castration

The court presented Turing with a barbaric choice: a prison sentence or two years of probation. The probation, however, came with a devastating condition: he had to submit to one year of "organo-therapy".55 This was a clinical euphemism for chemical castration, a medical procedure designed to "cure" his homosexuality by suppressing his libido.53

The "treatment" consisted of regular injections of stilboestrol, a synthetic estrogen hormone.58 This was not medicine; it was a form of physical and psychological torture rooted in the pseudoscientific belief that homosexuality was a biological malady that could be corrected by altering a man's hormonal balance.58 The effects on Turing were profound and devastating. Physically, the injections rendered him impotent and caused gynecomastia, the development of breast tissue, which he reportedly tried to hide with a specially made vest.52 The psychological toll was equally, if not more, severe. The humiliation of the procedure, combined with the forced alteration of his body, inflicted immense emotional distress and undoubtedly contributed to a deep depression.58 In a poignant letter to a friend, he wrote of the therapy with a chillingly detached tone: "It is supposed to reduce sexual urge whilst it goes on... I hope they're right".55

Consequences: Professional and Social Ostracization

The conviction and subsequent "treatment" were only the beginning of Turing's public and professional ruin. In the tense, paranoid atmosphere of the early Cold War, homosexuals were widely regarded by Western intelligence agencies as inherent security risks. The prevailing logic was that their "secret life" made them uniquely vulnerable to blackmail by Soviet agents, who could threaten to expose them.60

As a result of his conviction, Turing's security clearance was immediately and permanently revoked.50 This single act severed his connection to the world of cryptography he had helped to create. He was barred from continuing his crucial consulting work for the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), the postwar successor to Bletchley Park, and was forbidden from ever entering the United States.53 This effectively exiled him from the international scientific community, cutting him off from his American colleagues at a time when the field of computing, which he had pioneered, was rapidly advancing. The man who had been one of Britain's greatest strategic assets during the war was now officially branded a threat to its national security.

The state's persecution of Alan Turing was a coordinated assault from all its pillars of power. The legal system provided the instrument of conviction, the medical establishment provided the tool of physical punishment disguised as therapy, and the national security apparatus provided the means of professional annihilation. It was a clear demonstration of how institutionalized prejudice can transform a nation's most brilliant mind into a pariah, systematically unmaking the very hero it should have celebrated.

Collision of Triumph and Tragedy: A Legacy in Cipher

For decades after his death, Alan Turing's legacy remained as encrypted as the German codes he had once broken. The public narrative was one of shame—a convicted criminal who had taken his own life. The truth of his triumph, a state secret locked away by the same government that had persecuted him, would only emerge slowly, forcing a painful and incomplete reconciliation between the two irreconcilable halves of his story. The long journey toward a posthumous pardon revealed not only the depth of the injustice done to Turing but also the profound limitations of state mechanisms in atoning for historical wrongs.

Public vs. Private Legacy: The Decades of Silence

In the years following his death on June 7, 1954, Alan Turing was remembered, if at all, for the scandal of his 1952 conviction. His monumental contributions to the Allied victory in World War II were shrouded in secrecy, bound by the Official Secrets Act and the UK's "thirty-year rule," which kept government records classified for decades.5 His colleagues from Bletchley Park remained silent, and Churchill's histories of the war made no mention of Ultra. The man who had shortened the war by years and saved millions of lives was erased from the official history he had helped to write.

The first crack in this wall of silence appeared in 1974 with the publication of The Ultra Secret by former RAF officer and Bletchley Park veteran F. W. Winterbotham.5 This book offered the first popular account of the codebreaking operation, finally revealing the existence of Ultra to a stunned public. However, it was not until the release of further documents and the publication of Andrew Hodges' seminal 1983 biography,

Alan Turing: The Enigma, that the full extent of Turing's central role became clear.47 The full story, in fact, was not widely understood until the 1990s.34 This gradual unveiling created a profound historical dissonance, forcing society to grapple with the image of a national savior who had been treated as a pariah.

The Long Road to Recognition and the Politics of a Pardon

As public awareness of this gross injustice grew, a powerful campaign emerged to demand official recognition and redress for Turing. Spearheaded by figures like Manchester politician John Leech and supported by leading scientists such as Stephen Hawking, the movement gained unstoppable momentum.64 In 2009, Prime Minister Gordon Brown issued a formal, unequivocal apology on behalf of the British government for the "appalling" way Turing had been treated, acknowledging that a hero "deserved better".51

The campaign culminated on December 24, 2013, when Queen Elizabeth II granted Alan Turing a posthumous Royal Prerogative of Mercy, a full pardon for his conviction.64 While celebrated as a landmark victory, the act of the pardon was itself fraught with controversy and complexity. Critics, including Turing's biographer Andrew Hodges, pointed out a fundamental flaw in the logic: a pardon is an act of forgiveness for a crime committed, which inherently implies that the recipient was guilty of a wrongdoing.66 This perspective was echoed by other men who had been convicted under the same discriminatory laws. As one victim powerfully stated, "To accept a pardon means you accept that you were guilty. I was not guilty of anything".68

The core of the issue was that Turing was not a man wrongfully convicted under a just law; he was a man rightfully convicted under a profoundly unjust law.67 The injustice lay not in the court's verdict but in the very existence of the statute that criminalized his identity. To "pardon" him was, for some, an insult—an act of mercy from the very institution that should have been begging for his forgiveness. This debate highlighted the inadequacy of existing legal tools to address historical moral failures. The state's mechanisms are designed to correct violations of its laws, not to condemn the laws themselves. Nevertheless, the momentum from Turing's case led to the Policing and Crime Act 2017, informally known as the "Alan Turing Law," which issued a blanket posthumous pardon to an estimated 49,000 other men who, like Turing, had been convicted for consensual homosexual acts that are no longer considered crimes.56

Quotes: The Voice of the Persecuted

In the midst of his persecution, before the trial that would seal his fate, Turing wrote a letter to his friend and fellow mathematician, Norman Routledge. This letter remains one of the most vital and heartbreaking documents of his life, offering a direct window into his mind as he faced his own destruction. His words reveal a man grappling with his fate with a mixture of detached analysis, dark humor, and devastating clarity.46

On his long-held awareness of his vulnerability, he wrote with chilling prescience:

"I've now got myself into the kind of trouble that I have always considered to be quite a possibility for me, though I have usually rated it at about 10:1 against."

Even as his world was collapsing, his analytical mind continued to frame his own tragedy as a story, a problem to be dissected:

"The story of how it all came to be found out is a long and fascinating one, which I shall have to make into a short story one day, but haven't the time to tell you now."

He foresaw the transformative, dehumanizing power of the impending "treatment" with haunting foresight:

"No doubt I shall emerge from it all a different man, but quite who I've not found out."

Most profoundly, he articulated the deep fear that his identity would be used as a weapon to illogically discredit his life's work. He saw with perfect clarity how prejudice would poison the public's perception of his science:

"I'm afraid that the following syllogism may be used by some in the future. Turing believes machines think. Turing lies with men. Therefore machines do not think." 46

This final, devastating syllogism was not just a prediction; it was a decryption of the irrational code of bigotry. He understood that in the court of public opinion, his personal life would be used to invalidate his intellectual legacy. He was right. For decades, it did.

Encryption as Identity: The Modern Resonance

The metaphor of encryption in Alan Turing's life extends far beyond the German ciphers he broke. His personal struggle with secrecy resonates with a long history of LGBTQ+ communities developing their own coded systems for survival. Today, this metaphor finds a powerful and urgent new meaning in the global debate over digital privacy. The fight for strong, unbreakable digital encryption is, in essence, the modern frontier of the same battle for personal autonomy and the right to a private sphere that defined Turing's era.

Metaphor Extension: From State Ciphers to Personal Survival

Long before the advent of digital cryptography, marginalized communities, particularly LGBTQ+ people, were masters of a different kind of encryption. In a world where their identities were criminalized and their love was a prosecutable offense, survival depended on the ability to hide in plain sight. This was achieved through a rich tapestry of codes, symbols, and subtexts that allowed them to communicate, find one another, and build communities under the radar of a hostile society.71

This "social encryption" took many forms. In Britain, some gay subcultures used Polari, a unique form of cant slang, to converse without being understood by outsiders. More widespread was the use of subtle symbolism and allusion. The practice of floriography, or the language of flowers, was adapted for queer signaling; in the late 19th century, Oscar Wilde and his circle popularized the wearing of an artificially dyed green carnation as a discreet emblem of "unnatural" desire.45 Similarly, conversations could be seeded with allusions to historical or literary figures known for same-sex love, a way of "testing the waters" to see if an acquaintance was also "in the know".45 These codes were not a game; they were a necessary shield, a form of personal encryption deployed against a world that sought to decrypt and punish their private lives.

Modern Parallels: Digital Privacy and Human Dignity

Today, this historical need for a protective shield has found a direct technological successor in digital encryption. For millions of LGBTQ+ individuals living in the more than 60 countries where their identity is still criminalized—and where punishments can range from imprisonment to death—secure, end-to-end encrypted communication is not a luxury but a lifeline.71 Encrypted messaging platforms and services provide a vital safe haven, allowing people to explore their identities, seek support, access life-saving healthcare information, and organize for their fundamental human rights without the constant fear of surveillance, exposure, and persecution.74 As Shae Gardner of the advocacy group LGBT Tech states, "In the 70+ countries where being LGBTQ+ is still criminalised, encryption can be a matter of survival".71

This makes the ongoing global debate over encryption all the more critical. Governments, including in Western democracies like the United Kingdom, have increasingly pushed for legislation that would weaken encryption or mandate "exceptional access" or "backdoors" for law enforcement, often under the banner of public safety.74 However, as digital rights organizations like the Open Rights Group and the Electronic Frontier Foundation have consistently argued, this is a dangerous fallacy. A backdoor created for the "good guys" is a vulnerability that can be exploited by anyone—malicious hackers, foreign intelligence services, and, most critically, oppressive regimes seeking to hunt down dissidents and minorities.71 For an LGBTQ+ activist in a country with anti-gay laws, a compromised encryption standard is not an abstract technical issue; it is a direct threat to their life.

In a fascinating turn of the metaphor, modern cryptography is also exploring the concept of identity-based encryption (IBE), where a person's public identifier, such as an email address, can function directly as their public key, simplifying the process of secure communication.77 This presents a powerful modern inversion of Turing's predicament. Whereas his identity was a liability that had to be hidden and encrypted, modern cryptography envisions a world where one's public identity can be the very foundation of security and trust.

Reader Engagement: Decrypting the Present

To fully understand the legacy of Alan Turing is to decrypt the subtext of his story and apply it to the present. The historical battle he faced was over the right to a private life, free from state intrusion into the most personal aspects of his identity. Today, that same battle is being waged on a new technological front. The struggle over encryption is a direct philosophical successor to the 20th-century fight for LGBTQ+ rights. Both are fundamentally about the right to a private sphere and the right to self-definition without fear.

When governments debate laws like the UK's Online Safety Act or propose measures that would undermine end-to-end encryption, they are not merely discussing technical standards. They are debating the extent to which the state has the right to access the private lives of its citizens. For those in the LGBTQ+ community, the historical memory of how the state has used such access as a tool of oppression is still painfully fresh. The justification of "public safety" or "preventing crime" is the same rationale that was used to enforce the moral codes that destroyed Alan Turing. The fight for strong, unbreakable encryption is therefore not just a niche issue for tech experts; it is a fundamental human rights issue. It is the modern embodiment of the struggle for privacy, dignity, and survival that defined Turing's tragic life.

Epilogue & Call to Action: Unmasking Injustice

The story of Alan Turing is the ultimate tragedy of secrets. He was the man who decoded the most complex secrets of a hostile state, only to be destroyed by the intolerant secrets of his own. He was a hero of the mind, celebrated in the shadows for saving a nation, yet publicly persecuted and haunted by the very concept of secrecy he had mastered for the benefit of all. His legacy is a testament to the monumental triumphs the human intellect can achieve and a harrowing reminder of the devastating toll of prejudice. To truly honor him, we must do more than erect statues or place his face on currency. We must commit to dismantling the very systems of injustice and intolerance that led to his ruin. Honoring Turing demands concrete action.

A Harder Call to Action: A Framework for True Atonement

A genuine tribute to Alan Turing requires moving beyond symbolic gestures and engaging in a sustained, multi-pronged effort to address the echoes of his persecution that still reverberate around the world. This framework for atonement is built on four pillars: legal reform, institutional accountability, comprehensive education, and ongoing vigilance.

Legal Reform: Repeal All "Turing Laws" Worldwide

The persecution that ended Turing's life was not an anomaly; it was the law. Today, that legal reality persists for millions. As of 2024, at least 62 countries continue to criminalize consensual same-sex relations.73 The punishments are draconian, ranging from imprisonment to death. Recent years have seen horrifying regressions, not progress. In May 2023, Uganda enacted a new Anti-Homosexuality Act, which includes life imprisonment for same-sex relations and the death penalty for so-called "aggravated homosexuality".72 These laws are the direct descendants of the statutes that condemned Turing.

Action: A global coalition of governments, human rights organizations, and citizens must exert sustained diplomatic and economic pressure on nations that maintain these laws. This includes targeted sanctions, conditioning foreign aid on human rights progress, and providing robust support for local activists fighting for decriminalization on the ground.

Institutional Accountability: Apologize and Expunge

Symbolic pardons are insufficient when the underlying law was the source of the injustice. A true act of institutional accountability requires states to formally acknowledge their role as persecutors. There is precedent for this. In 2018, German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier issued a formal apology and asked for forgiveness for the historical persecution of gay men under the infamous Paragraph 175, acknowledging the suffering inflicted both during and after the Nazi era.82

Action: All governments that historically criminalized LGBTQ+ identities must issue formal, unequivocal apologies. These should not be "pardons," which imply the victim was guilty, but clear condemnations of the unjust laws themselves. Furthermore, all historical convictions for consensual same-sex acts must be formally and automatically expunged from all records, cleansing the stain of criminality from the victims and their families.

Education: Teach the Whole Story

The popular narrative of Alan Turing is often sanitized. He is celebrated as the codebreaking genius and the father of computing, while the brutal details of his persecution are glossed over or omitted entirely. This incomplete story robs his life of its most powerful and urgent lessons.

Action: Educational curricula must be reformed to integrate Turing's full, unvarnished story. Students should learn about the Enigma machine and the universal Turing machine, but they must also learn about the 1885 Criminal Law Amendment Act, the practice of chemical castration, and the pervasive societal homophobia that led to his death. Only by teaching the whole story can we equip future generations with a true understanding of the devastating real-world consequences of prejudice and the importance of defending the rights of all individuals.

Ongoing Vigilance: Defend Digital and Personal Freedoms

The battle for the right to a private sphere, which was at the heart of Turing's struggle, is now being fought on the digital frontier. The fight for strong encryption is inextricably linked to the fight for LGBTQ+ rights and the protection of all marginalized communities.

Action: We must provide active and vocal support for the organizations that operate at this critical intersection. This includes digital rights champions like the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) and the Open Rights Group (ORG), who lead the fight against government surveillance and anti-encryption legislation.71 It also includes LGBTQ+ advocacy groups that have developed crucial expertise in digital safety and privacy, such as

LGBT Tech, GLAAD, and the National Center for LGBTQ Rights (NCLR).75 Supporting these organizations with time, attention, and resources is the most direct way to apply the lessons of Alan Turing's life to the defining civil liberties challenges of our time.

Let us honor Turing not only by decoding ciphers, but by unmasking injustice.

"Sometimes it is the people no one imagines anything of who do the things that no one can imagine."

— Alan Turing

“If I ever cross your mind, however brief, I hope it’s with a passing that lightens your heart with a benevolent smile.

And if not, forgive me.”

—

Work Cited:

https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/alan-turing-betchley-park

https://www.google.com/culturalinstitute/exhibit/bletchley-park-home-of-the-codebreakers/wRANFg9s

https://u.osu.edu/wwiihistorytour/2016/05/17/the-impact-of-bletchley-park/

https://www.exploringsurreyspast.org.uk/themes/subjects/diversity/lgbt-history/qs/

https://textbooks.cs.ksu.edu/cc110/iii-topics/16-cryptography/04-enigma/

https://www.ciphermachinesandcryptology.com/en/enigmatech.htm

https://uregina.ca/~kozdron/Teaching/Cornell/135Summer06/Handouts/enigma.pdf

https://www.bletchleypark.org.uk/our-story/6-facts-about-the-bombe/

https://ethw.org/Milestones:Code-breaking_at_Bletchley_Park_during_World_War_II,_1939-1945

https://cstheory.stackexchange.com/questions/11797/alan-turings-contributions-to-computer-science

https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1283&context=younghistorians

https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/how-alan-turing-cracked-the-enigma-code

https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1283&context=younghistorians

https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/how-alan-turing-cracked-the-enigma-code

https://ethw.org/Milestones:Code-breaking_at_Bletchley_Park_during_World_War_II,_1939-1945

https://briacommunities.ca/blogs/peg-buchanan-bletchley-park-codebreaker/

https://www.usni.org/magazines/naval-history-magazine/1997/december/secret-bletchley-park

https://www.exploringsurreyspast.org.uk/themes/people/scientists/alan_turing/

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00918369.2022.2131131

https://media.nationalarchives.gov.uk/index.php/lgbt-love-letter/

https://www.oxfordstudent.com/2019/02/14/an-enigma-the-role-of-codes-in-the-lgbtq-community/

https://lettersofnote.com/2012/06/23/yours-in-distress-alan/

https://bobonbooks.com/2022/08/29/review-alan-turing-the-enigma/

https://www.newstatesman.com/science-tech/2013/07/putting-right-wrong-done-alan-turing

https://studentsforliberty.org/blog/alan-turing-irrational-persecution/

https://www.cia.gov/stories/story/the-enigma-of-alan-turing/

https://www.exploringsurreyspast.org.uk/themes/people/scientists/alan_turing/

https://lgbtlawyers.co.uk/2021/01/29/alan-turing-and-his-fascinating-legacy/

https://studentsforliberty.org/blog/alan-turing-irrational-persecution/

https://www.mazzonicenter.org/news/alan-turing-against-all-odds

https://www.petertatchellfoundation.org/alan-turing-the-medical-abuse-of-gay-men/

https://www.reddit.com/r/AskHistorians/comments/1zw3wv/what_was_life_like_in_1940s_britain_for_lgbt/

https://www.reddit.com/r/AskHistorians/comments/1zw3wv/what_was_life_like_in_1940s_britain_for_lgbt/

https://www.glsen.org/sites/default/files/Alan%20Turing%20True%20to%20Himself-Final.pdf

https://www.aps.org/publications/apsnews/201401/physicshistory.cfm

https://www.gov.uk/government/news/royal-pardon-for-ww2-code-breaker-dr-alan-turing

https://blog.sciencemuseum.org.uk/alan-turing-granted-royal-pardon/

https://abovethelaw.com/2013/12/the-mistake-behind-the-posthumous-pardon-of-alan-turing/

https://www.slaw.ca/2016/10/28/the-alan-turing-law-whos-pardoning-whom/

https://educationhub.blog.gov.uk/2021/02/lgbt-history-month-alan-turing-and-his-enduring-legacy/

https://www.openrightsgroup.org/blog/queercryption-safety-in-numbers/

https://www.lgbthero.org.uk/which-countries-criminalise-homosexuality

https://www.humandignitytrust.org/lgbt-the-law/map-of-criminalisation/

https://www.lgbttech.org/post/the-importance-of-encryption-for-the-lgbtq-community

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2024/07/beyond-pride-month-protecting-digital-identities-lgbtq-people

https://cpl.thalesgroup.com/blog/access-management/identity-based-cryptography

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Capital_punishment_for_homosexuality

https://www.genocidewatch.com/single-post/lgbtqi-persecution-the-global-genocide-of-gay-people

https://www.nclrights.org/